…and motion matched with motion, song with song–

a song that, sung by those sweet instruments,

surpasses so our Muses and our Sirens

as firstlight does the light that is reflected.

– Dante Alighieri, “Paradiso,” XII (6-9)

“…the melody which, at intervals unequal, yet differing in exact proportions, is made by the impulse and motion of the spheres themselves, which, softening shriller by deeper tones, produce a diversity of regular harmonies.”

– Cicero, “The Dream of Scipio”

Stepping into the Houston Center for Contemporary Craft, the visitor hears tones from Andy Paiko and Ethan Rose’s Transference long before arriving in the gallery, but because the range of frequencies these sounds inhabit cannot be located in space by the human ear, the listener cannot discern from whence the sound originates. “Ethereal,” “otherworldly,” “transparent” and “pure” have all been used to describe the apparently sourceless, surrounding sound which seemingly materializes spontaneously from thin air. The sound might be compared to the spooky sound of a theremin or a musical saw, but anybody who has rubbed a wet fingertip around the edge of a wine glass knows this phenomenon. This is the sound of glass, singing.

“It’s quieter today,” says Susie Silbert, curatorial fellow at HCCC. “It changes with the weather.”

Silbert takes a break from office work to re-wet the fabric tips which meet the glass to create the sound, and while doing so, explains the mechanics and theory behind the instillation. What, after all, is a “kinetic sound installation” doing in a crafts museum?

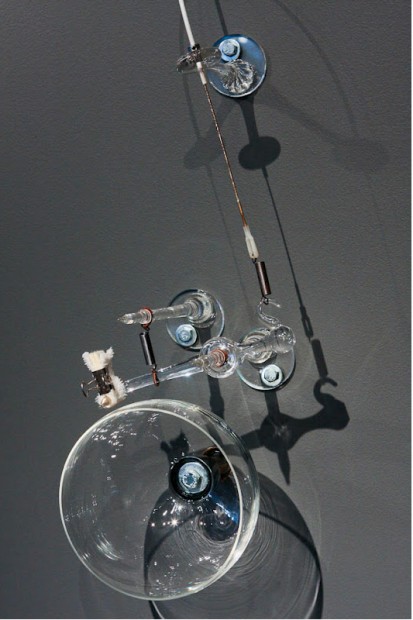

In the gallery, dozens of handmade glass “bowls” of varying sizes are mounted on three walls and four pedestals, spinning at a uniform, constant speed. Alongside these bowls, also mounted on the walls and pedestals, are the also handmade glass levers and mechanisms which bear the springs and tension wires that engage and disengage the fabric tips Silbert is now rewetting. Invisible to the viewer, inside the walls and pedestals, are the gears and motors that drive this sound machine, as well as the computer program that controls it all.

“Glass is a liminal substance,” Silbert continues. “It is there, it marks a boundary, but like sound—which is just the vibration of air particles—it is transparent. Both sound and glass are invisible—present, but also not present.”

Paiko and Rose, she explains, have found a way to activate the invisible air contained within the void of these glass vessels to produce a discernable yet elusive harmony. Perhaps this is the thought behind the piece’s title, Transference—transferring friction on transparent glass into the invisible ether—the interplay between substance and void.

Still, though, composed almost entirely of unadorned, clear glass, the piece is not without its visual delights, and the intersection between sight and sound results in a sort of synesthesia. As the disembodied sounds swirl about the viewer’s head, larger bowls can be seen undulating as they resonate; shadows of clear glass converge with one another to create overlapping Venn Diagrams on the gallery walls; playful accents can be seen hidden in the “glass icicle” mounting hardware (which are deliberately evocative of the kitschy Christmas ornaments that are an almost universally-hated source of many a glass-maker’s income); and on close view, distorted reflections and rainbow starburst highlights sparkle back at the viewer from overhead track lights.

Portland, OR-based composer Ethan Rose claims an interest in obsolete instruments and views this work as a reinterpretation of Benjamin Franklin’s “glass armonica,” which consists of glass bowls mounted on a spinning rod that are played with a musician’s wet fingertips. (For a contemporary description of the glass armonica’s sound, check out this poem by Nathaniel Evans.)

To this viewer, however, the sounds produced by Transference are much more reminiscent of Brian Eno’s seminal album, “Ambient 1: Music for Airports,” in particular its final composition “2/2.” Though the resulting sound is so similar, Rose arrives at this sound through very different means from Eno: Eno used one of the earliest synthesizers; Rose collaborates with glass artist Andy Paiko, who distinguishes himself from most other glass artists by making functional (rather than decorative) glass vessels. (He has previously made a glass chair, a glass spinning wheel and glass bicycles.)

“It literally and figuratively turns the idea of a vessel on its side,” Paiko says in a video about the piece. “These are technically vessels, but in this case this vessel contains nothing but air; in this case the vessel is not as much about containing something as it is about pushing something out.”

Silbert wraps up by explaining the mechanics of the piece. Hidden in the walls are the chain motors that drive the vessels’ rotation, which are sound-insulated to minimize noise that would distract from the ethereal tones. Also hidden within are the spring-loaded mechanisms which engage and disengage the levers bearing the wet fabric tips. The levers are controlled by a computer program which operates them randomly, so that any given combination of tones never repeats.

This brings me to the title of this review and the concept of “the music of the spheres.” In medieval music theory, there are three classes of music: musica instrumentalis (“instrumental music,” played on instruments, i.e. our contemporary understanding of “music”), musica humana (“human music,” the extant harmony between the human body’s systems of tissues and organs) and musica mundana (“worldly music,” the music of the world; the harmony between planets and the stars, the seasons and the elements).

As Silbert explains that Paiko and Rose, in their quest to eliminate extraneous noise, finally settled on motors from kidney dialysis machines (which are made to operate quietly so dialysis patients may sleep through the night), it occurs to me that in Transference they have—like the Venn-diagram-like converging shadows of clear glass on the gallery walls—achieved a synthesis of all three medieval classes of music. The vessels, as a variation on Franklin’s glass armonica, are by no stretch stretch of the imagination a clear example of “musica instrumentalis,” their use of kidney dialysis motors shifts the piece into the territory of “musica humanis,” and having read descriptions of “musica mundana,” i.e. “the music of the heavenly spheres,” in Dante’s “Paradiso“ and Cicero’s “The Dream of Scipio,” this is precisely how any reader would expect it to sound—as evidenced by reviewers’ repeated use of words like “celestial” and “ethereal” as descriptors.

Though Paiko and Rose have succeeded in quieting much of the machine sound, their efforts are not perfect, and as Silbert notes, the piece sounds different from day to day. On a subsequent visit, I am glad to hear snatches of the mechanics behind the disembodied ethereal tones; it’s like hearing whirrs, pops and crackles while listening to 45s on an old jukebox. But by removing the player and mechanizing their glass armonica, Paiko and Rose provide the perfect segue into the larger gallery at HCCC, where textile artist Lia Cook shows tapestries depicting photographs made on a digital Jacquard loom, which is an update of the punch-card looms of the Industrial Revolution, remembered as being among the first digital machines.

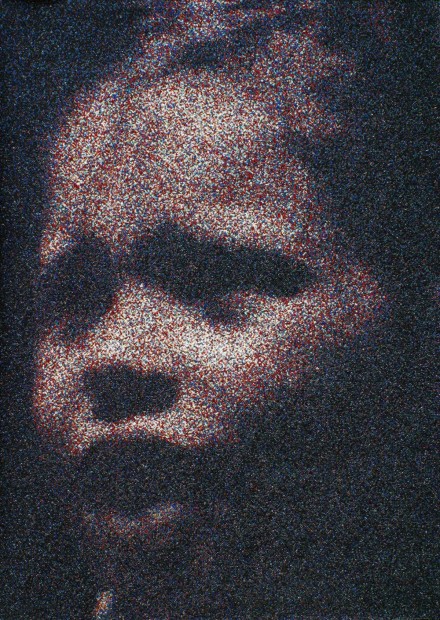

Taken on their own, Cook’s images are not all that memorable—they seem like they might have come from any stock photo website—but rendered in such a large format and processed through the loom, they take on a fragmented, pixilated, pointillistic quality when viewed up close. They resemble the mazes of a Pac-Man game. The more interesting images in the series depict Cook’s collaboration with neuroscientists who help her map viewers’ brain activity as they gaze upon her images. She then renders this brain activity and overlays it upon an image of said viewer apprehending said image, as in the piece Facing Maze.

Like the Persian rug-maker who, by convention, introduces one deliberate flaw into her design so as not to strive for perfection, which falls within the exclusive purview of god, Cook uses computer-aided design to make each photographic reproduction unique. Given this, combined with the sounds of Transference filling the space, moving about this gallery the viewer is still unable to shake the feeling of a different plane of existence. This and Cook’s interest in memory then calls to mind Japanese filmmaker Hirokazu Koreeda’s 1998 film “After Life,” which depicts a purgatory-like place where the recently deceased must choose one memory from their life which their soul will inhabit for all eternity. What kind of brain activity would be engendered by gazing upon a single image for all eternity? Would the brain not also be frozen? These are the types of questions that arise in this viewer’s brain while strolling about Cook’s images with Rose and Paiko’s celestial soundtrack playing in the background, and the viewer is delighted to note that after exiting through the gallery containing Transference, stepping out into the parking lot behind HCCC, the notes continue to resonate for a moment in the silence.

Transference: Andy Paiko & Ethan Rose

Bridge 11: Lia Cook

Houston Center for Contemporary Craft

February 4 – May 13, 2012

______________

Harbeer Sandhu is a fiction writer and poet who lives in Houston.