Lucky has been anything but. A 46-year resident of the San Antonio Zoo, the sixtyish, female elephant became a cause célèbre for animal rights activists after her longtime companion Alport died in 2007, leaving Lucky alone. Since then, she’s gained a new friend, Boo, but Lucky remains, as she has been since she was captured at age 4 in her native Thailand, a prisoner of man. The zoo refused to send her to an elephant sanctuary in Tennessee where she could have had much more room to roam free like she was born to do.

But it was reading “Water for Elephants” that led San Antonio artist Michele Monseau to use Lucky as the model for her video installation, “Elephant in the Room,” through Nov. 7 at Unit B. Her video captures some of Lucky’s most disturbing behavior, repetitive swaying and head-bobbing, which indicate psychological distress. However, Monseau’s drawings and miniature vinyl elephant silhouettes have a playful quality reflecting the childhood wonder of seeing an elephant up close in a zoo for the first time.

And that’s the trouble with zoos, because it’s hard to abhor something that you enjoyed so much as a child. Besides the chance to see animals in a way no documentary can match, zoos also do important animal research and help to preserve species. Monseau says her exhibit is not intended to make a political statement, though she makes a poignant, humanistic one.

“Elephant in the room is about reverence, melancholy, celebration, and feedback loops,” Monseau says. “The mind and the spirit come up with ways to fill empty space when any living creature is deprived of the natural feeding of its soul. Rhythm is primal, and comfort. Repetition is circular.”

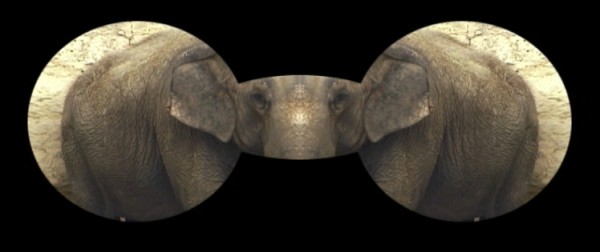

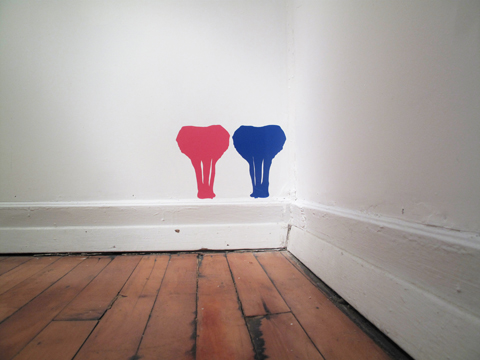

Monseau is known for her use of mirror images in video, such as “swingsong (purplerain)” at the McNay Art Museum, which animated mirror images of a lake and mountain to rock perspective. Lucky’s swaying is exaggerated in mirror images outlined by binoculars. A flashlight on the floor lights up a pair of elephant silhouettes tucked into a corner, alluding to poachers hunting elephants at night.

For a soundtrack, Monseau softly talks on a feedback loop, like a troubled person repeating an imaginary conversation they would like to have with an important someone. But at one point, an elephant sounds like the trumpet of fate.

In her circular, framed drawings, she focuses on details of the elephant, such as the giant, wrinkled elephant eye staring out of “TV Eye.” The trunk forms a spiral in “Curl” and two elephants nuzzle “In the Ring.” But there’s no elephant in a drawing of the fried dough treat known as an “elephant ear.” Monseau shows how the blind men in the Indian fable could have been confused, while raising the question they were trying to answer: What is the nature of this beast?