DiverseWorks‘ State Fair feels like a version of “Now THAT’S What I Call Social Practice!” As you walk through, you are beckoned to participate in an idea barter booth, to ask an artist about his role as a shrimp salesman, to chat with a gossip swapper, to play a carnival game with candlemakers, to read accumulated stories from a popcorn giver and to hear your cell phone’s future from a fortune teller. Your arms are laden with stuff by this point, but it is not until the very end, when you reach an austere white booth labeled “Performance Prescriptions,” that you have a truly generous experience. You have arrived at the clinic-come-drama-therapy office of Autumn Knight.

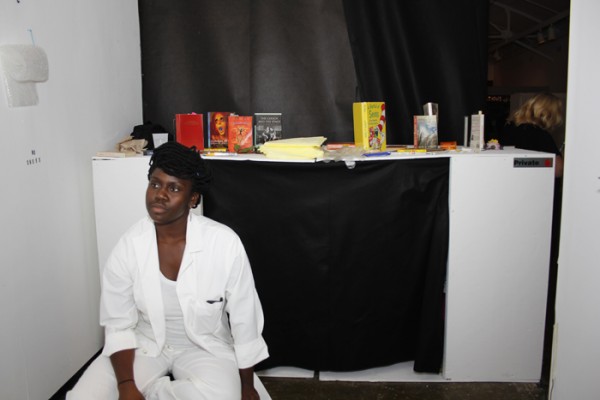

From bowing and squinting under the intake window to sitting in the “waiting area” with magazines and expectations, this booth recreates the experience of visiting an office to find out what is wrong with you and get fixed. Only after completing your paperwork and waiting your turn for a strictly one-on-one appointment do you meet the calming, white coat-clad Dr. Knight, who manages to be sincere as a person even while pantomiming a doctor through the role of an artist.

This is what happened to me next:

From my answers on the intake form, Dr. Knight asked me about my Diet Coke addiction, the loss of my mom and my “unacknowledged feelings” of having a HUGE crush on an unnamed boy. In the end, we decided that this last matter was my chief complaint and so this regimen was prescribed:

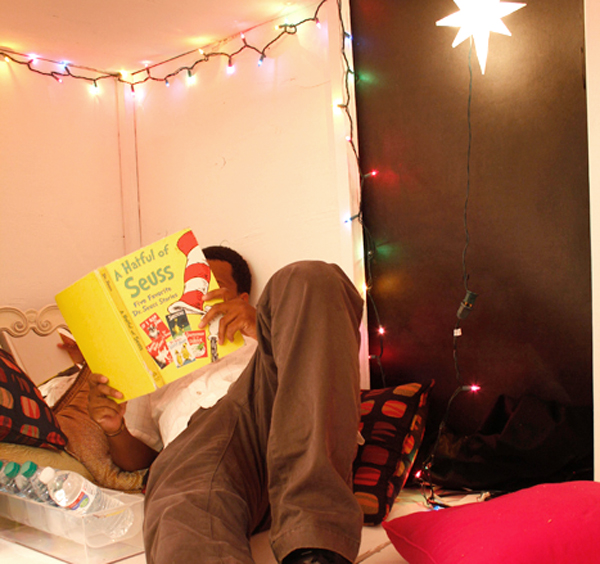

1. Go into the “Interpersonal Space Station” (a cozy sitting space that reminded me of my childhood clubhouses with Christmas lights, free bottled water and pillows).

2. Write a song for my crush (“I looked you up on Google and I think you’re so cute…”).

3. Sing it (I don’t sing).

4. Out loud (Aah!).

5. In front of others (AAAAHH!).

6. To the nearest guy who looked like my description of my crush.

7. While he stood on a pedestal as I blushed uncontrollably, mumbling my song and handing him a rose.

This was mortifying, but I suppose also cathartic. I certainly felt better after doing it than I felt while doing it.

As fun as that was, my mind’s wheels were still turning as I pondered the role of the artist as expert, the audience as client, the economy of exchange, and the ethics of participation and social practice. Knight’s approach became even more fascinating when my roommate Indre went in. Indre’s prescription was to perform Knight’s role of the doctor for the next visitor. It was about suspending self-analysis and actively listening to others.

Knight has a masters in drama therapy from NYU and is interested in the economy of giving things away for free. Her other works have given away “Advice or Books” at Hermann Park and free massages in exchange for actions such as “call your mother right now” and “run around the block.”

Throughout the performance, Knight has been surprised by how candid people are willing to be. On her part, she has been freed up to perform a more fluid and liminal role as a performance artist than would ever be sanctioned as a drama therapist.

Knight struck a balance between critique of the diagnostic and clinical heavy-handedness of her education and the mimicking of it to her benefit. While Knight’s prescriptions included experiencing her work, they also included her experiencing your inner business. People love to talk about themselves.

Also, Knight only gave out performance as a prescription, not the medicine itself. I’m beholden to art that works as a catharsis, and I think Knight’s work stands out because amongst all of State Fair’s freebies, her gift required and benefited from the participant’s ownership.

What do I mean? I’ve had a beef with this Clifford Owens‘s performance at the CAMH for a long time now. He essentially enlists the audience as material for staged photographs of them performing actions which he incites. He has them behave in a way that he describes as cathartic, and that most everyone who came out door described as amazing.

However, people also came out of the space weaving analyses around one guy, and remembering a woman who was ashamed of her participation. Most of all, amidst the talk of the role of photography in performance art, Owens fails/denies to address the role of authority in his work, or his role of puppeteer as part of the work. My memory of that night includes Owens choosing questions (“Are you a gay man?”) and suggesting actions (“Take off your clothes”) that took advantage of the audience, instead of giving them an advantageous experience.

I don’t think performance art needs to be kind or gentle. Works like Santiago Sierra’s (tattooing a straight black line across the backs of hired day laborers) or Gim Hong-Sok’s (installation in the “Your Bright Future” exhibition of supposed families of illegal immigrant day laborers, paid below minimum wage, holding 8-hour poses in animal costumes for museum visitors) are incredibly powerful in addressing their own manipulation and structures of power.

But Owen’s work had neither of these, it just had a bunch of folks who came to the institution, were controlled by the expert and left nodding their heads in agreement. It’s too eerily familiar to the Stanford Prison Experiment or a fundamental cult, if you ask me.

So back to Knight, who, in contrast, is mindful of “the art artifice versus real confession” and “determining the appropriate leap for each individual.” Her master’s thesis involved testing out which aspects of performance art as rituals of growth and rites of passage are actually cathartic.

She thinks about the availability of therapy to people and whether or not we do things that are therapeutic. She insists on giving individual attention to each participant. When I say the work is original I mean that it comes from the origin of art as a validating and transcending expression of human experience.

Art has a long tradition of exemplifying the psychological underpinnings of an individual, time, or culture. Artists are just in touch enough with the crazy to excise it. Knight nods to the set-up-shop pseudoscientific, confessional, counselor, researcher-in-white-coat trends in participatory work, but the intersections of authorship and collaboration in “Performance Prescriptions” are much more complex and compelling.

For one thing, she gives each person “a short but complete experience” without categorizing them in the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). She determines a tailored but non-condescending action for them to perform. And unlike the Marina Abramović piece Knight and I discussed, The Artist is Present at MOMA (in which Abramović sat silently in a chair across from one museum visitor at a time for all hours and days on end), Knight wants to know “can we move into another moment where the artist is present AND…”

AND is the part where language and life experience are exchanged. It’s where the artist listens to the audience and creates something from this listening as an improvisational practice, meant both to transform themselves and offer a small, psychological untangle to the participant.

Knight strikes an interesting dynamic by being the conceiver of, but not the performer of the action. She is a conduit for the participant’s divulged behavioral information, while she simultaneously makes the participant a conduit for her idea.

She doesn’t deny authorship to be an ethical art martyr, but she stops short of exploiting her audience as material. Knight is influenced by Yoko Ono’s Instruction Paintings, William Pope.L, Alison Knowles and Adrian Piper. But as far as where this work falls on the spectrum of performance art and social practice, Knight says, “You’ve either got to really give them a show, or make sure that they are really getting something from it.”

Carrie Schneider is a conceptual artist who sees artists as activators, free agents, problem solvers, tricksters, healers, liminal space dwellers and conduits for change. Her work includes collaborating in the development of labotanica, facilitating art projects for refugee youth from Burma, and launching an online library of public-generated audio walking tours around Houston.

1 comment

While Owens work isn’t unproblematic, staged photos lead to the creation of an artwork that doesn’t pretend to be anything but. I wasn’t at the State Fair so I can’t comment directly on the work at hand, but too much of this work gets too far away from an art experience but not far enough into actual, valuable social work to make an impact in that realm.

Social work is a noble profession and people devote their lives to it without presenting it as an “artwork” or seeking any kind of wider “fame” for it. Too often the kind of work described above seems like an insult to real social workers and comes off as self-hatred (over being an artist who makes useless objects).

I am into art that fuctions outside the artworld, but Beuys’ “7000 Oaks” isn’t a scultpure without the basalt stone next each tree.

I think there is still an argument for art to remain “useless” in order for the ideas to maintain their freedom.