Material girl that I am, I love books. Holding them, smelling them, turning their pages, penciling notes in their margins. Finishing one and closing it with a satisfying thap. The Internet is astonishing: I use it daily. But I can’t have a physical relationship with it.

Material girl that I am, I love books. Holding them, smelling them, turning their pages, penciling notes in their margins. Finishing one and closing it with a satisfying thap. The Internet is astonishing: I use it daily. But I can’t have a physical relationship with it.

Navigating cyberspace can’t compare to meandering in and out of printed pages. Accumulating links isn’t nearly as satisfying as accumulating shelves of books and arranging them according to their own, intricate interrelationships.

So I recently added some new volumes to my shelves on surrealism—one of which inspired acquisition of another, which more or less compelled me to obtain the third.

The first, Subversive Spaces: Surrealism and Contemporary Art (2009), documents an exhibition I was lucky to see at the Whitworth Art Gallery, University of Manchester. Its pages are packed with strong writing and evocative images but, as is the case with some exhibition catalogs, this is a souvenir, not a stand-alone object.

In other words, the book mostly just makes me want to see the exhibition again. A printed still from Lucy Gunning’s Climbing around my room video, for instance, is merely frustrating.

Samantha Lackey, who organized the exhibition, writes that although radical, historical surrealism “may indeed have died, its legacy lives on in a contemporary engagement with its interests” as “experience of the spaces around us is altered daily through the advent of new technologies and new economics of globalisation … .” Essays by co-curators David Lomas and Anna Dezeuze are bleak reads, but underscore the idea that surrealism exceeds the activities of a handful of Parisians, during the middle of the twentieth century.

Pushing the boundaries of surrealism seems to be an aim of more than a few British scholars—which helps loosen the grip that Rosalind Krauss and her colleagues maintain on the subject. [For example, http://www.surrealismcentre.ac.uk/ is a joint project of the universities of Manchester and Essex, along with Tate.] The idea of surrealism is further developed in The Surreal House (2010) published by the Barbican Gallery.

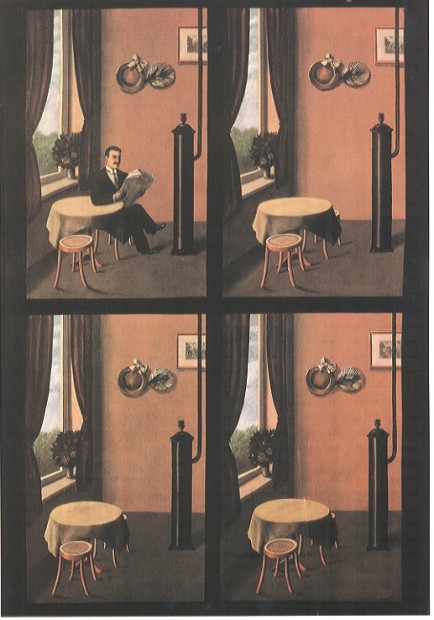

Having missed the exhibition, I use the book as a stand-in. In that role, it’s more than adequate in spite of being excessively clever (providing an index, for example, apparently was deemed naff). The best part is the mix of artists cited, ranging from obvious inclusions like Rene Magritte, Lee Miller and Max Ernst to those less so, such as Louise Bourgeois, Francesca Woodman, John Hejduk and Paul Thek.

The Surreal House also incorporates numerous references to other books, one of which sent me to the library, another, to the bookstore. In the first instance, I visited a nearby college and spent five hours in its library, combing through Walter Benjamin’s The Arcades Project (a 2007 translation). In the second, I bought my own paperback copy of Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space (a 1964 translation).

A few hours couldn’t do justice to Benjamin’s unfinished magnum opus. But even a bit of exposure to the poetic fragments contained therein restores some of the aura that Benjamin and his ideas have lost through endless analysis of his ideas about loss of aura.

As for Bachelard’s book, my new copy already is filled with penciled margin notes, underlinings, and stars and exclamation points. I read Poetics of Space about seven years ago but, after The Surreal House, it seemed new to me. That’s the great thing about re-reading any sort of text, visual or verbal, after exposure to fresh ideas about it.

By all indications, Bachelard viewed life with equanimity, and thoroughly appreciated a cozy home. A phenomenologist, he also was skeptical of psychoanalysis. This initially puzzled me. Why were the surrealists—suspicious about comfort and addicted to psychoanalytic theory—so keen on Bachelard? Ultimately, I chalked it up to selective reading: every text effectively is rewritten by each reader.

My own reader-response to Bachelard? Tuck myself into an overstuffed chair with his book and a freshly sharpened pencil—and do more reading.

____________________________

Janet Tyson is a writer and independent art historian, living in Michigan. She has worked as an artist, art critic, curator, lecturer and art librarian. She was Texas correspondent for The Art Newspaper and regularly contributes to Cassone: The International Online Magazine of Art and Art Books.

2 comments

interesting take on the whole “reading” part of books- and an excellent piece of writing. makes me want to look at more books and more art. thank you.

Thanks for your feedback! It does my heart good whenever someone wants to spend more time with art and books.