You still have time to see the Texas Biennial 2011! It’s up until May 21, extended by a week. At least the main exhibition — curated by Virgina Rutledge, copyright attorney/art historian/former special counsel to Creative Commons — is still up in this large office building at 816 Congress. I think this is sort of the flagship exhibition. There’s also a New Art in Austin: 15 to Watch show at the Austin Museum of Art, and the final curatorial effort of Arthouse’s ex-curator Elizabeth Dunbar as well as Biennial events. But this one is called “TX 11: Texas Biennial” which seems official.

It’s not 100% clear to me which art exhibitions in the state of Texas and on view April-May aren’t part of Texas Biennial 2011, or what, precisely, the parameters are, time-wise. This San Antonio show I wrote about is part of it. But MIXMASTERS: This is who we are, an ongoing series of gallery shows between Austin and San Antonio artists, isn’t.

And the TX Biennial calendar confuses me. At the time I started writing this, the only event to come was a May 5 opening, followed by a list of participating institutions statewide, in alphabetical order, with info about openings and events in each place. So, say, if you were wondering exactly what-all was going on on May 7 in Corpus Christi, you have to scroll down and wade through stuff not organized by date (including Revelations: Women’s Art from the Permanent Collection that opened at the Art Museum of South Texas in February, and continues until January — almost a year?) and which may or may not have any new art in it.

The Biennial’s goal of state-wide inclusiveness, as stated on its website, is a good one — and Lord knows that’s a lot of territory to cover. But, so is the Biennial an imprimatur? A calendar? A cluster of events? A brand? A brand and calendar that is also the name of the exhibition I’m about to talk about? These kinds of civic arts happenings are almost always a little soft around the edges, conceptually. Maybe that’s not a bad thing, but it makes them hard to navigate.

By way of comparison: March is Contemporary Art Month (CAM) here in San Antonio. The fledgling board has its faults and CAM doesn’t encompass the complexities of the Biennial, and the work isn’t as curated, largely (anybody can list an event on the CAM calendar). But its online presence is well organized; the calendar posts events, and their venues, and the artists involved, and hot-links to more info on each variable, all by day like a regular calendar. So it’s easy to look over the whole month beforehand and focus on what you want to see, and to use as reference afterward, to get an overview. Look here, see.

But that’s all logistics. The Biennial now has two years to figure all that out. And meanwhile, Virginia Rutledge has gathered and staged important contemporary art in this two-office exhibition.

Here’s the lobby of 816 Congress, host to what I’ll call the Rutledge Biennial show (despite Rutledge curating several other Biennial shows, including Jade Walker at Blue Star):

I’ve visited lots of art in corporate spaces, but this was a freaky li’l experience, somewhere between gallery visit and Being John Malkovich. I went on a Saturday, and was let into the locked building, eventually, by security guards who talked at me through an unseen speaker.

“The door to your right, ma’am. TO YOUR RIGHT. No, not the revolving ones.”

Once in, I was directed to two floors, the 5th and the 14th, I think. There were signs. The building’s elevator was really plush, and played actual elevator music. Upon arrival at one, then the other floor, I had to sort of look around to find the unfinished offices/exhibition spaces, each of which contained multiple works of art, as well as a young woman acting as host/guard. And in each elevator ride, each floor search and each show room, I was the only viewer, which felt both focus-enhancing and a little surreal.

The set-up is odd, but the search is worth it.

As you can see, the space is far from overstuffed. There’s space for art and viewer to breathe — and for to you approach each piece largely without distraction from the others. This careful footprint allows for a wide range of media, scale, palette, site-specific installation and smaller wall work. The Rutledge Biennial show takes on an impressive magnitude via relatively few works; the ones she chose are doozies.

In the first gallery I visited, I was drawn into an ambitious, immersive, slightly menacing room transformed into a cramped, dystopic interior architecture. It was Kathryn Kelley‘s without your forgiveness I am still bound to what happened between us. only you can set me free.

I didn’t know the title until just now, I looked it up. I’m surprised by the call for forgiveness, but the “stuck” aspect comes at you as both straightforward and arresting; we’re looking at rubber, wood — an aftermath of something ripped asunder. My mind went immediately to post-terrorist sites and other monstrous un-buildings. But Kelley’s assertion of personal narrative, of Kelley/the narrator mired in these drooping outsize hoses and wooden remnants, makes for an explosively potent disaster area of the heart. I find I don’t need to know “what happened between us,” but can reflect on all the battlefields we all live in, still hoping for release, still depending on the actions of an Other who may or may not be amenable, or alive, or comprehending.

I saw some small lights interwoven into the construction, but unfortunately, they weren’t on. Lit up at night, the piece must be particularly wrenching.

Another attention-grabber: Remote and Bilocate, soft fabric architectural sculptures by the El Paso-born, Austin-based Michael Anthony García. Bilocate extends a pair of pants, and the idea of pants, between floor and wall. The meta-pants pants are constructed of several pairs of pants, the legs are stretched to absurd lengths and are in positions that make hay of the physical strictures of the body; two “knees” appear on the left leg, attached to a nifty light fixture on the floor, and the right leg makes an unlikely upwards curvature high on the wall. If there’s a story here, maybe it’s the uninhabited uniform of a contortionist on stilts. Or maybe the pants are inhabited, and the waist-up part of this wild unseen man is on the other side of the wall from the waistband. When I saw deer heads mounted on walls as a small child, I assumed the rest of the buck was outside the restaurant, and had thrust his head through.

But the truth is, the viewer can read a lot into Bilocate, starting with the title — the human being coming from or heading towards two radically different loci simultaneously, a material illustration of ambivalence, the plight of an endangered or outdated masculinity (all the pants are Dad-style corporate business trou), trousers as unexamined bodily fixtures made into whimsical household fixture… The artist leaves you space to think, and declines to judge; the creature-like sculptures don’t judge, either. García’s made his decisions, and in the words of Dave Hickey, “never confess, never explain, never apologize, and never complain.”

The playful ambiguity of his work made me glad I had no immediate access to text of any kind, not wall exegesis or an artist’s statement, or even titles.

García’s Remote is a rumpled creature mostly made of empty shirtsleeves, the “face” is enlightened by light fixture (representing an idea, maybe?) with shoulder pads clustered around it like petals. It makes beauty on its own gracefully hangdog terms. García’s work evinces a female sort of portrait (counterpart?) that plays off the masculinity of the pants. A whole, self-contained being whose light lifts instead of anchoring, as in the case of the case of García’s pants sculpture. This sculpture seems pretty immediate to me, not “remote.” Unless the object, in some narrative, plans to float up and away.

Music emanating from some seemingly distant place gave an aural undertow to the entire office. Muffled and thumpy, it sounded like the interior of an ice house beer joint, like the C&E on Zarzamora Street in SATX, on a jumpin’ Saturday night, as heard from the parking lot. The sound emanated from just beyond the Kathryn Kelley installation, from another (I presume site-specific?) environment which held court in its own small curtained-off room. Once in there, you’re thrust, via a single channel hi-def video projection called 1:1, into the interior of a Tejano dance hall. You could be anywhere from Edinburg to Eagle Pass to Sugarland. It’s familiar stuff; low ambient lighting, cumbia music, swirly colored lights, and bar-wall accoutrements which include neon beer signs and a TV whose advertising broadcasts Anglo faces, but with ad copy legends in Spanish.

In the middle of the dance floor in the video, Austin-born and Austin-based artist Jessica Mallios placed what appears to be a very large, late-19th century wooden daguerrotype camera resting on a wooden stand and pointed at the wall. Mallios’ video captures a group of maybe 20-30 people as they cumbia along in front of her camera around the old camera, some in couples, some by themselves, all apparently Mexican or Mexican-American. The shuffle and gentle spins of the dancers in circular procession hints at ritual, and dance as a unit of social measurement, and even in this most particular of arenas, the universality of simultaneous movement. Some of the members of the processions seem genuinely to be enjoying themselves, and some even seem to grin or wriggle for the camera, while others don’t notice it, or gaze downward and away, their faces serious or careworn.

Dance halls like these, in Latin America, Texas and across the US, serve as places of respite and relaxation for hardworking, often homesick people. But Mallios achieves more than mere documentation of a dance floor; the artificially-circular formation and static camera angle, the precisely-timed 4:13 loop, and the slightly warped-sounding audio track (resulting, maybe, from the acoustics in that room) heightens your consciousness, makes you aware of your own gaze, and makes of a Saturday night at the C&E Ice House a ceremony older than cameras. The dance outlived the daguerrotype and will still happen when digital video’s been replaced. 1:1 is a knockout, and Jessica Mallios is an artist whose work I’ll seek out.

Not everything in this gallery presented so strikingly unusual a face, though there were other fine things, like a couple of Ricardo Paniagua‘s blazing canvases, Fresh Gong Go Bong Bong and Technological Marvel, which each posit mathematically elegant, shadow-casting artificial structures against a pink-splattered “wall.”

The closely set rectangular “columns” almost suggest some particularly difficult-to-read font. Set in the back room down the hall, they’re smart, nifty pieces.

In the larger gallery, on the opposite side from the enclosed rooms, Catherine Colangelo’s Fleet for Abby Boat series of gouaches present a beautiful suite of fanciful vessels, each loaded with lovingly exact details, yet slightly abstracted. Each boat is named after a woman.

The boats take the shapes of galleons and junks. The feminine reconquista, here, of making these ships so graphic and so imaginative rather than an ironic paint-by-numbers “take” on nautical art, strikes me as radical.

A problem: due to the overhead fluorescent lighting, it’s hard to get images – or proper in-person views – of works behind glass, which was frustrating. I ran into this problem with several 2-D wall pieces. I was attracted to Clarke Curtis‘ Haute Helping Hands intimate-scale collage series. They are delicately constructed, somehow Waiting for Godot-like pairs of beautiful monsters in mutual need, made from tiny cut-outs of consumer luxuries — like Bosch’s bizarre hybrid creatures but more fun, and more modish. They reach out to each other in tenderness and solidarity. But the light was dim where they’d been hung and you can’t tell all that from this image:

RISD-grad Katy Horan‘s exquisitely detailed, mysterious neo-shamanic gouache busts suggest monsters of lace and filigree, commanding as kabuki, but signposts in a personal mythos.

But note glare, reflections of other work, and accidental image of the photographer. It was more rewarding to pore over these delicacies of the uncanny in the (fantastic) TX Biennial 11 catalogue.

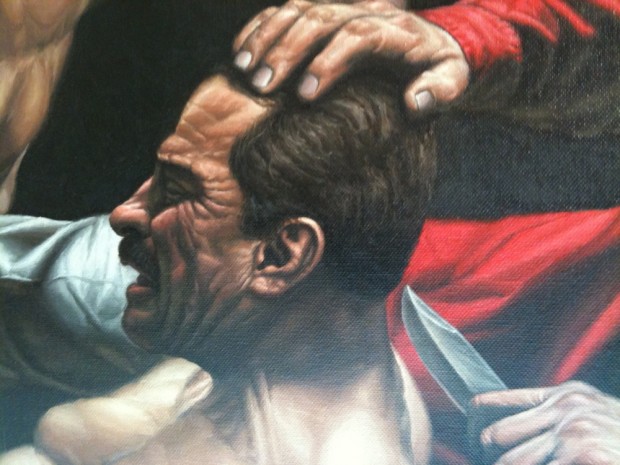

In the second exhibition office I entered, I came face-to-face with a heroically-sized canvas by Rigoberto A. Gonzalez, a phenomenally technical, exacting and passionate Old Masters painter (under the age of 40) from Reynosa, Tamaulipas, Mexico, now residing in San Juan in the Rio Grande Valley.

Even under fluorescents and whatever you call that kind of ceiling, powerful stuff, especially in person. Unfortunately the canvas shows some pucker.

I’ve been watching this artist from afar, always wanting to write about him. For some years now, Gonzalez has dedicated his figural painting to the ongoing brutality and complex moral landscape of the border, in which we’re all implicated. He depicts each act of violence and desperation with the gravitas of a major historical event, all the while knowing this is a daily order of business. The preoccupation with beheading is maniacal in Mexico’s drug wars, but has Biblical and Baroque underpinnings as well — think Judith and the Head of Holofernes.

An alum of the New York Academy of Art who once traveled to the Netherlands to make sketch studies of Rembrandt, Gonzalez harnesses his considerable power in The Zetas Cartel Beheading Their Rivals (Se Los Cargo La Chingada) via paint handling, expressive human expression, solid triangular composition, judicious saturated color and chiaroscuro — to make clear a viable, modern tragedy with Baroque gestures and techniques. He both depicts a murder scene semi-editorially, remarking on the 25,000 dead and millions in terror not so very far from this building on Congress, while making reference to what Velasquez and Goya and Orozco have reminded previous generations; life is fleeting, and cruelty, among other things, makes for a good picture).

That Gonzalez paints so masterfully and seemingly without irony, and that his near-devotional works (he’s also rendered commissions for several Catholic churches in South and Border Texas; this is moral cosmology he’s taking on, as well as historical technique) makes the Rutledge Biennial Show all the more innovative. That Gonzales’ 2-D grito, with its saints and corpses and unvarnished injustice, should show alongside Nicholas Hay’s gesso-on-wood statement, I Ain’t Got Nothin’ To Say, an outcry that could be read as honest cop-out or vacuous gesture or both (and I like that), speaks to a complex curatorial mind at work, who can reconcile work of social justice with work of social ambiguity.

Also on this floor, I admired a blocky-handsome and solidly harmonious painting of Houston-based Marcelyn McNeil and a duo of unusually-shaped paintings by San Antonian Richard Martinez. They are abstracts, beautiful, well-executed and intellectually provocative enough to transcend the decorative (even though Martinez’ Bellatrix hints at the decorative with its sly stylized flower). I would gladly live with these. I wish I had the money to make it happen. Solid, un-wispy beauties, calling up domiciles, livestock, clouds, dreams. Excellent companion pieces.

“Those Martinez paintings must have been hellish canvases to stretch,” I thought.

Scrutinizing closely, it’s clear they were; as lovely as they are, these works arise from pure rigor.

Here’s a gallery view of this 2nd space.

Not-so-great gallery view, but gives you an idea of the curatorial restraint, and space alotted

Rutedge’s Biennial show presents aesthetic fantasies and regional commentary, whimsy and tragedy and fruitful confusion. There were works that didn’t, at least in that context, win me over; Brent Ozaleta‘s work presented brilliantly-designed wallpaper, the impression heightened by, well, papering a column. It’s attractive, but in this context, more graphic than compelling.

Cassandra Emswiler‘s Hemispheres / Spacia bridge / Austin-Houston 2011 takes linoleum flooring and spreads it with what seem to be found objects from nature; a wad of ball moss, sculptural sea-weathered wood, pebbles and other tokens (mostly) from the natural world. But it feels formulaic and the poetry it almost makes doesn’t come through clearly. If all it is is nature vs. un-nature, OK. But there’s perhaps something I’m not getting, like there’s an earnest lesson gone uncommunicated.

I felt similarly about Shannon Canning’s Razer, which is a perfectly good painting of a ray gun. It looks like a film prop, a vintage toy, an object of desire. It’s a very, very good painting of a ray gun, about which I wondered how to write. And I still haven’t figured it out.

TX Biennial at 816 Congress: Office Space

816 Congress is open Mon-Sat, 12-5 pm

Through May 21

1 comment

always wondered if Rick Martinez makes his own frames