So I acknowledge it’s from a fanboy’s perspective that I write about the current exhibition at the Nasher Sculpture Center, The Art of Architecture: Foster + Partners. Here are the familiar accoutrements of an architecture practice – intricate scale models, sketches on tracing paper and big photographs made with heavy Hasselblads. I almost miss the smell of ammonia from the diazo blueprint machines.

Foster + Partners...Sketch for Swiss Re Headquarters...30 St. Mary Axe, London (1997–2004)...© Foster + Partners

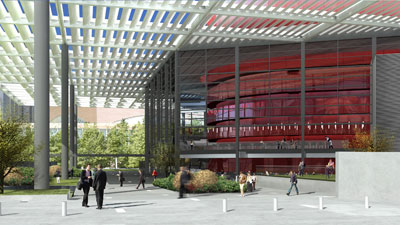

The scope of projects represented by the 43 architectural models is extensive: not only cultural facilities like Dallas’ new Margot and Bill Winspear Opera House; but also infrastructure like the Millau Viaduct, bridge-cum-modernist sculpture that spans the 1.5-mile Gorges du Tarn in southern France; and one of the most revolutionary office buildings in the world, the dirigible-like headquarters of Swiss Re at 30 St. Mary Axe in London, dubbed "the gherkin."

But to make this just about the models is to celebrate the craft, not the art. Then you might as well take in the State Fair’s 4H displays and science fair projects with a corny dog. Instead, these models are aliases, stand-ins, not only for buildings but also ideas too big to get through the door. More like fine art than the pure science of engineering, the applied art of architecture can be nuanced, pregnant with meaning and yet open to interpretation.

The part of the exhibition that literally illustrates this aspect best is modestly displayed behind the stairs on the Nasher’s lower level. There, among the aforementioned sketches on tracing paper, is a small group by Sir Norman Foster himself, excerpts from the laborious studies for a giant steel eagle now hanging in the chamber of Berlin’s Reichstag building, seat of the New German Parliament (one of the flagship projects represented by models in the main gallery).

In the midst of the design process in the ’90s, Foster, also an accomplished product and graphic designer, spoke of working with this lightning rod of a logo, one that just 50 years earlier had ranked second only to the swastika as Hitler’s national emblem. "You can imagine that, given Germany’s history this century, I have to get the turn of the head, the length of the talons, the position of the wings exactly right." He added, "What is truly astonishing is that the Bundestag should commission an Englishman to design such a politically sensitive symbol."

"Light, airy, structurally daring, with breathtaking views across Berlin as the sun plays on the mullions and ripples across the floor. The elegance and simplicity of the dome cause the visitor to catch his breath," the London Telegraph reported in 1999 when the seven-year project was finally completed, describing the reflective funnel as "a lighthouse mirror in reverse, pulling natural light down into the chamber far below…"

Unfortunately their assessment concluded, "…which makes the dullness of the rest of the building all the harder to accept."

Yes, while Foster + Partners’ original proposal, the one that won the competition for them, had promised not to disappoint, change is the name of the game in such massive, commissioned architectural projects; push and pull part of the design process. Budget cuts scaled back the plan drastically, deleting an extended roof and pedestal that might have eased the lumpish structure’s gravitas. The cuts also limited reconstruction to what would be done within the walls of the original building itself. Other than some cosmetic touch-ups on the interior, the glass cupola and mirrored funnel would be the only significant features to survive from the original design.

And here’s where the models in the Nasher exhibition come into their own, as they demonstrate not only the imaginative solutions propagated by the firm’s internal design charrette, but also the real-world compromises necessitated by client demands. Leading a walking tour prior to the exhibition’s opening, Foster + Partners’ head of design, Spencer de Grey, acknowledged the setbacks without complaint, and further, redeemed them by describing how orphaned ideas sometimes find a home in subsequent projects.

Foster + Partners...Computer Visualization of the Margot and Bill Winspear Opera House...Dallas Center for the Performing Arts (2003–09)...© Foster + Partners

Here in Dallas, amidst the current hyperventilation surrounding recent arts district architecture, where the chant, "Pritzker-Prize winner…Pritzker-Prize winner" can be heard wafting about, "The Art of Architecture" might seem a little too timely, as if staged by the chamber of commerce. Or if you can’t get past the models, it could look like just so much balsa wood. But you have to be willing to see beyond what first confronts you to find the intent, like the first time you saw a Guston. There’s an art to it.

The Art of Architecture: Foster + Partners

September 26, 2009 – January 10, 2010

Nasher Sculpture Center

Dallas

James Michael Starr is an assemblage and collage artist who lives in Dallas. He is represented there by Conduit Gallery and in Houston by Hooks-Epstein Galleries.

Also by James Michael Starr:

{ Review }

Diego Rivera: The Cubist Portraits, 1913-1917 at the Meadows Museum

1 comment

Great Review … I loved this show and think everyone should see it. But be warned, no photography allowed. They will tackle you (literally). Compounding this frustration, they do not even provide photos to the press of the exhibition (of the models)!? They are super impressive. Perhaps these will come out later, but I can’t believe how this issue of photography is still a grievance.