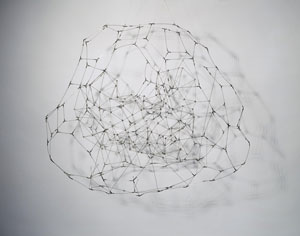

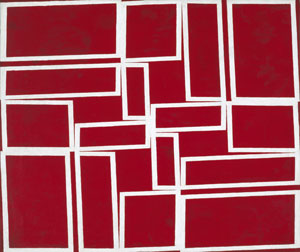

Hélio Oiticica, Vermelho cortando o branco...(Red going through white), 1958...(Image details below)

Museum curators lead interesting lives in our interesting times. Exhibitions are planned years in advance and, so, are vulnerable to the sudden shocks of wars or terrorist attacks, the chilling (or heating) of relations between nations and/or political blocs and the exigencies of a globalized economy. So when the Tate Modern elected to cancel the North American tour of its survey of the work of the Brazilian conceptualist Cildo Meireles after two of the three venues for this hemisphere pulled out (one suspects due to recessionary pressures, though one doesn’t know), the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, found itself with a rather large hole in their year to fill. The much-anticipated Meireles survey was scheduled (even as late as January of this year) to open in June and run through September; in its stead, the MFAH has mounted North Looks South: Building the Latin American Art Collection, a sumptuous appraisal of the MFAH’s efforts in this area. One still misses the Meireles, but the disappointment is now considerably mitigated.

The MFAH has been very busy. With Mari Carmen Ramírez as Wortham Curator of Latin American Art since 2001, the MFAH has been on an aggressive acquisition campaign as it positions itself to be the center for the study of this heretofore largely ignored area. Of the 102 works in this sprawling exhibition, the majority have been acquired in the last six or seven years; thirty-seven of these works are loans. In addition to highlighting this burgeoning collection, North Looks South provides, if not an encyclopedic overview, then a reasonably thorough survey of modern and contemporary Latin American art.

Curated by Ramírez and Gilbert Vicario, formerly assistant curator for Latin American Art (now curator at the Des Moines Art Center; he will be missed, and it would behoove us all to keep the Center on our radar), the exhibit is rather neatly bisected; enter the from the east stairway and you are met by a very different show – cool, apolitical, for the most part formal in its concerns, even utopian – than the one that greets you from the west stairway, where the work is more expressionistic, politically engaged and decidedly dystopian.

The works in the two central galleries are at the heart of North Looks South, physically and conceptually. The first is largely dominated by selections from the Adolpho Leirner Collection of Brazilian Constructive Art, works from the late 1950s and the 1960s and acquired by the museum in 2007, while the second features an older generation of Latin American artists. The Leirner Collection focuses on a brief but important moment in Brazilian art when several groups, primarily in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, drew from Russian Constructivism and Dutch Neo-Plasticism the general elements of a concrete art, abstract and idealist. Among them was the innovative and influential Lygia Clark; her work would later evolve from a constructivist idealism to a more conceptual practice. That transition can be seen here in the two assertive 1957 paintings, Planes on Modulated Surface No. 1 and No.5, and two nearby, more suggestive, sculptures from 1962, Bicho (Máquina) or Critter (Machine), and, from 1965, Trepante or Creeper.

But these artists are not sui generis; across from the crisp black-and-white intersecting planes of Waldemar Cordeiro‘s 1956 painting Idéia visivel (Visible Idea) hangs Joaquín Torres-Garcia‘s Composicíon abstracta tubular (Abstract Tubular Composition) of 1937. Torres-Garcia is largely credited with grafting European modernism on to South American artistic traditions upon his return from Europe to his native Uruguay in1934. His El Taller [Workshop] Torres-Garcia in Montevideo trained such artists as his countryman Julio Alpuy, whose Genesis (1964), a large pictorial sculpture (or sculptural picture) made of wood, paint and ink, hangs in the next gallery.

But those abstract tubes also inform the work of other artists, such as the Venezuelan Gego (born in Germany in 1912 as Gertrud Goldschmidt), her fellow Venezuelan Carlos Cruz-Diaz and an Argentinean, Gyula Kosice, on the more utopian side of North Looks South. Gego’s Esferas (Spheres) and Reticulárea may look like sculptures, but they are drawings executed in space (even her recognizable drawings are suspended in front of the wall). Cruz-Diaz’s pattern-shifting explorations of pure color marry formalist language with the exuberance of color. Though the majority of them hang on walls and they are decidedly pictorial, there is also something of the sculptural about them; they extend into space physically and optically, seeming to project color into the immediate space. This becomes literal in Chromosaturación (Chromosaturation), a chamber divided into three semi-rooms, each bathed in red, blue, or green light. After donning some stylish blue booties, you are invited to enter the chamber and experience the physicality of light (it’s easily the most popular work in the show, and, dated 1965, it predates by about four decades some similar recent installations by James Turrell).

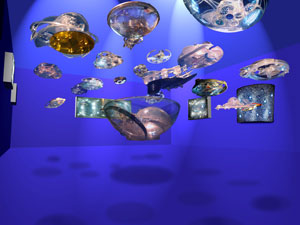

Now in his mid-eighties, Kosice founded a movement called Madi (when I figure it out, I’ll get back to you) and is represented by several wall sculptures from his ongoing career, at least two of which involve light and water. But his most astounding contribution to North Looks South, and the Museum’s most recent acquisition for the Latin American collection, is an installation he worked on from 1946 to 1972: La Ciudad Hidroespacial (Hydrospatial Cities). It’s a kind of Roadside South America-meets-the-Jetsons: a room filled with models of flying platforms (an animated video on the way in indicates they are conceived as non-stationary), domed with Plexiglas or acrylic and detailed down to the little people inhabiting these pods.

The second gallery at the center of North Looks South, the "old masters" gallery, contains works by the Surrealists Roberto Matta, from Chile and Wilfredo Lam, a Cuban, alongside works by Mexicans Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros and Frida Kahlo, among others. The sociopolitical concerns of Rivera and Siqueiros, the autobiographical obsessions of Kahlo and the surreality of Matta and Lam inform the more contemporary artists and their works which tilt the exhibit toward the dystopic.

In the midst of the "old masters" stands La sordidez (Sordidness), a 1964 sculpture by Argentinean Antonio Berni, from a series entitled Monstruos cósmicos (Cosmic Monsters). Just over thirteen feet long, it is vaguely the image of a chameleon, comprised of a panoply of materials (the checklist lists them, but it wouldn’t help) that add up to a completely over-the-top monstrousness that almost goes around the corner to end up as farce. On my first encounter with Sordidness, several years ago in a different exhibit, my initial impulse was "What the f***?" and then to laugh out loud – but it was laughter tinged with a decidedly unsettled undertone.

That undertone continues with Argentinean Miguel Angel Rios‘ two-channel video installation White Suit (2008). A man, wearing the titular suit, stomps out a Latin dance, rhythmically twirling sizable pieces of meat from the ends of ropes. Pretty soon, someone releases the hounds heard off-camera and they go for the meat – and the dancer’s arms and hands, as well. The whole thing speaks to machismo and blood and rituals of sport and death.

Outside the installation, this theme continues in the work of Oscar Muñoz, a Columbian, and Teresa Margolles, a Mexican. Margolles’ Lote Bravo (2005) is comprised of 400 mud bricks forming two low, close and parallel walls. The dirt to make the bricks comes from the killing fields around Ciudad Juarez where the bodies of thousands of murdered women have been found over the past several decades.

Margolles’ wall connects two of Muñoz’s works, hanging on opposite walls: Narcissos Secos, series de nueve (Dry Narcissi, Series of Nine) from 1999 and Pixels (2003). Both are a series of portraits based on photographs of men killed in the political and drug-related violence in Colombia over the last thirty years; the media in Narcissos is unfixed charcoal on Plexiglas, while in Pixels it is sugar cubes stained with coffee (two staples of Colombia’s economy), mimicking the digital units of the title.

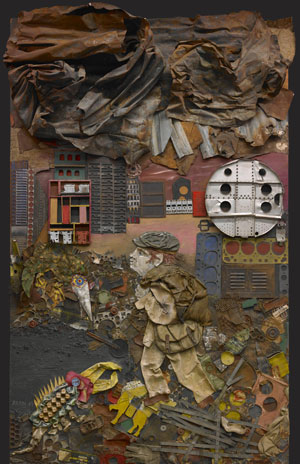

Just beyond Margolle’s walls and around a corner, a room holds Chilean Alfredo Jaar‘s The Eyes of Gutete Emerita, an installation that universalizes Margolles’ and Munoz’s concerns (I reviewed it for Glasstire in 2005 when it was first shown – it’s good to see it again). Another work by Muñoz, Ambulatorio, from 1994-1995, lies on the floor nearby. Borrowing from Carl Andre, Ambulatorio is a number of tiles made of large aerial photographs of a city framed in safety glass, which has been shattered. The city is Cali, home to the notorious Colombian cocaine cartels of the 1980s and early 1990s who made the city one of the most dangerous in Colombia. The aerial photos are not laid out contiguously to form a sensible view of the city, but randomly, undermining any attempt to find continuity. Nearby, Antonio Berni’s Juanito va a la Ciudad (Juanito Goes to the City) from 1963 depicts, in all kinds of found detritus assembled on board, a young boy trying to find his way – and a future – in just such a city.

The installation of North Looks South recalls curator Ramírez’s groundbreaking exhibition of 2004, Inverted Utopias, in that the works are not presented in a March of History chronology, a this-movement-begets-that-movement-begets-that-other-movement template, but, rather, in what she termed at the time "constellations," loose, non-chronological groupings of works of art that seem to have something to share with one another and with the viewer. It makes for an invigorating aesthetic encounter, as museums around the country are beginning to realize (see MoMA’s reinstallation of its collection). And, speaking of MoMA, the MFAH is positioning itself to do for Latin American art what William Rubin did for (or, some might say, to) European Modernism at that venerable institution: write the history and define the canon. So far, the history seems more elastic and the canon more inclusive than many previous attempts at totalizing and defining human creativity. North Looks South shows the progress made thus far, and shines with the promise of what lies ahead.

North Looks South: Building the Latin American Art Collection

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

June 7 – September 27, 2009

John Devine is a writer living in Houston.

Also by John Devine:

{ Review }

"Making It New: The Art and Style of Sara and Gerald Murphy" at the DMA

{ Review }

J.M.W. Turner at the Dallas Museum of Art

{ Review }

"Where Clouds Disperse: The Ink Paintings of Suh Se-ok" and the Arts of Korea Gallery

{ Review }

"Mary Heilmann: To Be Someone" at the CAMH

Image details:

Hélio Oiticica, Brazilian, 1937-1980

Vermelho cortando o branco (Red going through white)

1958

Oil on canvas

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; The Adolpho Leirner Collection of Brazilian Constructive Art, museum purchase with funds provided by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund

(c) Projeto Hélio Oiticica

Gego (Gertud Goldschmidt), Venezuelan, born Germany, 1912-1994

Esfera Nº8 (Sphere Nº 8)

1977

Steel wire and iron leader sleeves

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; gift of the Fundación Gego

(c) Fundación Gego

Gyula Kosice, Argentinean, born 1924

La Ciudad Hidroespacial

1946-1972

Acrylic, Plexiglas, paint, and light

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; museum purchase with funds provided by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund

(c) Gyula Kosice

Antonio Berni, Argentinean, 1905-1981

Juanito va a la Ciudad

1963

Wood, paint, industrial trash, cardboard, scrap metal, and fabric assemblage on board

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; museum purchase with funds provided by the Caroline Weiss Law Accessions Endowment Fund (c) Jose Antonio Berni