Cynthia Norton...Dancing Squared, 2004...Aluminum, hardware, electric motors, dresses, wire...90x180x180 inches

A few years back a heavy package arrived at my door, addressed to my then-husband. Inside was a bronze statue of a realistically rendered cowboy riding a bucking bronco. Perfectly hideous. Think George H. W. Bush statue at Houston Intercontinental Airport. Who would send us such a thing?

I used it as a centerpiece for dinner parties. It got a lot of laughs. After the joke wore thin, I used it as a doorstop.

We later discovered that the statue had been intended for a wealthy and powerful member of the UT Longhorns alumni association who had the same name as my ex-husband. The man sent a special courier to pick it up and was none too pleased when I refused to re-package it.

Months later, my husband came home with an issue of Time magazine, opened to a picture of George W. in the Oval Office. In it, Bush grinned and shook hands with folks in his good ol’ boy fashion. Behind him, on a shelf, was either the statue — our statue — or a replica by the same artist.

No doubt Bush viewed the statue as a symbol of American ruggedness and independence — something he desperately wants to be identified with. I viewed that little slice of Americana as pure kitsch.

The Old, Weird America, currently on view in the main gallery at the Contemporary Art Museum Houston and organized by CAMH senior curator Toby Kamps, tells a more nuanced story. There are many cowboys, Indians, dead presidents and American battles, but I’m pretty certain none of them will wind up in the Oval Office or as Franklin Mint figurines. There’s neither flag waving nor burning; the better pieces in this overall strong and moving show transcend these stereotypes by making things personal. In selecting works that avoid the usual responses to such material — nostalgia, irony, cynicism — Kamps allows us to appreciate the complexity of the iconic.

The title of the show, taken from Greil Marcus’ book on Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes and his exploration and adaptation of traditional American folk music of the late 1920s and early 1930s, gives us a clue to the kind of appropriation going on in the works gathered here. In channeling the spirit of a bygone era by acting out his own personal fantasies of Woody Guthrie, Dylan managed to reinvent an American icon (who had by then become a sweetened-up cliché) so that it spoke to an entire generation. We might also recall that Kerouac, too, created his beat persona from a fantasy America of hobos and the kindly prairie homesteaders who would give them a bite to eat and some temporary shelter. The ambiguity of these literary and musical antecedents to this show is well expressed by a character in a recent Jeffrey Eugenides story who, upon contrasting the Americas of Alexis de Tocqueville to that of Karl Rove: "One’s country is like one’s self. The more you learned about it, the more you were ashamed of." But in regard to one’s country, as to oneself, both shame and pride are finally too simple. The truth, as the artists represented in this show suggest, is to be found only in re-imagining the icon with the work of the hand, shaping its odd and often hallucinatory details.

Nothing could be odder, for example, than Allison Smith‘s seven life-sized figures dressed in period Civil War garb. Smith uses Civil War imagery in most of her work, and it’s a given that her viewers are meant to come away with a sense of the atrocity and pointlessness of war, but this sense is impossible to separate from a more personal meaning. She handcrafts the heads in France, using old-fashioned techniques; they look like her and bear a wistful half-smile. All of the costumes are hand-fashioned from period materials, and some replicate those of a relatively obscure troop of Civil War soldiers called the Zouaves, who fought on both Union and Confederate sides. Their attire makes them look more like cross-dressing acrobats than men of war.

Smith, an openly gay woman, is clearly fascinated by their sexual and political ambiguity. But for us this “message” is inseparable from the weirdness of Allison Smith’s vision: Bodies are strewn about the gallery floor like downed soldiers, but they are set before a beautiful painted tarp, and the absence of blood and gore denies any trace of violence. The reference to battle becomes play: as soon as that gigantic little girl gets back from cookies and tea, she’ll return all those enormous dollies to their shelf.

Sam Durant...Pilgrims and Indians, Planting and Reaping,...Learning and Teaching, (2002)...Mixed Media on Motorized Platform

By working with various goofy aspects of our culture, Sam Durant, Greta Pratt and Cynthia Norton also provide us with odd, funny, multi-layered experiences. Durant’s Pilgrims and Indians, Planting and Reaping, Learning and Teaching — a life-size, split diorama set atop a slowly revolving mechanized platform– is one of the first things on view. On one half, a Native American teaches a Pilgrim how to fertilize the soil; on the other, Captain Myles Standish kills the Pequot Indian Pecksuot. Nothing could be more pat than the overt message of this piece: the clichéd contrast between myth and reality is a standing temptation for any work dealing with icons of Americana. But by presenting it in the form of those creepy dioramas familiar from the natural history museum — with their crusty terracotta-toned skin and bad wigs — Durant taps into the phantasmagoria of childhood, and with it our uncanny sense of loss.

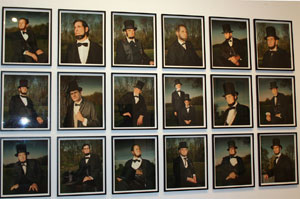

Greta Pratt’s 19 Lincolns, in which the artist photographically documents men across the country who impersonate Abraham Lincoln, also focuses on an unabashedly hokey aspect of how Americans embrace their history. Pratt presents formal portraits (and, in a catalogue, stories) of each "Lincoln" — none of whom particularly look much like Honest Abe — and makes us wonder, who does this? Why? And, more importantly, who goes to see them? That there’s a necessity for these fellows, as there might be for a clown at a child’s party, is pretty bizarre.

Another work, Dancing Squared by Cynthia Norton, demonstrates that there is a strain of American sensibility in which no line can be drawn between the beautiful and the absurd. Four beautifully constructed traditional square dance dresses in bright red, filled out with white petticoats, hang on a rotating metal aperture that looks something like a cross between a clothesline and a dry cleaner’s mechanized rack. It is crowned with half of a mirrored disco ball. At first standing mute and inert, the dresses are set into a sudden, violent twirling motion, as if obeying the call of an “Alaman Left!” Norton’s piece revels in the quirkiness of American culture: while it might seem more flattering to have La Boheme and The Ballet Russe as your cultural heritage, she shows us a strange beauty in Oklahoma! and Saturday Night Fever. It ain’t much, but it’s home. Norton even provides a homemade still called Fountain (emotion) to make that Saturday night complete.

The still and the wildly spinning red frocks evoke another element that emerges in The Old, Weird America: Puritanism and its constraints. Dancing — even square dancing — is a form of intoxication, and as such it belongs in the iconology of Americana as both taboo and ecstatic vision. Dario Robleto‘s Shaker Apothecary (with A Rosary for Rhythm and Salvation Cocktails) makes this explicit. The chest of drawers, constructed with Shaker simplicity and functionality, is labeled with contents like "Do the Hand Jive/Rose of Jericho" and "Walk the Dog/Gravel Root," reminding us that those same Shakers sought signs and wonders. And even back then, Robleto’s piece suggests, you might hafta get a little somethin’ in ya to get some shakin’ goin’ on.

Dario Robleto...Your Lullaby Will Find a Home in my Head, 2005...(See complete materials list below.)

Robleto’s recurring musical theme is prevalent, and, like Allison Smith, the heart is in the details. Your Lullaby will Find a Home in My Head — a small frame with three coarsely braided plaits — is at first simply an homage to Victorian framing and hair artistry. But when one learns that the tiny braids in the picture frame are stretched and curled audio tapes from a recording of Sylvia Plath reading her poem November Graveyard, and that the frame itself is paper made by hand from soldiers’ letters, the artist, with tender regard for the suffering it involves, shows us how our icons embody a history accessed only through feeling.

Empathy and personal culpability in the face of one’s past is a subject visited frequently in The Old, Weird America; Kara Walker‘s nearly 16-minute video 8 Possible Beginnings or: The Creation of America by Kara E. Walker being a good example. This is a wild collection of short plays that harks back to the 1800s with shadow puppets, scratchy, skipping old-timey music and flickering light. Walker presents her familiar version of The Song of the South: sexually perverse, violent and scathingly critical of past and present race relations. The medium’s rustic simplicity contrasts sharply with what it presents. For instance, one hears the voice of Walker’s daughter saying, “I wish I were white,” or sees the seedling a slave plants at the beginning of one narrative grow into the tree he hangs from.

While the “innocent” old medium of shadow puppetry can be a vehicle for uncovering layers of collective and personal horror, the hackneyed icons of Americana can also lend themselves to less disturbing — though equally complex — forms of visual expression. Brad Kahlhamer‘s watercolor and ink works scramble “Indian” stereotypes — totem poles, buffalo, arrows, warriors and what-not — with armies of skulls and sometimes sexy, sometimes forlorn Goth-looking chicks. Kahlhamer creates powerful images of how each of us, in our own way, must stylize all this cultural detritus, for there is simply no escaping it.

A similar insight is won from Barnaby Furnas‘ vibrant dye and urethane paintings on linen — bloody, bright depictions of Civil War battles, representations of Abe Lincoln and John Brown as sacrificial lambs — that have the chaotic look of Ralph Steadman illustrations or stills from South Park. These, too, seem to be caught between two worlds. Though on one level they belong to the “horrors of war” genre, their feel is pure pop-culture. As did Dylan with the musical culture of his time, Furnas filters the iconic through the visual culture of ours.

I was in Florence recently, staying at the country home of a friend who is Italian by birth but was raised in London. He had some young jazz musician on the stereo, and asked me if it was ok; if I liked it.

“Sure,” I said, “why not?” He said that he detested American country music. I said that I loved it.

“I can’t stand that steel guitar,” he said. I didn’t know what to say. I love that steel guitar. Finally, I said,

“Even Hank Williams?”

“I don’t know who that is,” he replied.

It’s not necessary to love Hank Williams or that steel guitar to appreciate The Old, Weird America, but the artists in this show who seem to be in touch with their own brand of metaphorical twang are the most effective. Others — the ones who’ve turned the volume down, muted it, or cleaned up that sticky, embarrassing mess of the American icon — have a bit less visual potency.

Deborah Grant‘s grid of acrylic painted birch panels, Where Good Darkies Go, suffers because the imagery, appropriated from outsider artist Bill Traylor, is bled dry by the clean, minimal format. Unlike the visuals in Kara Walker’s work, these feel too easy and affectless, and so do not touch us very deeply. The simplistic lines and the Judd-like format say salon more than “Y’ain’t from around here, are ya, boy?” Just not old and weird enough, I’m afraid.

The same can be said for Jeremy Blake‘s 2002 video Winchester. I’d seen this at the 2002 Whitney Biennial not long after I’d written about his fluid, painterly, abstract videos shown at the Blaffer Gallery in Houston. The rolling shapes of the abstract works were gorgeous and soothing, and the representational imagery in Winchester is equally so. And that’s the problem. This video was inspired by the Winchester Mystery House in San Jose, California, and its eccentric owner, Winchester rifle heir Sarah Winchester. Although the work has an appropriately dreamy, ghostlike feel (Ms. Winchester was apparently so influenced by psychic predictions, she kept her house under construction to ward away spirits angered by the killings from her family’s guns), it’s the floating, underwater effect that gives it less of an edge. It’s more Fantasia than There Will Be Blood. Curiously, these two examples suggest that the one thing that old, weird Americana cannot tolerate is to be aestheticized.

Also, while Kamps’ inclusion of McDermott and McGough lets us savor a different visual idiom — that of fashion plates and “olde tyme” dandies — the kitchy look and feel of these works is inert until one consults the wall texts. Perhaps I’m a tad thick, but I’m not sure I’d grab the references to Oscar Wilde’s lover and the shame of homosexuality in late nineteenth and early twentieth century America by simply looking at the paintings and sculpture. We learn that the artist duo actually “lived in the past” for a period by lighting their East Village apartment by candlelight, driving an old Model T and dressing like dandies. While that is an interesting gesture to consider, it prompted this viewer to wonder what they did about plumbing, and if that was period as well. Also, considering how commonplace eccentricity can be these days, what is really to be gained by strolling down a street in late 20th century Manhattan in a top hat? I recently spotted Tom Wolfe on Manhattan’s upper West Side looking like something out of The Great Gatsby. He must be making art every day.

French novelist George Sand, born in 1804, scandalized society by sporting men’s clothing and smoking a pipe. It would be difficult to imagine any affectation or eccentricity getting more than a passing shrug of the shoulders these days.

But these are small exceptions, and they don’t detract from the overall mood of the show which is sincere, authentic, complex and quite frankly, a lot of fun. One of its most delightful aspects is the way the curator has apparently himself adopted the pose of another American icon: the carnival barker. Inside the tent, one recognizes (sometimes with a shudder and sometimes with a smile) that the bearded lady and the two-headed chicken are us.

And let’s not forget Main Street. Margaret Kilgallen’s Main Drag is without question the star of The Old, Weird America. Though she probably never consciously decided to step back in time and become a character out of a Charles Bukowski or John Fante novel, she plays that role here with perfect pitch. The genius of Main Drag, which looks like a chunk of cartoonized old L.A. slapped down in the CAMH, is that Kilgallen’s world is both lost and still in existence. It has the grubby feel of that old Mobil station on the corner that never sells anything but is still inexplicably in business. A pile of old soap slivers, spilling from a hole in one of the walls, is delightfully disgusting — truly vintage, in colors that soap doesn’t come in anymore. Unlike the artists who can only channel their chosen periods, Kilgallen’s romance is with a past she actually occupied. Main Drag has a dated feel, but one only has to wander over to L.A.’s Highland Park and step into Mr. T’s Bowl to know that hidden just behind the townhomes and “heritage” restorations, this old, weird America still exists.

This show made me walk away with a rare feeling: that curator Toby Kamps’ passion and investment in this subject equals that of his artists. There’s an aspect that reminds me of filmmaker Todd Haynes ‘ works — not just the recent Dylan "bio-pic" I’m Not There, but of Haynes’ earlier Superstar, which explored the turbulent life of ’70s pop star Karen Carpenter with Barbie dolls and political footage of the time. Haynes, like Kamps, shows us that, hokey or cornball, these subjects are an inextricable part of our identities. The Old, Weird America sparks a certain self-recognition. Painful at times, but also funny, haunting and silly, this show is my kind of weird.

The Old, Weird America

May 10 – July 20, 2008

Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston

Laura Lark is an artist and writer in Houston.

Also by Laura Lark – Lifting – Theft in Art

Dario Robleto Your Lullaby Will Find a Home in my Head, 2005

Hair braids made from a stretched and curled audio tape recording of Sylvia Plath reciting "November Graveyard", homemade paper (pulp made from soldiers’ letters to mothers and daughters from various wars, ink retrieved from letters, sepia), excavated and melted bullet lead, carved ribcage bone and ivory, mourning dress fabric and thread, silk, mourning frame from another’s loss, walnut, glass. 26 x 3.5 x 30 inches.

All photographs by Laura Lark.

– the management