“New Photo?” I overheard somebody say about the FotoFest show of the same name. “A lot of those pieces were, like, 10 years old.”

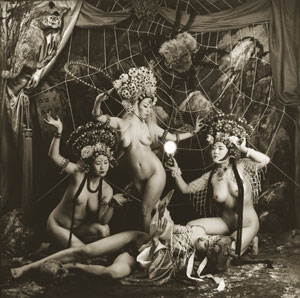

Liu Zheng...Quelling The White Bone Demon, 1997...Courtesy Three Shadows Photography...Centre, Beijing

The uninformed indignation of this charge was not entirely the speaker’s fault. New Photo, 1994-1998 was the backdrop of FotoFest’s opening night celebration, and therefore, most viewers’ first exposure to contemporary Chinese photography. Unfortunately, New Photo doesn’t make a spectacular first impression, and it’s only with an understanding of its turbulent origin that the power of the work can emerge.

Once they read the wall text, viewers learned New Photo was the name of an underground magazine—a zine, essentially—that two Beijing artists photocopied, hand-bound, and self-distributed in the mid-90s (all 30 or so copies of each of the four issues). The 16 artists who showed in New Photo (first the magazine and now the FotoFest exhibition) now constitute “the backbone of contemporary photography in China today,” according to the catalogue essay. Why, then, does the work look so unimpressive? As with everything in FotoFest’s program this year, social history goes a long way in providing proper context.

As we saw in Independent Documentary Photography, Chinese photographers in the 1980s responded to their newfound, post-Mao artistic freedoms by using the camera as a truth-seeking witness, recording “real life” in China at the ground level. That all came to a screeching halt after 1989’s Tiananmen Square massacre, which led to a government ban on avant-garde art. Just as quickly as the New Wave had sprung up a few years prior, unofficial photography was suppressed. Half a decade later, New Photo was one of the chief instruments to awaken and revitalize the form.

The subversive magazine called on photographers to move beyond documentary modes, pushing them toward more conceptual inquiries and subjective expression. The pages of New Photo (which have been recently reissued) both provoked and recorded China’s first wave of experimental and idea-driven photography. Vine Street’s spotlighting of 16 photographers from New Photo occasionally reveals technical shortcomings or an awkward self-consciousness, but since these were literally among the first experimental photographs the country ever produced, it would take a heartless viewer not to forgive their superficial shortcomings.

Some of the strongest works include Zhuang Hui’s grids of self portraits, taken with total strangers. Formally reminiscent of 1960s American conceptual art, the individual images blandly depict Zhuang posing with a deadpan rigidity in the company of artists, workers and children. Even though only two figures appear in each photo, they seem generic and anonymous, due to the multiplicity of images and Zhuang’s impersonal artistic treatment. The artist spoofs China’s strict social classifications with titles such as “One and Thirty Workers,” as well as the Communist fetishization of collectivism. FotoFest’s show of Cultural Revolution propaganda didn’t contain a single image of a solitary figure; Zhuang mocks the efficacy of such communal idealism in these witty pieces.

Liu Zheng’s sepia tableaux from the Breaking the Princess series are less cerebral but more sensual. In a visual style reminiscent of Joel Peter Witkin, four striking, nude women enact an unfamiliar parable of tangled webs, deceit and “White Bone Demons.” The signifiers are lost on me, but Liu’s art direction, intricate costuming and evocative stylization are superb.

Additionally, An Hong’s self portraits as sexualized, gender-bending Buddha warriors, Hong Lei’s mournful, symbolic still-lifes, and Zheng Guogu’s participatory snapshots of adolescent gunplay and rebellious anger all stand out for their daring breaks with convention and political defiance. Because most of these pieces are only a decade old, their tremendous historical importance is difficult to fully grasp, and the artists’ conceptual innovations and social risk are nothing short of inspiring.

Moving beyond the New Photo era, FotoFest’s contemporary artists are curatorially grouped at four additional venues. Work by four artists at Williams Tower, unified by historical critiques and revisions, proved most impressive. Two artists in the show make work based on traditional Chinese painting, both producing circular images. In Wu Gaozhong’s wonderful Rotten Organic Compound landscapes, putrid mold colonies become tranquil, otherworldly hilltop scenes. Meanwhile Yao Lu recreates iconic classical paintings in Photoshop. Misty mountaintops and village fishermen have been replaced by industrial litter and hardhatted contractors. The photographs are elegies to the traditional values and vistas currently being eradicated throughout China in the name of capitalist progress.

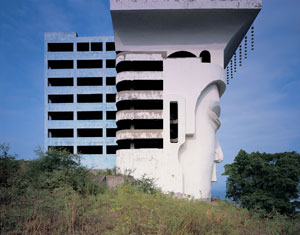

Two artists at Bering and James directly address the country’s radical modernization. Zeng Han’s photographs of developments and diversions in the urban landscape beg to be collected in book form. As China grows at an astonishing pace, marvelous (and marvelously kitschy) structures are abandoned as quickly as new ones are built. Las Vegas has little on Beijing’s cheesy simulacra, which include overgrown theme parks and half-constructed Roman villas. In an era packed with color photographs exploring diametrical relationships between man and land, Zeng’s remarkable vistas are full of surprise and visual richness.

Work by his gallerymate, Xing Danwen, doesn’t fare so well, conceptually or formally. Similarly attuned to China’s hypermodernization, Xing shoots architectural models of massive developments and skyscrapers. She then digitally inserts humans into the faux-buildings, alternately updating Edward Hopper’s lonely alienation or creating Hitchcockian narratives.

Aside from the rather banal play on artifice and scale, Xing’s work is held back by the same problem that plagues roughly half of the contemporary artists on view – her Photoshop work is crude to the point of distraction. In addition to Xing’s work, most of the artists’ prints were also produced by FotoFest sponsor Hewlett-Packard. On top of the artists’ Photoshop issues, HP’s printing technology produces some odd chromatic shifts.

At the Art League Houston, three contemporary female artists address China’s archaic gender roles. Sun Goujuan documents her aging process through annual nude self-portraits, taken after she literally sugarcoats her body. This is presumably a remarkable gesture in China, where the expression, “As China gets richer, women should get prettier!” is bandied about. But while the photographs may be seen as a bold act in China, they aren’t especially intriguing. They are better appreciated here as documents of Chinese feminism.

Chen Lingyang takes the corny art school impulse of vaginal self-portraiture and turns it into something interesting with her rice paper scroll, Twelve Flower Months. In beautifully crafted still-lifes, hand mirrors capture reflected glimpses of Chen’s menstrual cycles—a gesture saved only by the artist’s impressive aesthetic handling. When the work was first exhibited in Beijing seven years ago, the government shut the exhibition down. Noting that the photos would have been deemed acceptable if the genitals had been digitally blurred, Chen reprinted the work, adding defiantly unsubtle pixel matrixes to her crotch shots. Both versions of the scroll are included here, and are considered landmarks of feminist art in China.

Liu Lijie, the youngest of the three female artists, photographs herself in staged, narrative tableaux, which she then digitally sanitizes with the shadow-free post-naturalism of Loretta Lux. The scenes often find the artist in the company of an older Chinese man, who is evidently happy to use her sexually, but doesn’t seem interested in making eye contact. Liu presents herself as a vacant entity as well, preoccupied and distant as she undresses for him. The images are much more developed than a previous series of fairy tale self portraits included in a book of the artist’s work. They signal an assimilation of Western visual tropes, but still feel like the work of a young, developing artist.

The female perspectives found in the Art League show—visual protests from women who celebrated their bodies and also detached from them in the face of patriarchal oppression—stuck with me as I took in Cang Xin’s staged, quasi-pagan performance photos at the New World Museum. Visually stunning, Cang’s color murals depict the artist on the Mongolian plains, often with dozens of other men. They participate in faux-tribal performances, which often involve torches, rings of fire and male nudity. Cang is interested in reclaiming ancient Chinese philosophies and shamanistic rituals. In his Man and Sky as One photos he leads men to submerge themselves in riverbeds and pose (via the magic of Photoshop, it sometimes appears) inside flaming circles of grass. The ponytailed artist comes off as something of a macho cult leader, though, more interested in male bonding and visual dynamics than humble commune with the spirit of nature. The exclusion of women from Cang’s agenda makes his smoky scenes of shirtless torch-waving look like some Mongolian version of the Promise Keepers.

“Troubling” and “unsettling” are apt descriptors for contemporary China. Aside from Wu Jialin’s idyllic village scenes, every photographer in FotoFest this year contends with or confronts social conflict. Even Zhuang Xueben’s gorgeous images of noble Tibetans were born of colonialist, ethnographic intentions and military invasions. Sha Fei’s anti-Japanese fanaticism gave way to the Cultural Revolution’s propagandist imagery. From there, artists have struggled to address the stranglehold on free thought that gripped and stunted generations of Chinese citizens. With every tentative advance, it seemed, the state forestalled progress, except when it meant mass financial gain. The country’s current rampant money grab has created an entirely new set of problems (one of which is thoroughly explored at Houston Center for Photography’s Mined in China). The artists who presently grapple with these complexities operate within a system that views censorship and totalitarian information control as the norm. (One of the FotoFest artists was denied permission to travel to Houston, as her unwed, low-income social status was perceived as a flight risk. And one has to wonder how permissive the government would have been about sending these photographs off if China’s current publicity nightmare had taken place a few months prior.)

On top of it all, contemporary Chinese photographers have no modern artistic tradition to build on and few historical mentors to provide guidance. Within their own culture, they are the pioneers of the transgressive avant-garde. So when Cang Xin’s spiritual and artistic thirst leads him to a cheesy situation with nude men on a remote mountaintop, and when Yao Lu’s collaged landscapes suffer poor pixel-blending, one would have to be drastically shortsighted not to look beyond the imperfection.

FotoFest’s story of modern Chinese photography is filled with tales of political and artistic risk. Artists were firebombed, left for dead in unmapped territory, worked under the official supervision of a tyrannical dictator, had their exhibits shut down and risked arrest in order to publish conceptual photography. These remarkable stories yielded scores of even more remarkable photographs. The opportunity to view them is nothing less than a privilege.

Chas Bowie is a writer in Portland, Oregon. He has published in Art Papers, Tokion, Anthem, the Photo Review

and many other art and culture magazines. He was one of Glasstire’s

first writers, as well as the Exhibitions and Publications Coordinator

for FotoFest 2000.

Read FotoFest 2008: Photography from China, 1934-2008, Part 1 and FotoFest 2008: Photography from China, 1934-2008, Part 2 by Chas Bowie