I don’t know Bruce Nauman, but I have spent long and productive hours getting to know him in absentia via the many poses he strikes in his sculptures, videos, drawings, and installations. “The true artist is an amazing luminous fountain” is one of Nauman’s most enduring aphorisms, and this show portrays him as a fountain that spurts in many directions. Occasionally he succeeds in making only a mess; more often than not his artistic displays are sparklingly luminous provocations.

Dominique and John de Menil did not make Nauman one of their artistic focal points: only one work — a 1965 rubber and burlap piece — was purchased by Walter Hopps for the Menil’s permanent collection. However, “Bruce Nauman: A Rose Has No Teeth” is perfectly situated in the Menil’s galleries. Organized by Constance Lewallen for the UC Berkeley Museum of Art, the exhibition opens with works from 1964, the year Nauman began his graduate studies in the art department of the University of California, Davis. By the time of his first New York gallery show at Castelli Gallery in 1968, Nauman had outlined all the areas of interest — cast sculpture, neon word games, body manipulations, performative video musings, architecturally inflected installations — that continue to form his artistic core. Focusing as it does on the period during and immediately after Nauman’s graduate school experience, this survey offers a profoundly revealing case study of the process of becoming. More importantly, it is also a surprisingly intimate portrait of an artist who has devoted his entire career to pioneering “personal/impersonal” as an artistic stance.

“A Rose Has No Teeth” is also is a study in restless experimentation, full of sudden shifts in media, approach, and content. Nauman came to Davis as a painter, but quickly abandoned paint for experiments in sculpture and film. The exhibition begins with a sampling of these graduate school works. Wall-mounted fiberglass forms, made between 1965 and 1966, are highly crafted, retaining in their subtle coloration vestiges of his interest in painting. Cardboard sculptures come across as model-like sketches while his unglazed ceramic cup forms possess a vigorous crudeness that must have irked Robert Arneson, for whom Nauman worked as a teaching assistant.

Infrared Outtakes: Neck Pull...(photographed by Jack Fulton)...1968/2006...Epson UltraChrome K3 inkjet print...20 x 28 inches...University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive...gift of the artist and Gemini G.E.L. LLC. ...© 2006 Bruce Nauman/ARS, New York.

Nauman shot two films in 1965, and despite their rudimentary execution they make a compelling diptych. Manipulating the T-Bar (1965) shows the artist delineating what would become his basic studio practice, arranging and rearranging a sculptural form within the constrained architectural parameters of the studio. Film of an actor pretending to be myself making a tape of the sound effects for the film “Manipulating the T-Bar,” on the other hand, introduces what would become Nauman’s consistent artistic persona: the absent presence.

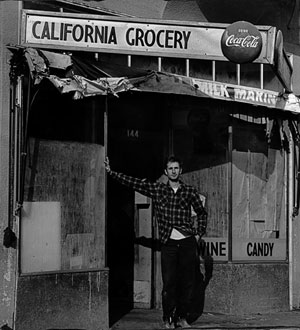

Nauman had his first gallery show with Nicholas Wilder in Los Angeles shortly before graduating in 1966. “Mold,” “device,” “shelf,” and “platform” are the first words of several of the artwork titles, reinforcing Nauman’s minimalist-inflected preoccupation with cast or constructed form. The LA show was a marginal success. Living off a part-time teaching job, Nauman set up shop in a cheap San Francisco storefront. There he continued the artistic relationship (equal parts mentorship and collaboration) he had established with his former teacher William T. Wiley, and spent a lot of time in his studio working with whatever was at hand — mostly, his own body. Nauman outlined his post-graduate plan of attack in a short list:

Codification

1. Personal Appearance and skin

2. Gestures

3. Ordinary actions such as those concerned with eating and drinking

4. Traces of activity such as footprints and material objects

5. Simple sounds — spoken and written words

Metacommunication messages

Feedback

Analogic and digital codification

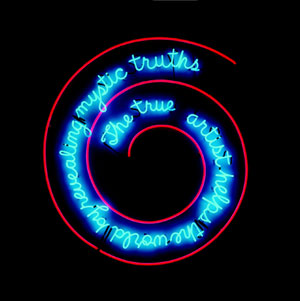

“A Rose Has No Teeth” hits the accelerator pedal here, proving once again that some artists are better off being poor and alone in their studio. Nauman careened through 1967 in often dizzying directions, casting parts of himself to illustrate verbal truisms (From Hand to Mouth), staging himself in punning, banal, or situational poses for color photographs (Waxing Hot; Coffee Thrown Away Because It Was Too Cold; Finger Touch With Mirrors), exaggerating his sense of self (Six Inches of My Knee Extended to Six Feet), or illustrating slogans in neon (The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths).

Self-Portrait as a Fountain (from the portfolio Eleven Color Photographs)...1966–67/1970...chromogenic development print...19-7/8 x 23-3/4 inches... collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago...Gerald S. Elliott Collection...Photo: Michael Tropea...© MCA, Chicago. © 2006 Bruce Nauman/ARS, New York.

Most provocatively, Nauman continued making 16 mm films that treated his body as a piece of sculpture. Using color, he changes his appearance (Art Make-Up) or kneads his upper leg like a piece of clay (Thighing). Working in black and white, he records constructed situations that are balletic (Dance or Exercise on the Perimeter of a Square), comedic (Walking in an Exaggerated Manner Around the Perimeter of a Square), or calculated to transform 10 minutes into an eternity (Playing a Note on the Violin While I Walk Around the Studio). Sound is a component of many of these videos, and their cumulative effect injects a hissing, thumping, and clanging sound collage into the Menil’s normally staid galleries.

Hannah Arendt used words to describe the banality of evil; a large part of what any visual art records is the banality of creativity. Or, as Nauman famously said, “Art is what an artist does, just sitting around the studio.” But for Nauman studio-sitting is never a passive activity, a way to pass time in the hope of generating aesthetically pleasing dust bunnies. For better and worse, his studio practice reflects the sensibilities of an inventor preoccupied not by product creation but by investigations of theater (Beckett) and philosophy (the exhibition’s title is derived from a lead plaque Nauman made that directly quotes Wittgenstein’s systematic deconstruction of the phrase “The law has no teeth.”). Two 1968 installations codify Nauman’s increasing penchant for categorizing himself in neither/nor terms while expressing his relationship with the viewer in terms that illustrate the Nietzschean aphorism “Human, all too human.”

The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths...(Window or Wall Sign)...1967...neon tubing with clear glass tubing suspension frame...59 x 55 x 2 inches...artist’s proof...collection of the artist...courtesy of Sperone Westwater, New York...© 2006 Bruce Nauman/ARS, New York

The sound installation Get Out of My Mind, Get Out of This Room defines an invisible self in terms of an otherwise aesthetically neutral space. Nauman growls, hisses and grunts the work’s title over and over from two speakers mounted opposite each other in a closet-sized enclosure, effectively terrorizing those who wish to experience his sonic component that the Menil staff should turn this artwork into a competitive time trial endurance event, with the exhibition’s catalogue as a prize.

On the other hand, the pairing of the video Walk with Contrapposto with the video’s sculptural element, Performance Corridor, shows Nauman at his vaudevillian best, merging the wry sense of humor that permeates many of his best works with a pose capable of encompassing classical and contemporary sculptural attitudes. Watching Nauman bump and grind his way down the confines of his Performance Corridor you may be tempted, as I did, to reenact his performance yourself. As you become the performer, you find the calculated impersonality of Nauman’s bodily gestures relocating themselves within your own identity like a virus, or a second skin.

“Bruce Nauman: A Rose Has No Teeth,” remains on view at the Menil Collection through January 13, 2008.

Christopher French is an artist and writer currently living in Houston.