I own three art dictionaries, references published in the late 1980s by such reputable houses as Thames and Hudson, Penguin and Random House. Each has been rendered largely useless by Internet-based databases, but I keep these relics because they help me remember what the art world used to look like. My college education ended the same year Hélio Oiticica (1937-1980) died.

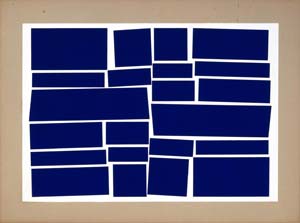

Hélio Oiticica...Glass Bólide 05 “Homenagem a Mondrian”...1965...Oil with polyvinyl acetate emulsion...on nylon mesh and burlap; glass;...paint and pigment suspended in water...César and Claudio Oiticica Collection...

Like my outdated reference books, my well-informed, able teachers never mentioned his name, even though they grounded me well in the art of his North American contemporaries. Omissions like this capture a moment in time when many Latin American artists were simply not considered noteworthy in an art world still largely coordinated along a New York- Europe axis.

Times have changed, and Hélio Oiticica: The Body of Color at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, provides compelling evidence for why this artist has gained in stature only since his death. Exhibition curator Mari Carmen Ramírez describes Oiticicia's creative persona as occupying a complicated place where "a poète maudit coexisted with a methodological intellectual, intuitive researcher, and consummate artistic practitioner." Reflecting this schism in its layout, the exhibition reads like a tale of two careers. Its first part, consisting of serial processions of small to medium sized paintings dating from the 1950s, is subdivided into room-like chambers. For the remainder, walls largely disappear, and Oiticica's increasingly sculptural assemblages sprawl across the open vistas of the Law Building's second floor galleries.

Many artists struggle against the grand sweep of Mies van der Rohe's lateral curve, but it suits Oiticica well. Perhaps this is because after 1960, when he increasingly turned from painting to sculpture, he was chasing art toward architecture, interactivity and conceptualism: he began as a dedicated modernist and ended up experimenting with the dynamics of human interaction. The first works in The Body of Color date from 1955 and show the influence of late Piet Mondrian and Paul Klee on the largely self-taught 18-year-old. Unlike these modernist pioneers, Oiticica experienced no breakthrough from representation to abstraction — from the outset his paintings structure austere geometries into assertively nonrepresentational color arrangements dominated by one or two colors. Throughout the 1950s the syncopated modulations of his gouache-on-cardboard compositions are largely tonal and firmly non-associative. Like Ad Reinhardt, Oiticica excelled at framing progressions of closely related colors to negate suggestions of locale, materiality or identity. The spaces that his art proclaims are resolutely internalized and geometrically precise, and they epitomize the post-World War II optimism that pervaded International Style abstraction.

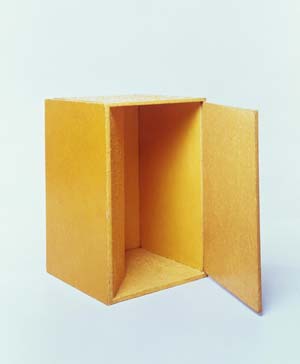

Hélio Oiticica...Box Bólide 01 “Cartesiano...1963...Distemper with polyvinyl acetate emulsion on plywood...César and Claudio Oiticica Collection

In this sense Oiticica was very much in synch with Brazil's idealistic dedication to the perfectibility of humanity through geometry, which was embodied in the mid-1950s creation of Brasilia, a new capital city constructed in the nation's center by urban planner Lúcio Costa, architect Oscar Niemeyer and landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx. Oiticica's close friend and sometime collaborator Lygia Clark had studied with Burle Marx, and Oiticica may have become interested in translating painting into sculpture through her. More likely, he gleaned it from his associations with brief-lived Brazilian artistic movements like Neo-Concreto and Grupo Frente. A dedicated polemicist throughout his life, Oiticica enunciated ideas about color, space and social utility in manifestos and articles like "Color, Time, and Structure" (1960) and "Releasing Painting Into Space" (1962).

In 1959 we see his painting veer in contrasting directions. A series of all-white paintings segues into shaped canvases whose ochre, brown and earthen gray tones use modulating, right-angle brush strokes to capture light. These give way the following year to Spatial Reliefs, freestanding paintings that propose what the artist called "hanging time." Oiticica's paintings are pregnant with possibility, and the new decade's onset was his breakout period. He initiated a vast expansion in the scale and scope of his painting in the Nuclei Series (1960-1969), which structures shades of a predominant color around free-floating architectural clusters of right-angled panels. Oiticica's 1961 proposal for a park, Maqueta para Projeto Cães de Caça [Maquette for Hunting Dogs Project], shows him intent on using geometry to shape nature, a preoccupation that prefigures the landscape interventions of Michael Heizer and Robert Smithson.

After 1960 Oiticica increasingly juxtaposed unorthodox combinations of nontraditional art materials in small, freestanding painted assemblages. Bólide means "fireball" in Portuguese, and color in this series is largely limited to sunny yellows and fireplace oranges and reds. Early versions are constructed from wood. Painted one or two colors, they are contemporaneous with, and similar in spirit to, Donald Judd's early painted sculpture. While Judd quickly turned the manufacture of his machined geometries over to fabricators, Oiticica's aesthetic remained insistently hands-on. He described the Bólides as "laboratories for color," and the 30 examples on display certainly privilege questioning above answering. Conflating decoration and utility, they increasingly feature a wide range of manmade (fabric, mirror, plastic) and natural (shell, stone, earth) materials as basic building blocks.

Like Robert Rauschenberg, Oiticica wanted art to acknowledge that "looking also happens in time," but he was after something different than the referential, largely pictorial specificity of Rauschenberg's silkscreened image appropriations. Oiticica's work begins and ends in abstraction, but it insists on creating spaces allowing people to interact with it. In response to the social tumult that Brazil experienced throughout the 1960s, Oiticica turned away from pure geometries and toward popular culture. In 1967 he coined Tropicália to describe his work's outlook, a term that Brazilian musicians subsequently adapted into Tropicalismo. When he displayed a poster bearing the slogan 'seja Marginal, Seja Herói" at a 1968 Caetano Veloso concert, it was confiscated by the police and the concert was shut down. The exhibition catalogue translates this phrase as "Be an outlaw, be a hero," but whether you say outlaw, outcast, or outsider, Oiticica's advocacy of heroic creativity through Spartan marginality translates easily, capturing the crossbreeding of artistic and political ferment in late-60s Brazil. Yet societal edginess always has its downside: the fragility of the materials Oiticica chose to work with, coupled with his studious neglect of his finished artworks, has meant that nearly half of the 220-plus works presented in The Body of Color needed to be restored for this show.

Hélio Oiticica...Relevo especial (vermelho)...1960...Polyvinyl acetate resin on plywood...César and Claudio Oiticica Collection

In 1964 Oiticica spotted a beggar's wooden construction in a slum bearing the phrase "here and…Parangolé," which he adopted as the title for his Parangolés series (1964-1968). Oiticica intended his wearable art, which he described as "body filters," to be activated by a dancer. A half dozen are installed on the MFAH's walls like paintings; nearby is a rack full of replicant Parangolés for the occasional live performances that will punctuate the show. Pointedly decorative as inanimate objects, they are juxtaposed with three large-screen projections that show Parangolé -clad dancers bringing Oiticica's "paintings" to life. The video's subtitled translation of the artist's narration ably documents how much the artist preferred questioning to answering: "If it is an invention, I am not able to know it…. If I knew what these things were, they would no longer be an invention."

Oiticica did not simply disappear into Rio's slums. A survey of his work was held in London's Whitechapel Gallery in 1968, then armed with a Guggenheim grant, he left Brazil's political repressions for a wide-open New York in 1970. There he experimented with ephemeral works composed of store-bought items (Topological Ready-Made Landscapes) and film fragments (Quasi-cinemas). He returned to Rio in 1978; two years later he suffered the massive stroke that killed him. Color is certainly an appealing aspect of Oiticica's art, but it is the restless spirit of experimentation that pervades the The Body of Color and that makes this exhibition such a refreshing antidote to the art world's current constrained sensibilities.

Hélio Oiticica: The Body of Color remains at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, through April 1. The exhibition travels to the Tate Modern, London, June 7-September 23.

Images courtesy MFAH.

Christopher French is an artist and writer living in Houston. French has an upcoming solo show at Holly Johnson Gallery.