"Affection beaming in one eye and calculation shining out of the other."

Charles Dickens, 1844

Uncovering a bright new talent isn't always as gratifying as revisiting an established discoverer. The latter approach brings the works of Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide out of the archives and into the public sphere. The iconic images of Angel Woman and Lady of the Iguanas take their places as bookmarks in this retrospective, but visitors should look beyond these familiar images. True to the gravitas of her Mexican roots, Iturbide delivers a documentation of death that eludes the openness of photojournalism and nests instead somewhere in the crackling brambles of covert observation.

There is a parallel between Iturbide's black and white approach and the work of artists such as Diane Arbus, Weegee and Brassai. She captures portraits with a piercing intensity. Her execution, as well as her ability to convey internal reflection in her skewed self-portraits, makes it easy to draw immediate correlations to the brutally honest portraiture of Arbus as well as the criminal content of photographs by New York City shutterbug Weegee.

Promoted as "one of Mexico's great photographers," Iturbide has filled the Wittliff Gallery of Southwestern & Mexican Photography in San Marcos with poignant and illuminating photos that give viewers a sense of nonpareil intensity. (As a side note, the Wittliff Gallery holds the largest archive of Iturbide's work in America. So even if you miss the current exhibit, you can still seek out her work through the archives.)

A photo taken in Juchitan, Mexico, captures a corpulent, nude woman preparing to take a bath, perched atop a white toilet. The Bath pulls viewers into a scene where the clandestine is manifested and observation skirts voyeurism. In Cholas II, the photographer perfected the art of portraiture by documenting the criminal pride of women impervious to anything outside of their subculture. Their hands form a cryptic alliance with something so sinister when viewed in the California sunshine that the image could be construed as a type of collusion.

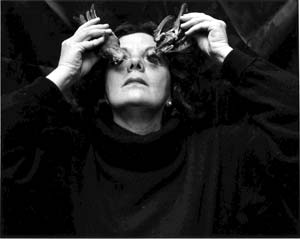

Iturbide won a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1988. You can see her combined determination and introversion in her Self Portrait series. In the title image, Eyes to Fly With, she holds two desiccated pigeon carcasses against her closed eyes, one pearl earring acting as a glint of hope amidst the macabre flight interrupted. Her chosen background of squid-ink black satin sheets with barely discernible floral patterns makes this self-reflection seem like the photographer's attempt to cozen death into dialogue. Her Self Portrait taken in Coyoacan, Mexico, curiously enough has a counterpart in the recent retrospective of experimental composer and theatrical visionary Carles Santos. On display at the Fundacio Joan Miro in Barcelona, one of Santos" photographs features an equally intriguing portrait of a woman covered in snails, sans mucus. In Iturbide's work, the circuitous trails of mucilaginous disgust along her black sweater remind us of lives left behind. Her expression is that of a catatonic, glassy-eyed vagabond, perhaps in the quietude between speaking in tongues. The six slugs fixed on her face seem to have been coaxed from their hardened shells only to become as vulnerable as their muse. It's an image easily dismissed as completely daft, but somehow the more you consider it, the more it accrues pulchritude.

This is the first time a series called Death in the Cemetery has ever been shown in a public space. Indeed, these are the photos that will have you sifting through the nightmarish images filed in your own personal mental archive long after you've left the library. Gallows humor rears its Darth Vader head (literally) in a strange storefront window in Chiapas with a sign that reads “¡Mexico … quiero conocerte! [Mexico … I want to get to know you!].” Two of the most riveting photos on display are Bombay and Death in the Cemetery .

In this exhibition, Iturbide's Iturbide has taken neglected corners of a fascinating country and presented them with the same lucid sense of both affection and calculation that Dickens described in 1844.

Images courtesy Wittliff Gallery

Michelle Gonzalez-Valdez is an artist and writer from San Antonio.