Druecke’s work springs from the forlorn and forgotten: photographs relegated to that shoe box under your bed; the seldom occupied picnic table in a grassy lot not quite big enough to be a park; everyday moments that barely register in your stories of what you did that day.

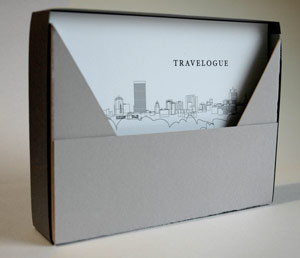

Of all the work Paul Druecke has shown in the last few months, my favorite piece is the only one that wasn’t exhibited somewhere in Houston. Travelogue (2004) debuted in September at the Jody Monroe Gallery in Milwaukee, the artist’s hometown. This was appropriate, since Druecke’s fourth self-published book recounts his travels in The Genuine American City. The book is comprised of twenty note cards, each of which includes a photograph on one side, and a dated journal entry on the other. Part meditation, part diary, Travelogue charts some of Druecke’s past projects, as well as his everyday movements through the city: the alley behind his house, the empty patch of cement he passes by on the way to work, the glowing night-time windows he enjoys while walking at night. The scenes captured in Travelogue are almost uniformly devoid of people, highlighting each detail of otherwise banal pictures. Separated from its immediate context, an old brick building or a low cement bridge becomes mysterious and impenetrable, alien and strange, like a tool whose function has been forgotten, but which remains, nevertheless, a beautiful object. Druecke’s enigmatic snapshots of Milwaukee are paralleled in his writing. Entries begin with a description of one of his haunts, then spin out into a web of marginalia, from the final days of the dinosaurs to the distance from Milwaukee to the Atlantic Ocean — exactly the kind of thing you might hope to discuss during a leisurely ramble on foot through the city.

Druecke’s work springs from the forlorn and forgotten: photographs relegated to that shoe box under your bed; the seldom occupied picnic table in a grassy lot not quite big enough to be a park; everyday moments that barely register in your stories of what you did that day. Through his projects, Druecke temporarily transforms these fragments of the everyday into something else; by changing the context, he shifts their meaning. This transformation is often realized through direct intervention. Blue Dress Park (2000) was inspired by one of his favorite forgotten spaces in Milwaukee, a deserted plot of cement that had been incomprehensibly cordoned off by a low fence. Druecke’s description of this site in Travelogue reveals that its unintelligibility is precisely what drew him to it: “This is urban design gone awry — extra space separated from the world in the shape of half a teardrop. This place is useless, and invisible for its lack of integrity. Maybe it could be special, but it’s not. Still, it managed to eat through layer after layer of my unawareness. I love this patch of cement.”[1] Indeed, Druecke loved it so much that he made it special by designating the site “Blue Dress Park.” In the summer of 2000, Druecke sent out invitations to a christening celebration, temporarily converting a forgotten corner of the city into a crowded meeting place, every urban planner’s dream.

Paul Druecke...Invitation to Blue Dress Park Christening Celebration...2000...public event...photo: Peter DiAntoni

In January 2005, Druecke hosted a similar event in Houston, when he designated the Museum of Contemporary Art’s west lawn the “Community Courtyard.” Located behind the museum building, this space might be familiar if you’ve ever noticed the artwork installed there: Mel Chin’s Manila Palm: An Oasis Secret (1978), a 50’ tall sculpture made up of an artificial palm tree growing out of a pyramid. Chin’s sculpture was left in the dark for Community Courtyard. Instead, Druecke lit a group of tall trees at a corner of the lot, green even in winter and redolent with beautiful red berries — thereby composing a picturesque view that might as well be a photograph from Travelogue. About thirty people braved the cold to christen the Community Courtyard with a champagne toast and to pick up a free t-shirt. Druecke asked for contributions of $10 prior to the event, which paid for the production of the t-shirts that commemorate the Community Courtyard and feature a list of sponsors.

Though Druecke designates his impromptu parks, these projects rely on the participation of others for their success. Much of the artist’s work incorporates individual action by collaborators as part of its content. Collaboration was the premise behind Amalgama, a group exhibition at Houston’s Contemporary Arts Museum (number 144 in the CAM’s Perspectives exhibition series). Community Courtyard was held in conjunction with the show, which featured a number of one-night events hosted by artists included in the exhibition. Curators Paola Morsiani and Paula Newton presented a group of photographs from Druecke’s series Between Sleep and Awake (2003-2004) in Amalgama (part of the series was also on view early this winter at Inman Gallery).

For Between Sleep and Awake, Druecke set up his camera at the bedside of his collaborators, 25 acquaintances or strangers from Milwaukee. He asked each participant to press the camera’s cable release when they first awoke, in that hazy moment between being asleep and fully conscious. The artist was not present when the photographs were taken. Druecke cropped the resultant pictures so as to eliminate as much of each room’s details as possible, leaving a grainy close-up image of the bleary-eyed sleeper that is printed close to life-size on matte paper. In each exhibition, the photographs lined a rectangular gallery, unframed and mounted to the wall with pushpins.

Paul Druecke...Community Courtyard christening celebration...2005...Public event, dimensions variable...Photo courtesy of the artist...

For Druecke, the moment this series captures is mundane but ultimately significant — the transition from a dream state to consciousness is “the fleeting bridge between our two modes of existence.”[2] Intimately familiar to us all, it proves nearly impossible to really remember the moment one wakes up. Looking at the photographs, I can feel how groggy the subjects are, and wonder if they even recall taking these pictures. Most of the subjects are washed in bright, early morning sunlight. A few look directly at the camera, but the person I most identify with, Stephanie, has a face covered with tangled hair and parted lips that hint at a drool-dampened pillow. These self-portraits are about as close as you can get to taking a snapshot of yourself unselfconscious and not posed. By presenting the photographs in a series, Druecke reminds us that though the instant we first awake is extremely private, each of us has this same experience every day.

If collaboration is Druecke’s mode of operation, then the snapshot is his medium. Druecke uses the ubiquity of the camera as a way to create a space for other individuals in his working process. The loose sets of instructions he gives his collaborators provide a framework that leaves much up to chance. Druecke began this line of inquiry in 1997, when he established A Social Event Archive. Through door-to-door solicitation, a flyer campaign, and help from friends and family, Druecke invited individuals to contribute one snapshot photograph to the archive. The only stipulation was that each snapshot document a social event. The photographs were gathered in the order received and presented back to the public, first through a comprehensive website, and later in traveling exhibitions of selected snapshots from the archive and, to date, three limited-edition books. The archive currently includes more than 700 photographs, which show everything from birthdays to vacations, graduation ceremonies, weddings, and backyard parties, as well as some less conventional social events — a group of smiling, orange-clad hunters; the after-math of a church fire; a woman blanketed in stuffed animals. At flea markets and rummage sales, I often find myself drawn to the saddest items on offer — shoe boxes full of photographs that have somehow found their way to the ten-cent table. Druecke’s project doesn’t so much rescue these photographs (he isn’t trolling yard sales for funny pictures), as it recovers the meaning embedded in snapshots once the stories associated with them have been lost.

Druecke’s most recent snapshot project, A Public Space – Main Street Square (2004), further exploits our obsession with photography. 24 12” x 16” photographs line the walls of a house at Project Row Houses for the 21st round of artists’ installations. Walking past the pictures, it soon becomes apparent that they are all photographs of the same place, taken by different people. Druecke invited one person to take a photograph of Main Street Square in downtown Houston, a recently developed area that includes a stop on the new rail line and a fountain. This individual chose the next photographer, who took a single photograph of the same place, and then picked another photographer. A key accompanies the photographs, which identifies the photographers as well as their occupations.

Paul Druecke...Between Sleep and Awake...2003-2004...Archival ink jet prints...22 x 28 inches each......Installation view at the CAM...(l-r): Daisy C., Michael F., Madeline L.

Each photograph represents an individual point of view and sensibility. Standing on a busy downtown street corner, we might each notice different details from our surroundings, and record whatever catches our eye. Druecke’s process for choosing his collaborators allows these differences to manifest themselves. Participants were free to photograph whatever they wanted within a circumscribed area. What becomes important in Main Street Square isn’t so much the differences between the photographs, as the social network they describe. In his essay for the exhibition brochure, anthropologist Christopher Kelty compares the web of relationships formed by the participants to the famous “six degrees of separation” experiment conducted in the late 1960s by social psychologist Stanley Milgram.[3] Milgram instructed a randomly selected group of individuals in a rural Nebraska community to send a postcard to a particular stockbroker in Boston. They could only accomplish this by sending postcards to friends or relatives, and Milgram found that, on average, it took six postcards to get from Nebraska to Boston. Therefore each of us is connected by only six degrees of separation. Looking at the photographs in Main Street Square, we might imagine ourselves linked to these photographers through a similarly small chain of individuals. In this way, Druecke’s project describes a particular location, as well as a community.

Community lingers in the background of all of Druecke’s work. In fact, we might say Paul Druecke is a community artist. Not in a mushy, feel-good way that might result in community center murals or some variety of Cows on Parade. The concept of community at work in Druecke’s projects centers on shared experiences that connect us to each other in ways that are often surprising, and frequently ignored. Paradoxically, these experiences are more often than not tremendously private; they are shared out of the goodwill of individuals. According to the artist, his projects allow a tension to arise “between individual identity and a larger social fabric” by way of the input of his collaborators.[4] Rather than leveling out the larger collective field through generalization, he relies on individual participation to describe who and what make up a community, and also to hint at the elasticity of these limits. Community is sometimes defined by a specific place, as in Main Street Square, or a specific event, like Community Courtyard. In other cases, the connection between a group of people is much more general — the familiar snapshots, taken by strangers, that make up A Social Event Archive; the universal experience of being between sleep and awake. With all of these projects, what we hold in common can end up feeling somewhat alien, but perhaps this is because the things Druecke draws attention to are so often overlooked.

1. Paul Druecke, “Entry 8-04-99,” in Travelogue. Art Street Window, 2004. Edition of Fifty.

2. Paul Druecke, “Letter of invitation to the first participant,” in Amalgama. Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, 2004. p. 6.

3. Christopher Kelty, “A Public Space; Main Street Square,” in Paul Druecke, Round 21 exhibition brochure. Project Row Houses, 2004.

4. Druecke, Artist Statement, Inman Gallery, 2004.

Images courtesy the artist and the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston.

Amanda Douberley is a graduate student in Art History at UT Austin, and a 2004-2005 Critical Studies Fellow at the CORE Program in Houston.