Sometimes the best test of an artist’s work is how well it translates into a foreign setting. Visiting Paris recently, I had the opportunity to see how well works by five San Antonio artists stood up to foreign scrutiny, and to compare them with other exhibitions exploring similar themes.

Galerie praz-delavallade, site of Dario Robleto’s Diary of a Resurrectionist, is one of several spaces that followed the Bibliothèque Nationale to the 13th arrondissement after it gave up its historical digs for a modernist façade outside the city center. Diary shows Robleto at his audacious best, building on his 2003 Inman Gallery show (Roses in the Hospital/Men Are the New Women), his presentation in this year’s Whitney Biennial, and his related concurrent exhibition, Southern Bacteria, at Acme Gallery in Los Angeles. Robleto continues to make strongly emotional sculptural statements by holding the mirror to reality. Fashioning faux-historical objects from obscure materials, he attracts free associations like moths to a flame.

Robleto’s history-laden materials (ground trinitite from atomic test sites, a daguerreotype, and a civil war-era inkwell are among the many things that comprise the show’s title sculpture) conflate themes of disease and rehabilitation with salvation and loss. The artist makes this explicit by alternating medicinal titles (Fatalism Sutures to a Memory; An Atheist as Described by a Surgeon) with religious references (A Color God Never Made; The Gospel of Lead). His complicated materials lists always make fascinating reading, and the gallery printed them large and displayed them prominently on one wall. They also emphasize the predominantly American origins of his sculptures. The universality of his themes, on the other hand, was evoked by the gallery’s proximity to Hôpital de la Salpêtrière, a walled compound designated in the 17th century by Louis XIV as hospice for Paris’s 30,000 tramps. It later evolved into Paris’s largest hospital, whose most famous resident was perhaps Manon Lescaut, of novelistic and operatic fame. This context meshed comfortably with the redolent historicity of Robleto’s art, suggesting an installation by proxy. In any case the sold-out show was proof that the French had no problem either translation or appreciating Robleto’s point, especially since they coined bricolage, the term for the handyman’s practice of fixing things with what is at hand.

If galerie praz-delavallade’s white-cube spaces purposefully state atemporal neutrality, the Chapelle Saint-Louis de la Salpêtrière oozes history. Located walking distance from praz-delavallade in the heart of the Salpêtrière compound, the chapel has hosted installations by artists ranging from Bill Viola to Anselm Kiefer, organized by curators who realize that contemporary art often looks best in historical settings, and that the chapel’s graceful (c. 1660) antiquity screams “location, location, location.”

The chapel’s design echoes a Greek cross, with four equal naves united by a central choir area. Currently, Nan Goldin has situated her Sœurs, Saintes, et Sibylles (sisters, saints, and sibyls) within a temporary structure built around this central octagon. Climbing a set of stairs provides access to a platform that overlooks a tableaux of a bedridden woman, her breasts exposed, flanked by a nightstand littered with cigarettes, books and other accoutrements suggesting a prolonged recuperation. Projected on three wall above this inert figure, a 20 minute montage of slides and short video clips proceeds from votive images of Madonnas and female saints to a very personal detailing of Goldin’s difficult family history, with particular emphasis on the suicide of her talented but tormented sister and the artist’s own battle with a host of demons ranging from drugs to depression.

Robleto and Goldin both walk a fine line between sensual and emotional overload, and the specificity of this figurative tableaux suggested a fictional incarnation akin to Robleto’s reshaping of memory through fictional artifacts. However, the voyeuristic nature of the viewing dynamic (theatrically lit in an otherwise darkened chamber, seen from above, at medium distance) deadened Goldin’s tableaux, giving it the shape and feel of a wax museum display. The photo, video, and audio montage, on the other hand, was pointedly confessional, with a first-person narrative driving a storyline that connected Goldin’s progression from family snapshots to her own well-know images of friends and other fellow-travelers that she has, citing Brecht, elsewhere called The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. Unfortunately, the maudlin character of the former overwhelmed the urgency of the latter, and the end result was melodrama.

Joey Fauerso...The Knower, The Known, and the Process of Kowing (installation view)...2004...Oil and acrylic on found backdrop...9 x 16 feet

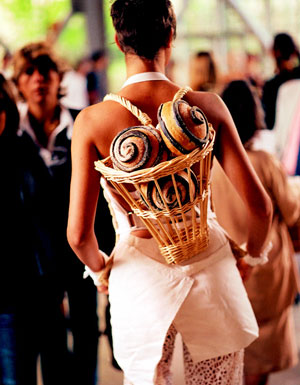

Fondation Cartier, close by via subway in the 14th arrondissement, has become one of Paris’s go-to spots for provocative shows, and Pain Couture by Jean Paul Gaultier was no exception. Gaultier creates innovative high fashion, but entering Jean Nouvelle’s stark glass structure you were overwhelmed by the smell of baking bread. Gaultier set up a functioning bakery in the basement galleries, with smock-clad young women selling fresh-baked delicacies upstairs. Gaultier played off his clothier’s skill by fashioning dress forms out of all manner of baguette, biscuit, and pain poilâne. This part of the show was both a witty one-liner and a critique of the much-lamented decline in the quality of Parisian bread, complete with smell-o-rama. But the real action took place downstairs. After admiring the bakery’s stylized, almost ritualistic actions, a visit to a side gallery revealed bread dough baked into all manner of human forms — heads, feet, torso — that viscerally embodied Georges Bataille’s modernist conflation of sacramental and excremental, utilitarian and sacrilegious. Gaultier’s embrace of the basic element of French cuisine explicitly stated many of the themes implicit in the work of Robleto and Goldin, was a lot of fun to look at, and tasted good to boot.

Four accomplished young San Antonio painters — Joey Fauerso, James Smolleck, Vincent Valdez, and Lloyd Walsh — showed their work at Parsons School of Design show space, another short subway ride away in the 15th arrondissement. Titled A Timeless Montage of Being and Conflict, the works in this show were resolutely representational, figurative, and painterly, in sharp contrast to most of the art going on in Paris these days. For this show Fauerso abandoned her portraits and labyrinthine, multi-figure patterns. The Knower, The Known, and the Process of Knowing locates a host of characters within the rectangular format of a traditional landscape, and is both painterly and theatrical, much like Julian Schnabel’s series of overpainted stage sets. James Smolleck’s paintings adopt the patina of history, and his chosen veneer is the millennial fantasies of Bruegel and Bosch, which he depicts with gusto. To further reinforce the medieval eccentricity of his imagery, Smolleck titles his work in Latin. Lloyd Walsh also successfully revives a historical style for contemporary content, mingling the unblinking realism of Chardin with subject matter — birds calmly smoking cigarettes as they surround a snake coiled in the center of a tree — that is indebted to American characters like Donald Roller Wilson. Vincent Valdez is a draughtsman, not a painter, but like Degas his large pastels and charcoals of paper are as intensely painterly as they are descriptive. The topicality of Valdez’s portrait-based art also ties him to a regional identity — specifically, San Antonio Latino culture. Like the works in his just-concluded McNay Art Museum exhibition, most of the works here are vividly symbolic self-portraits that use descriptive details to enumerate themes and specify character.

French artists must contend with a multitude of daunting forbearers, from Delacroix to Ingres. Haunted by this rich history, budding French bricoleurs now seem more comfortable turning to a video mixing console than to paint and brushes. While the Parsons’ portentous show title and the artist’s own subject matter (with the exception of Valdez) betrayed, perhaps, an overcompensation for the brevity of American artistic history, the quality of their production is a refreshing argument for the continued viability of painting, and this continues to be an object lesson in short supply for contemporary French culture.

Dario Robleto, Diary of a Resurrectionist, galerie praz-delavallade, 28 rue Louise Weiss, Paris 75013. Through November 6.

Jean Paul Gauthier, Pain Couture, Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, 261 Boulevard Raspail, Paris 75014. June 6-October 10.

Images courtesy of the artists.

Christopher French is a writer and artist living in Houston.