Every five days or so, my boys pester me to take them to the grocery store, so they can buy more Sponge Bob toys out of the vending machine there.

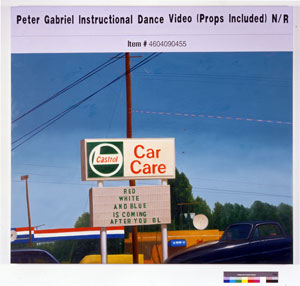

Ludwig Schwarz, Untitled, (Still Life With Chicken Wing), 2003... Oil on canvas. Edition of 4. 52 x 72 inches

For 75 cents, they get a fully formed plastic figure, exquisitely painted, of, say, Sponge Bob dressed in a bunny suit or maybe Patrick or Squidward. As I marvel at their improbable beauty, I also consider how little meaning they must have to the people who paint them (no doubt under sweat shop conditions) in one of those big cities on the coast of China.

Most likely, the visual materials that Ludwig Schwarz sends to China — for transformation into large-scale paintings — present a like group of skilled laborers with a similar opportunity for bemusement. But, for Schwarz, that cultural disconnect is intrinsic to his art, which generally addresses economic conditions that support the practice of visual art.

There are limits to how deeply Schwarz can delve into cultural and economic milieus external to the art world and the affluence that supports it. He’s a well-educated fellow who drives a Volvo and incurs work-related expenses that would make many artists nervous indeed. But Schwarz manages, more so than many of his peers, successfully to critique art market dynamics, by participating in other situations in which money is exchanged for goods.

His current exhibition at Angstrom Gallery is a case in point, as were The Jerk, in early 2003, and RENTTOWN, in 2001.

The Jerk was presented at both Angstrom and at Village Pawn and Jewelry in Dallas. The latter is a place where objects are exchanged for cash and then, with any luck, retrieved when the client presents a larger sum of cash (an ages-old method of charging what amounts to interest, that also plays with the idea of art having some kind of investment value over time).

RENTTOWN, which can be read at least two different ways, saw the gallery turned over the a crew from a local furniture rental store. Paintings, generally of the starving artist variety, were displayed along with the kind of furniture most art patrons never would consider acquiring — but might be willing to rent to own, given suitably ironic, consciousness-raising circumstances.

Sound Chaser is more conventional, at least on the surface. It incorporates a group of 15 large paintings, priced between $5,000 and $7,500, and one small one, at $1,800. It also includes an audio element — based on a drum solo by Alan White of Yes — that Schwarz says most exhibition visitors choose to ignore (which more or less coincides with my own response to it).

Of course, the integrity of Schwarz’s practice is supported by the fact that he works with Angstrom, whose clients recognize that collecting art is but a higher form of buying consumer goods. Many, perhaps most of them, further would admit that their disposable income is generated by a decadent economic system: Yet, again, that awareness enhances appreciation of what Schwarz is doing.

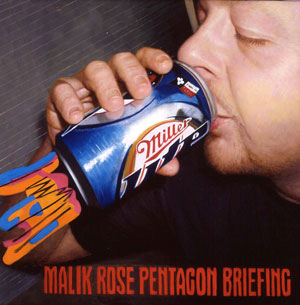

All of the works in Sound Chaser are very capably, often very beautifully, painted by individuals other than Schwarz. Unlike conceptual works from the 1970s, which resulted from an urge toward dematerialization (and ended up being collected, even so, in vestigial form), these powerfully conceptual works need to be realized as objects. In this instance, Schwarz’s images — some straightforward (if radically cropped) snapshots, others composites of disparate pictures and bits of text — are translated into paintings by artists trained in the tradition of Western Old Masters. These artists generally copy portrait images, so Schwarz’s selection of pictures must be particularly mystifying. Still, the customer is always right …

Ludwig Schwarz, Untitled, (Malik Rose Pentagon Briefing), 2003... Oil on canvas. Edition of 4. 18 x 18 inches

None of the works represents an appealing subject. Instead, Schwarz dwells on such motifs as a table littered with dirty dishes, a pudgy woman behind the counter at CashAmerica pawn shop and a vase of withered flowers next to dented mini-blinds. At least two works with parenthetical titles are purely graphic — one features a commentary on Steve Martin’s film The Jerk, the other sports the slogan from Hebrew National frankfurters: "We Answer to a Higher Authority." The tedium of these images, however, is mitigated by the skill and occasional flourishes of innovation with which they are painted. They are not springboards for aesthetic delectation, but for cerebration punctuated by the occasional, visceral gasp.

As such, perhaps because they appeal so strongly to the Puritan in me, I find myself accepting Schwarz’s rather dour vision of contemporary culture. It makes more sense to me than, say, work by Jeff Koons, who professes contentment with the superficial, material world of late capitalism. There are other points of comparison with Koons, of course, including commissioning artisans to execute ideas, but Schwarz is on to something different. Exercising a sort of ironical morality, he seems to understand the limitations of artistic critique but is not discouraged from attempting to push them.

Images courtesy the artist and Angstrom Gallery.

Janet Tyson is a writer and artist living in Fort Worth, TX.