Victor Brauner’s art is typical of a man driven by a personal vision rather than public perception. Brauner was thinking of his subject, the morphed and mutated human figure, and ways to present it, rather than how his presentations would be seen by other people. Characteristically, the show is very uneven; at some points Brauner happens to get his vision across, at other times it remains obscure.

He switches from oil to encaustic to sculpture and back to oil again, searching for new and better ways to present his figures; less concerned with the way the art is made than with his imagery. Some images, like the surprising Loup-Table, 1939, are presented as both paintings and sculpture. He begins with figures in landscapes, like Morte De La Lune, 1932, removes the landscapes as in Memoire Des Reflexes, 1946, then removes the figures to concentrate on intense, owl-eyed faces made from clouds of frenetic chaff as in Tete, 1952.

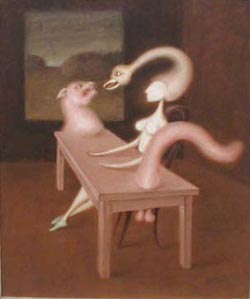

Looking at Brauner’s early paintings is like visiting a peep show. Most of Brauner’s subjects are women, often emphatically so, with highlighted genitalia or breasts. They stand, isolated against relatively inconsequential backgrounds, performing steps in an arcane symbolic fan dance. Fascination, from 1939, sums up the battle of the sexes as seen through Brauner’s psyche: a ghost-woman sits at a male fox-table. Supine but rebellious, the fox’s head snarls at a long-necked bird growing from the woman’s hair. Objectifying one’s sexual kinks is a staple of surrealist art, and Brauner does it with more freshness than usual. For Brauner, sex, as symbolized by his female characters, is an exotic garden full of plants, animals and women, all mixed up together.

Mid-career, Brauner gets less sexy and more spiritual, engraving a mishmash of arcane imagery from around the world onto flat, waxy surfaces like the weathered walls of a Mayan temple. In a classic substitution of knowledge for understanding, the brochure accompanying the show identifies the sources of a few of the images, as if that explained Brauner’s use of them. Unlike the working hieroglyphic vocabularies of the Mayans, Egyptians or ancient Chinese, each element of Brauner’s imagery isn’t vitally significant.

What Brauner wanted out of these symbols is not meaning, but mystery: the divine hocus-pocus that suggests that the world of everyday perception hides a more significant reality.

All images are courtesy the Menil Collection.

Bill Davenport is an artist and writer and was one of the first contributors to Glasstire.