When artists migrate to the United States from whatever country and for whatever reason, inevitably the move precipitates a change in their work. Whether that is due to a change in geographical locale, intellectual climate, or working conditions, it’s an evolution that can be documented over time.

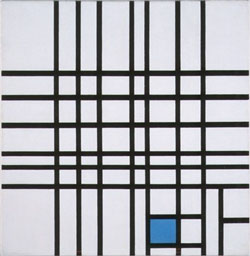

Piet Mondrian, No. 8, 1939-1942 ...oil on canvas, 75.2 x 68.1 cm....Fort Worth, Kimbell Art Museum...(photograph courtesy Kimbell Art Museum)

In the case of Dutch painter Piet Mondrian, that shift is more immediately apparent in his “transatlantic paintings,” a series of 17 works that he began in Europe from 1935-40 — in Paris and then London — which he (re)finished after relocating to New York City in 1940. These were the only paintings that Mondrian worked on while living on both continents, and since he admits that his work was undergoing a radical change in New York, they visibly reflect that activity. As a result, they have a dual quality about them, reflected in Mondrian’s use of two dates when signing them.

Nine of these works form the basis of the DMA’s current, four-part exhibition, Piet Mondrian: The Transatlantic Paintings, Dallas Collects, Color in Space, America Responds. The works in the “transatlantic” portion of the show were organized by the Fogg Art Museum and the Strauss Center for Conservation of the Harvard Art Museum, where the exhibition debuted earlier this year.

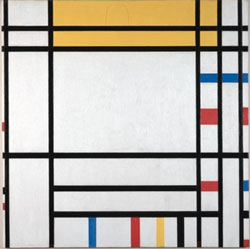

Piet Mondrian, No. 12, 1936-1942 ...oil on canvas, 62 x 60.5 cm....Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada...(photograph courtesy National Gallery of Canada)

The three other sections of the show were organized by Dr. Dorothy Kosinksi, the DMA’s Barbara Thomas Lemmon Curator of European Art: Dallas Collects displays earlier Mondrian works that are in the DMA’s permanent collection; Color in Space realizes an architectural design for a room by Vilmos Huszár and Gerrit Rietveld that was inspired by Mondrian’s painting theories; and America Responds presents works by other artists who were inspired by Mondrian.

If you’re interested in detailed analysis of Mondrian’s “transatlantic paintings,” visit the Harvard University Art Museum’s website. Its scholarship about these works is superb, and it’d be redundant to reprint their findings here. Suffice it to say, the shift reflected in Mondrian’s works is subtle yet illuminating, documenting how his theories of Neoplasticism — his effort to discover a harmony of form, color, and surface — were augmented by his exposure to American culture, especially the vibrant piano jazz he was fond of calling boogie woogie.

What’s more interesting to less art historically-minded viewers is seeing some of these works in person. Mondrian’s eminence in American art can be measured in the sheer number of poster reproductions of his work that litter any number of American walls. But the moothness of such reproductions camouflages the painterly element in Mondrian’s approach, a quality that is made crystal clear when you see them with your own eyes. Modest inconsistencies in hue, faint aberrations in straight lines, the layers and layers of paint that went into crafting the final composition — such signs of painstaking detail telegraph the meticulous work habits of a man who had a very clear idea of his vision, and kept working until he arrived at it.

Piet Mondrian, Place de la Concorde, 1938-1943 ...oil on canvas, 94.4 x 94.3 cm....Dallas Museum of Art, Gift of James H. and Lillian Clark Foundation

In No. 8 and No. 12, you can almost feel Mondrian experiment with a confluence of horizontal and black lines and small quadrants of primary colors, fleshing out the expressive possibilities of his geometrical abstraction. In others, especially Composition with Red, Blue and Yellow and Place de la Concord, the fruits of such experiments become the confident, ascetic yet lively vocabulary that would mark his brief American career, as seen in New York City, New York (1940-42) or the unfinished Victory Boogie Woogie (1942-43).

The “Dallas Collects” portion of the exhibit presents a nice précis of Mondrian’s early career. His younger days in the Netherlands prior to moving to Paris in 1919 were filled with forays into impressionistic landscapes, but after an exposure to pointillism, fauvism and cubism, his acute sensitivity to line, color, and abstraction began to appear. In The Winkel Mill, Pointillist Version (1908) and Windmill (c. 1917), Mondrian plays with warm colors and sparse lines, dropping hints at ideas that would inform De Stijl and neoplaticism in the late teens and 1920s.

Less satisfying are the other two parts of the exhibition. “Color in Space” is a room recreated from designs that Huszár and Rietveld published in 1924 but never built. The design attempts to transpose Mondrian’s two-dimensional painting theories into three dimensions, but it only accentuates their inherent flatness. Walking into the room and sitting in the included chair only makes you feel like you were dropped into a grid stretched over a cube; with large, rectangular, red, yellow and blue areas adorning walls interrupted by clean black lines and ample space. It’s an interesting idea to see, but it was probably an exercise that looks better on paper than in actuality.

“America Responds” is by far the most curious section of the show. While the immediate impact of Mondrian’s ideas on American artists is undoubted, including these works — by artists such as Leon Polk Smart, Fritz Glarner, Charles Biederman, Burgoyne Diller and Ilya Bolotowsky — is a tad daft. Admittedly, the debt to Mondrian is readily apparent – especially in Smart’s Homage to Victory Boogie Woogie #1 and Homage to Victory Boogie Woogie #2, two explorations of Mondrian’s jazzy influence that Smart makes entirely his own. But the inclusion of these works doesn’t enrich or heighten an appreciation of Mondrian; they only make literal the obvious. Plus, the fact that some of these artists were expatriates themselves undercuts the “American” theme. Fortunately, the last two sections of the show don’t distract too much from the first two sections, which highlight Mondrian’s works — the main draw here, and eminently compelling by themselves.

Bret McCabe lives in Dallas, Texas.

1 comment

Are there forums or other sites where opinions are shared about paintings by Mondrian?

Who dares to describe in detail what he/she likes in a painting.

I am especially interested in “Place de la Concorde” and “Victory Boogie Woogie”.

– a dutch Mondriaan fan –