There’s a particular joy and frisson when an exhibition seems to have a cosmic serendipity of timing, when the works feel like a balm or antidote to the times. The summer Artists-in-Residence exhibition at Artpace in San Antonio marks the first time that all three of the resident artists (one local, one national, and one international) are women of color, and the works are melancholic and incisive, charged with a wisdom of the world and its cruel machinations, and a grace in recognizing an elemental beauty behind it.

Curated by Jeffreen Hayes, who runs a similar residency and exhibition space in Chicago — Threewalls, the three artists here — Zoë Charlton from Tallahassee, Botswanan-born Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum, who resides in Johannesburg and Toronto, and San Antonio resident Jenelle Esparza all create immersive installations tinged with sadness and pain, but also a mysterious wonder.

On the roof, Charlton recreates her grandmother’s home in Tallahasee and flips it on its head. Charlton’s grandmother sold her home to developers who razed it and turned the land into a subdivision of ubiquitous Floridian McMansions. The house is colored pale turquoise and hollowed out, resembling an above-ground pool, and inside the house are miniatures of similar modest homes — of a rapidly receding time of working-class and minority home ownership and stability. The house appears as if it has been blown away to a dark Oz, the smaller houses inside are trapped, the walls collapsing on them like a malevolent sacred geometry. Gentrification, and by extension late capitalism, have become Shiva, destroyer of worlds (to quote the inventor of the atomic bomb Robert Oppenheimer), blotting out the sun, erasing the past, and leaving a cavernous, translucent shell. There is a reason why I reference the Tarkovksky film Stalker and the concept of the Zone so frequently lately, because the world is constantly off — filled with the simulacrum of a house, a community, a job, a life. Charlton’s rooftop installation conveys this with a ruthless desolation under the glaring sun.

In a stark and lovely contrast to rooftop installation, Charlton’s murals on the second floor depict large bodies of woman of color bursting with clouds and birds. The pieces feel cathartic and exultant, expansive and bristling with defiance and hope. The wonder of human existence cannot be erased by the churning leviathan of capitalism, class, and racism. One bird is painted in mid-flight, straining at the edge of a window to escape and disappear into the blue sky.

Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum was born in Botswana and has lived all over the world. Her installation centers on an elegant “salon”, lush with garden plants and velvet furniture. Sunstrum’s watercolor works in and around the installation are pastoral and dislocating, tinged with a dystopian, science-fiction element. There is an elegance and velocity to Sunstrum’s works that feels distinctly narrative, recalling the worlds created by the great French artist Moebius and Alejandro Jodorowsky’s graphic novels such as The Incal. The paintings of smoking volcanos, stark cliffs, and veiled and collared guards, faceless figures in angles of leisurely repose, work on two levels, swinging like a hinge between worlds. They articulate a reality of colonialism — that it was a dark future for the world it imposed itself on, some distant empire sweeping through the lands. Conversely, the works can be viewed as the counterfactual what if…, the dream of a sort of Afro-indigenous futurism.

The title of Sunstrum’s installation Earth and Everything suggests the experience of expansion, that bolt when one’s surroundings seem to flutter like curtains in the breeze revealing what lies behind — which is everything.

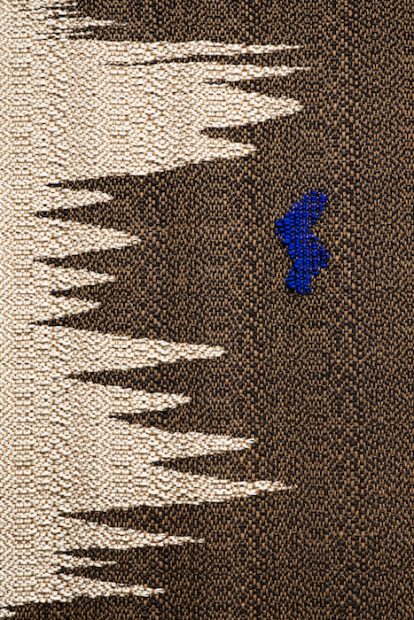

Gathering Bones, the installation by Jenelle Esparza, is the most immediately arresting and moving of the three. Exploring the aesthetic blooms and tails of cotton and its legacy of oppression and misery on the bodies of those who toiled (often enslaved) to harvest it, Esparza’s work is heavy and anguished, but also carries a majestic, ethereal resonance, like standing in a medieval cathedral now, and reckoning with the pain needed to erect such an edifice to God.

Each of Esparza’s pieces is tied to the history of cotton labor and the toll it took on the human body. Three gorgeous tapestries woven from cotton unspool out onto the floor like arteries or entrails. The patterns of the tapestries have an inscrutable, exotic pattern suggesting the global reach of the cotton industry. Two gorgeous, curved pieces of driftwood hang, lacquered and stained with an almost crimson sheen. The resemblance to sinew and muscle is unmistakable, the arch of the back stooped in the fields or curved body about to strike another person. There’s group of cotton flowers, bronzed and encased in glass, demonstrating their preciousness and the thorniness of the harvest, literally and metaphysically. Bone white cotton is braided into a thick rope resembling the cables of a sailboat or the handle of a whip. A hoe of glass is delicately unsettling, like a dentist’s tool or an article for torture.

All of Esparza’s works are aesthetically pleasing and symbolically disturbing. This is a current through all three of the artists’ works in the exhibition. Beauty is used not as a veil, but a lens to cast the world into sharp relief. Look at this horrible, beautiful place. Really look.

Through Sept. 9 at Artpace, San Antonio. Photography: Charlie Kitchen