When I was around 19 or 20, my sister, Joey Fauerso, had a gallery with Michael Velliquette called The Bower, and I would come down for the openings and the nights would often end up at a party at Chuck Ramirez’s house. At the time, I wasn’t really familiar with Ramirez’s funny and elegantly gorgeous photo work, but to my college sophomore self who was just beginning to write poetry and get really into harsh noise, Ramirez seemed like the romantic ideal of an “artist.” Archly buzzed, brim of hat cocked askew, smoking in a way that was casually cinematic, and mordantly funny — Ramirez exuded a louche bohemian cool in his vibe and lifestyle that was and still is an inspiration of what a countercultural life in a Class B cheap city could be.

In Angela and Mark Walley’s (of Walley Films) affectionate and moving documentary Tía Chuck: A Portrait of Chuck Ramirez, Ramirez is convincingly depicted as a preternaturally gifted artist and local star whose tragically short life does not diminish a creative legacy and personality that increasingly, and rightfully, is beginning to feel legendary. (The documentary premieres in San Antonio this weekend.)

A doted-on and social child, Ramirez may have not had the Heavy Metal/Yes Album Covers-like sketchbook skills of his Dazed and Confused high-school bong bros, but he was gifted with a brilliant, generous eye that saw the fluttering curves of beauty in trash, empty packaging, raw meat, and the leftover mess of a boozy Sunday dinner. Unsurprisingly for a person who lived in a flashy, performative fashion, Ramirez’s life was well documented in video, audio and interviews. The Walleys, over a five-year process, deftly incorporate such material with subtle recreations and interviews with family, friends, and peers to craft a seamless narrative of an artist’s ascent.

Basically self-taught, Ramirez emerged as a strikingly vibrant and lush conceptual artist, along with a generation of San Antonio artists, who established a freewheeling scene in South San Antonio. Ramirez, though of Latino descent, was different from the artists in the Chicano movement. His works were less political, more baroque and sensual, and yes, Ramirez was lighter skinned. At one point, a certain community schism came to a head in a contentious UTSA show decried by local Chicano artists as showing only “coconuts” (brown on the outside, white on the inside). Ramirez, in the witty and carefree manner in which he lived, turned this brusque jibe on its head with a series of minimally beautiful photos of coconuts suspended in a white plain — a meditation on the absurdity and grace of being.

Akin to other working-class, distinctly “local” artists of other cities (like Charles Bukowski, as in embodying the myth of their hometown city that they themselves weave), Ramirez had a fairly prosaic day job as a graphic designer at H.E.B. headquarters. This gave him access and insight to the mysterious and often elegiac beauty in everyday products and packaging. “Chuck loved beauty and saw it everywhere,” is a sentiment echoed by several of his friends in the film, one that could easily be pat — a drug-store card sentiment — but in this case is apt and germane. Even though his art wasn’t explicitly political, his lifelong project of reclaiming the low and casting it as extravagant feels righteous. Ramirez lived and worked modestly in a “provincial” South Texas city, but lived like eccentric European nobility. Everyone could do this, splendor was all around.

Ramirez was eventually able to quit his job and earn a living from selling his art. This wave crests in an ecstatic sequence in the film where a work by Ramirez is auctioned at Christie’s in New York. In a perfect miniature of pre-2008 gilded-age flushness, the bidding begins at seven thousand and immediately a collector bellows “20 thousand!” and Ramirez, watching from the back of the room, beams like George Clooney.

The film, just like Ramirez’s works, is tinged with a sadness, rumble of death in the distance like an early-morning garbage truck. Ramirez lived hard and free, with the heaviness of an HIV-positive diagnosis giving things an urgency — to see the sun go down, to luxuriate at the table late into the night. His death was bleak and banal (he fell off his bike and hit the back of his head) as is often the case with incandescent ones. Sandy Denny fell down the stairs, Jeremy Blake walked into the sea. Sometimes those that burn bright get snuffed out.

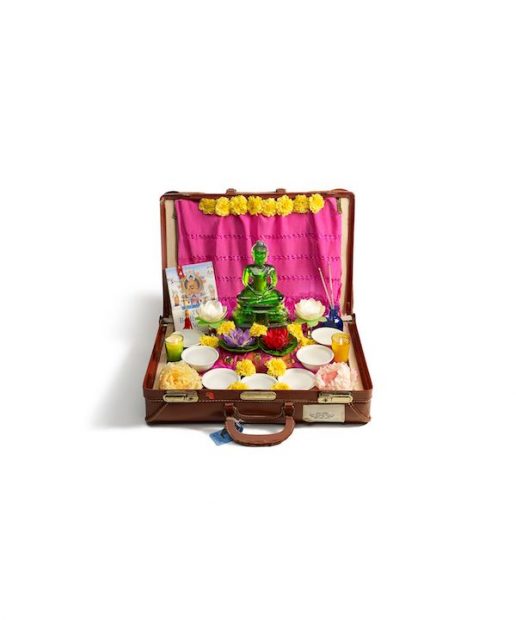

The final scenes of the succinct documentary are open-ended and suggest a second phase of Ramirez’s life as his work is shown more extensively throughout the world. Ramirez loved Dia De Los Muertos and making altars for departed family and friends of the things they loved in life, things that brought them joy and delight. Ramirez’s work, and now this film, are sort of Dia De Los Muertos altar to Ramirez, which is by extension, a kind of altar for those of us who love Ramirez’s work. There’s a profound and ongoing generosity in Ramirez — in his art, and in this film about him. That is, after all, why he became known as Tía Chuck.

‘Tía Chuck: A Portrait of Chuck Ramirez’ premieres this weekend on Cinco de Mayo, the 5th of May, in the Tobin Center’s H-E-B Performance Hall in San Antonio. Tickets are $20, with some of the proceeds benefitting Sala Diaz and Casa Chuck, an invitational residency program run out of Ramirez’s former home. For more info, please go here. If you’re in Houston, the film will screen at the Aurora Picture Show as a part of the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston’s exhibition Right Here, Right Now: San Antonio, on June 14 at 7:30PM.

Images of artworks courtesy of Ruiz-Healy Art.