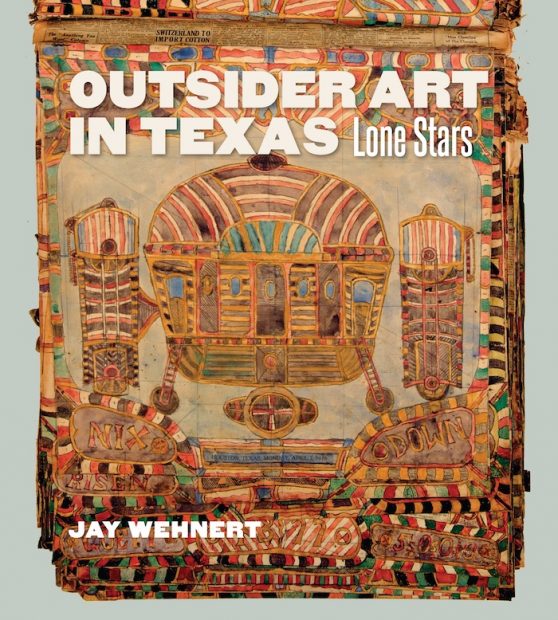

Ed note: The following is a chapter from Jay Wehnert’s new book, ‘Outsider Art in Texas: Lone Stars,’ published by Texas A&M University Press, which ‘takes readers on a visually stunning excursion through the lives and work of eleven outsider artists from Texas, a state particularly rich in outsider artists of national and international renown.’ Buy the book here, and, this Sunday, May 6 from 4-7 pm there is an opening reception at the Webb Gallery, Waxahachie, for a new show titled ‘LONE STARS: A celebration of Texas Culture in Art,’ which will feature the artwork of the artists featured in this book, including that of Consuelo “Chelo” González Amézcua.

This chapter is is reproduced with permission from Texas A&M University Press.

****

Living on borders and in margins, keeping intact one’s shifting and multiple identity and integrity, is like trying to swim in a new element, an “alien” element. —Gloria E. Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza

“Outsider” or “insider,” “self-taught” or “trained,” “folk art” or “fine art”—when applied to art and artists, these labels can be like borders that serve as divisions between regions of genuine meaning and understanding. Words, like borders, suggest either-or distinctions when real meaning may actually be found in the gray areas between these categorical bisections.

The border region between the United States and Mexico presents just such a phenomenon from both geographical and cultural perspectives. Borders have long divided geography and people that have historically had more fluid and porous relationships. Established for political and nationalistic reasons, borders often do not consider the people and cultures that coexist along them. The region along the border, consisting of territory on each side, comes to take on its own identity, often a hybridization of each. James Griffith in Southern Arizona Folk Arts describes the borderland as follows: “Belonging truly to neither nation, it serves as a kind of cultural buffer zone for both, cultivating its own culture and traditions. Like other borders, it both attracts and repels, like them it is both barrier and filter. It is above all a stimulating cultural environment.” When that border artificially separates countries that have intertwined histories but have grown apart culturally and economically, the culture of the borderland becomes even more complex. Norma E. Cantu writes further,

The pain and joy of the borderland—perhaps no greater or lesser than the emotions stirred by living anywhere contradictions abound, cultures clash and meld, and life is lived on an edge—come from a wound that will not heal and yet is forever healing. These lands have always been here, the river of people has flowed for centuries. It is only the designation of “border” that is relatively new, and along with the term comes the life one lives in this “in-between world” that makes us the “other,” the marginalized.

Artist James Magee, who has spent most of his adult life living and creating in the adjacent border cities of El Paso, Texas, and Juarez, Mexico, describes the borderland succinctly, saying, “It is truly neither here nor there.”

The surprising examples of this cross-cultural exchange in the borderland are varied and full of depth. They include the Tecolotes de los Dos Laredos (Owls of the Two Laredos), a Mexican minor league baseball team that was shared by the sister cities of Laredo and Nuevo Laredo and was the only team in the league to play games in both Mexico and the United States, thus bringing a more nuanced interpretation to the term “our national pastime.” Perhaps more well known, legendary deejay “Wolfman Jack” broadcast on KERF-AM from the Texas border town of Del Rio, on its 500,000-watt “border buster” signal that originated from radio towers in its sister city across the border, Acuña, reaching young Anglo late-night rock and roll ears as far north as Canada in the 1960s.

The borderland and the city of Del Rio was also the home of Consuelo “Chelo” González Amézcua, a remarkable artist whose life and art embodies much of the richness and complexities of this liminal region. Born in Piedras Negras in the Mexican state of Coahuila in 1903, the young Consuelo, who was known to all as “Chelo,” emigrated across the border with her family to Del Rio in 1913. The family was escaping the violence and upheaval of the Mexican Revolution, arriving in Del Rio on Thanksgiving Day, the most American of holidays. Her father eventually found work as an accountant, and as the family prospered in their newly adopted country, they moved from the predominantly Hispanic part of town to a more traditionally English-speaking neighborhood. Thus, the experience of living in two bordering worlds had now already been part of young Chelo’s early life at both national and local levels. She was moving between and among societies and cultures in ways that would later emerge in her art.

Chelo attended school in Del Rio but did not graduate from high school. Her interests and pursuits appear to have been more artistic than academic. She was a very social young woman, always singing, telling stories, and entertaining her friends. Her many years of working at the Kress five-and-dime store on Main Street in Del Rio, where she was affectionately known as “the candy lady” or “la dulcera,” may have seemed like the quintessential all-American life for a first-generation Mexican immigrant young woman. Chelo maintained a keen interest in the arts and harbored hopes of studying at the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City, which counted world-renowned artists such as José Clemente Orozco and Diego Rivera as former students. She was accepted to attend, but the death of her father in 1932 prevented her from leaving home. This cemented her deep cultural familial ties to her mother, with whom she continued to live until her mother’s death a decade later. Chelo would never marry. She and her sister Zaré, who also remained single, lived their entire lives together in the family home. This appears to be another form of cultural blending that Chelo developed in her life on the borderland. Her Mexican heritage may have obligated Chelo to her parents and the needs of the family, but in the aftermath of their deaths she was able to establish a life as a more independent working woman and then later as an artist.

Chelo Amézcua developed an energetic and creative lifestyle in Del Rio. In addition to her work at Kress’s candy counter, she performed for organizations such as the Knights of Columbus at local and regional gatherings. Chelo wrote poetry and songs, often performing her original works in small and informal public settings. She also pursued drawing and developed as a visual artist. It was at just such a civic gathering in 1964 that Chelo came to the attention of Amy Freeman Lee, an artist, activist, and cultural arts patron from San Antonio. Lee was in Del Rio for a dinner in her honor, and part of the evening’s entertainment included Chelo’s singing. Lee would recount, “In the evening, I went to a dinner in my honor . . . and, as I rounded the buffet table, my eye fell on a drawing on the dining room wall. The visual impact attracted me like a magnet, and as I approached the drawing, I found it even more extraordinary than I’d first thought. It looked as though some ancient Persian had spun the design out of spider webs and thistles.”

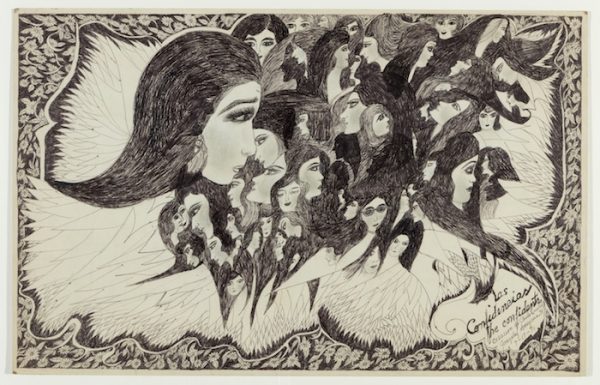

Consuelo “Chelo” González Amézcua, Las Confidencias, 1971. Pen and ink on illustration board, 14”x 22”. Courtesy of Webb Gallery, Waxahachie. Photograph by Kevin Todora.

Amy Freeman Lee’s enthusiasm for Chelo and her work culminated in her organizing a solo show in 1968 at the Marion Koogler McNay Art Institute in San Antonio. In her insightful essay that accompanied the catalogue for the exhibition, Lee provided Chelo’s own description of the deep connections of her life and art. Chelo recounted,

My parents were poor, but they always tried to create happiness for us. They played the guitar and sang with joy. This family of mine took care of me as if I were something special to them. I did not play with other children, my family was enough. I used to sit under the trees by the San Felipe River where I went to swim and watch nature, especially birds. My father and mother told me stories, and my dear sister Zaré, who took special care of me, sang to me and was the inspiration of many of my musical compositions. I was always a dreamer, and I am still painting my dream visions.

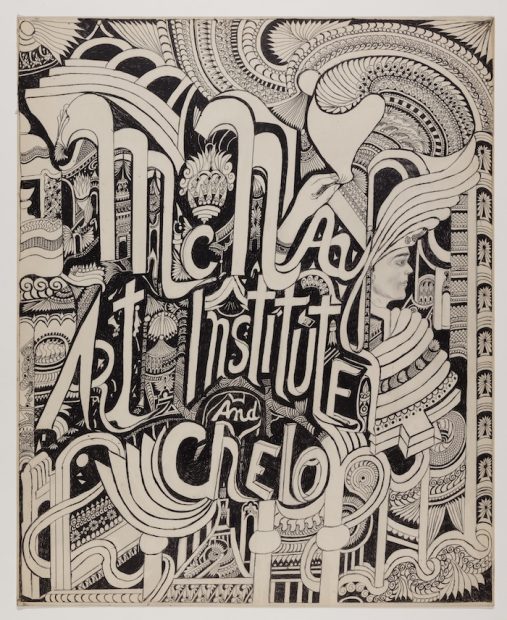

Consuelo “Chelo” González Amézcua, McNay Art Institute and Chelo, 1968. Pen and ink on illustration board, 28”x 22”. Courtesy of Webb Gallery, Waxahachie. Photograph by Kevin Todora

In this brief story of her childhood, Chelo touched upon several of the core aspects of her life and art, including nature, her deep family ties, her special place in the world, and the visionary realm of her art. In one of Chelo’s hand-drawn posters for her own exhibition she captures many of the cross-cultural and historical references that inhabit her art.

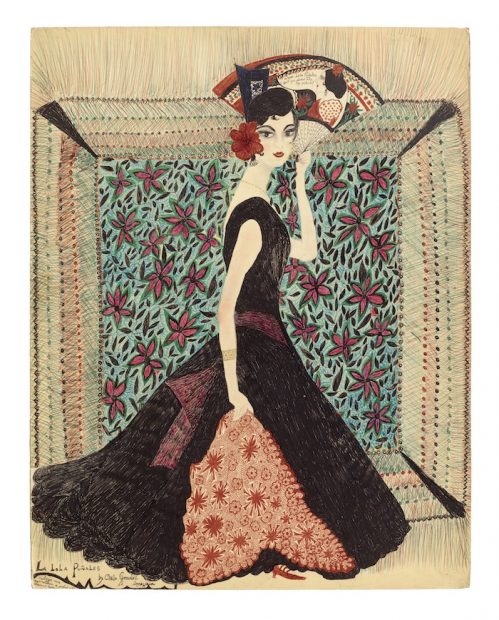

Consuelo “Chelo” González Amézcua, La Lola Puñales, 1966. Pencil and ink on paper, 28” x 22”. Private collection, Houston. Photograph by Thomas DuBrock.

While Chelo Amézcua’s art embraced her bicultural experience of the Texas-Mexican border, she also directly expressed the outsider’s perspective in her lack of formal awareness of established culture and its conventions. In his book Mexican American Artists, art historian and scholar Jacinto Quirarte interviewed Chelo and asked if she was familiar with a particular artist that shared her finely detailed pen and ink technique. Echoing Jean Dubuffet and his creators of art brut, she replied, “No, I am not familiar with anything. I am not familiar with cultural things.” Chelo was, instead, intimately familiar with the aspects of creation, not of man’s cultural making. She experienced her creativity and talents as God-given gifts that were manifestations of the divine. Her art was a spiritual act as much as a creative one. Her drawing practice involved contemplative prayer, devotional acts, and tribute to its true creator. Her subjects also reflected her interests in the sensually corporeal world. In her drawing La Lola Puñales, she depicts the infamous flamenco dancer who died under mysterious circumstances. Chelo’s notation of the drawing in the lower corner describes its composition and style: “dibujo sin symetría a pulso con pluma y lápiz” (“drawing without symmetry freehand with pen and pencil”).

Chelo Amézcua’s drawings were created in a geographic and cultural borderland. The phenomenon of existing and creating within a space that is “in between” permeates her art. Her love of Bible stories and ancient history provided much of the specific inspiration for her drawings. However, Chelo saw her art as also being innovative and forward looking. She called her finely drawn creations “Texas Filigree Art” as well as “A New Texas Culture.” “Filigree” referenced the finely designed ornamental metal work of her indigenous Mexican culture, while simultaneously placing her art firmly in her new Texas homeland. Thus, she was achieving the borderland’s creation of something unique unto itself.

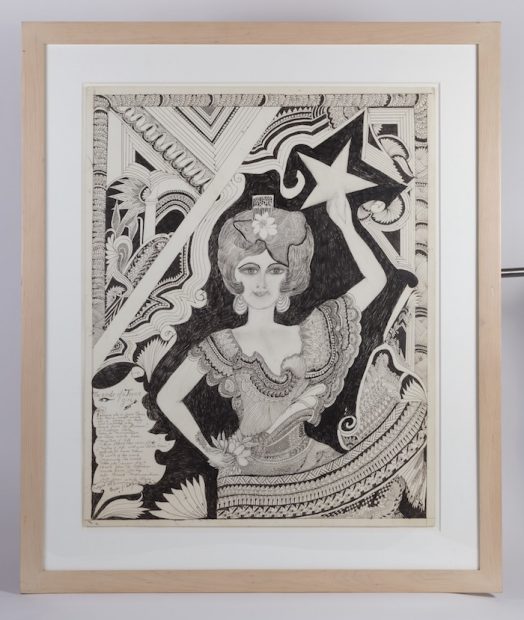

This biculturalism is wonderfully illustrated in her drawing The Smile of a Texan Girl. Rendered in her singular medium of ballpoint pen, the drawing embodies the dualities of her life and creative experience. The drawing’s subject, dressed in traditional Mexican style, is rendered in Chelo’s signature filigree, which further accentuates her native Mexican character. Close consideration reveals that the artist has embedded references to the state of Texas in her subject’s hairstyle and in the neckline of her dress. She holds aloft a lone star, the iconic symbol of Texas. Chelo’s bicultural perspective is further enhanced by the drawing’s title. The woman in the drawing, who may represent Chelo herself, embraces her adopted homeland. She is called a “Texan girl,” and her smile conveys her pleasure and pride in this. Chelo often incorporated poetry into her works, providing another layer of depth and texture to her compositions. She wrote these lines on the drawing:

Because she is from Texas

she has a sweet smile

she is always so happy

and I wonder why

smile from the Indians

or Hernan Cortez

may be Maximilian

or Dear uncle Sam

Mystery of life

Whose blood her veins flow?

Mystery of life, will you let me know?

and she’ll never know

the worth of her smile

Conquering the world

When she passes by

smile from the Indians

smile from Cortez

she kissed Maximilian

but loves uncle Sam

Consuelo “Chelo” González Amézcua, The Smile of a Texan Girl, n.d. Pen and ink on paper, 29 x 23”. Courtesy of Paige and Todd Johnson. Photograph by Jack Thompson.

Chelo Amézcua’s imagery and words strongly convey the deep sense of historical and cultural dualities present in her life and art. She experienced the world in Del Rio from both sides of the border and strived to create her own world somewhere between.