Austin-based neon artist and musician Ben Livingston got a bit choked up during a gallery talk for his Spirit Houses exhibition at the San Angelo Museum of Fine Arts a few weeks back. He was recalling the emotional experience of retrieving some of the wood that he used as cradles or homes for his colorful tubes of light. The artist happened to drive past a row of historic structures that had been built as residences for former slaves as the small wooden homes were being demolished in East Austin.

“These houses were like jewel boxes, collapsing into dust,” he said. “I had to do something to salvage the spirits ingrained in the lumber and lingering there in space.” Other potent timber receptacles for the fifteen vibrant rainbow staffs in the San Angelo show were obtained from a century-old barn in a Tom Green County cotton field.

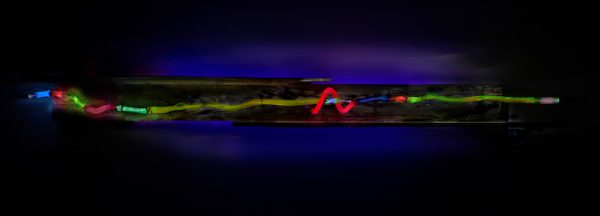

Livingston’s neon tubes repose in their vessels of aged flesh-and-bone from ancient trees like shaman’s wands, banded with opalescent purple, pink, blue, green, orange, yellow and red. Argon gas pressure in the tubes reacts with the frequencies generated by tiny solid-state transformers to make bubbles flow like corpuscles. Viewed closely, the neon glow illumines the abstract wisdom inherent in the wood.

The artist’s inspiration for these alternately meditative and mesmerizing pieces came during a trip to Nepal. It evolved during extended, months-long treks through Thailand, Laos, Burma, and Cambodia. “I kept noticing these little shrines in yards and businesses,” he explained. “They looked like smaller versions of Thailand’s wat temples. People place little dolls of humans and elephants and other animals in them and make offerings of incense, fruit, bottles of red Fanta soda with straws, pieces of cooked chicken, sugar and tea. They’re homages to the ancestors and they express the Asian animist concept of nature.”

Livingston further traced his inclination to be a maker of spirit homes to his childhood in Victoria on the Texas coastal plain. “I liked to make doll houses as a kid,” he chuckled. “I made one for every girl I knew. Then I wanted to be an architectural model builder. I didn’t want to be an architect, I just wanted to make the models.”

Having written several magazine articles about Victoria, I can attest that the town may savor more artistic activity per capita than any other burg in the state. Ditto in the category of big buckets of strange. Consider the late Henry J. Hauschild’s Nose Gallery, for instance, which once occupied his home next door to the 1893 Hauschild Opera House. Hauschild’s business card identified him as a “Physiognomist,” “Bibliopolist,” and “Cognoscente di Eccellentissimo.” He curated a “famous, unique, extraordinary ‘Nose Gallery’” of paintings, photographs, and sculptures of large, unusual, or prominent nasal promontories. Hauschild told me that his extensive study of human nature led to the conclusion that “a long nose and a good head are inseparable.”

Livingston believes that his artistically inclined mother Polly Lou had her own proboscis immortalized in Hauschild’s gallery. “She was a huge proponent of the arts throughout my childhood,” Livingston says. “She brought in fine artists from all over to show their work at our house for the events she organized called Polly Lou’s Art and Tea Parties. She later designed crazy-elaborate parties all over Texas. I started building sets for my theatrical grandmother in San Antonio, and then I designed sets for Polly Lou’s parties. In 1980, Washington Project for the Arts commissioned us to turn their entire space into a Texas dance hall. And boy did we.” The memorable event included a sawdust floor, a Terlingua chili champ, a Gilley’s mechanical bull, and just about every Lubbock musician who ever yodeled at a flatland moon.

The installation also introduced Livingston to neon, in the form of a 1950s Dutch Masters Cigar sign that hung behind the bar. “I’ll never forget how I was smitten by the linear quality of that neon,” he says. “That’s when I realized the possibility of drawing with light. Like an electric crayon.”

In 1993 Ben grabbed an NEA fellowship to further his experiments with the cool colored tubes. He developed his own unique style by pulverizing rocks that contain phosphorescent minerals. This enabled him to produce the rich opaline hues. For years he operated a successful business, Beneon, restoring neon signs for Austin landmarks like the Continental Club on South Congress and Grove Drugs on Sixth Street. He also designed sets with neon for Austin City Limits. But at some point, he reached a kind of commercial overload and shut the business down to concentrate on neon art. Today, Mick Jagger owns a Livingston piece.

Adjoining the large San Angelo Museum of Fine Arts gallery that contains Spirit Houses, a smaller space exhibits intriguing images and artifacts from the region’s past on loan from Fort Concho National Historic Landmark. “It is not a history exhibit,” notes SAMFA director Howard Taylor. “It’s intended to provoke thoughts and memories of people and events which in many cases are long forgotten — and to sense the presence of those thoughts and memories in the Spirit Houses sculptures. They remind us that our minds are full of ghosts all the time.”

I was especially taken by the two images of Booger Red Privett, one of my favorite personalities from rodeo and Wild West Show history, and by the windmill advertising image of Corinne Baker Wingfield. In her costume Wingfield reminded me of a pioneer West Texas version of Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. Together, the Spirit Houses and the Concho Valley exhibits are entitled I Was Once Here: Ghosts and Memories.

Though Livingston’s San Angelo neon works address the immense mystery of the relationship between this world and the spirit world, there remains a playful element to his ‘drawings with an electric crayon.’ And that side of his art output is even more prevalent in his music. There, the sense of ironic glee reminds me a bit of the playfulness and homemade ritual of the grand New Mexico performance poet Larry Goodell.

You can find some of Ben Livingston’s music on YouTube and other online spots, but the stripped-down versions there are often not nearly as pedal-to-the-metal fullblown as his bigger-production-value CDs (for excerpts see beneon.com). While most of his tunes are sung in understandable English, I also like the songs with made-up languages and the scat tribute to Tuvan throat singing. One composition, Golfers Are Fat, would make an ideal soundtrack for current newscasts. Another, Smart Fools from Art Schools, merits special attention here.

The composer partly includes himself in the ribbing, jiving that “art school folks suffer life’s cruel jokes that keep us from finding ourselves.” We’re “sucked in by the mystique and hammered by critique” and we think we’re “wanted dead or alive.” Launching into some name-check verses, Livingston croons: “Jean-Paul Sartre was at the Department of Art, but he just couldn’t find his way out the door. So he confided in Beuys, who made a terrible noise as he threw a handful of lard on the floor.” Then we hear about Marcel Duchamp and his nudist camp where “he just loved playing chess with all them gals.” Michael Tracy makes an appearance, accused of stealing blood and stuff, and then cartoon shoot-em-up sound effects are deployed when the narrator thinks he spots Leo Buscaglia but it turns out to be Julian Schnabel and we’re told to “run for your lives!”

The song’s closing verse leads with the cranky, tongue-in-cheek admonition that “smart fools from art schools” should “quit actin’ like a bunch of little ol’ squirrels,” then scores extra bonus rhyming points with the acknowledgment that “my voice ain’t as good as Merle’s,” and brings it home on the peppy note that “you don’t have to be a drum majorette to twirl.” Livingston caps it: “Go on now, have yourself a good time!” I don’t know about the squirrel deal, but yeah, reckon I can kinda relate.

‘I Was Once Here: Ghosts and Memories’ with Ben Livingston’s ‘Spirit Houses’ is on view at the San Angelo Museum of Fine Arts through February 4.

2 comments

Excellent writing and narrative on Ben. You have captured him perfectly. Great work and an even greater soul.

Thank you, Jay.