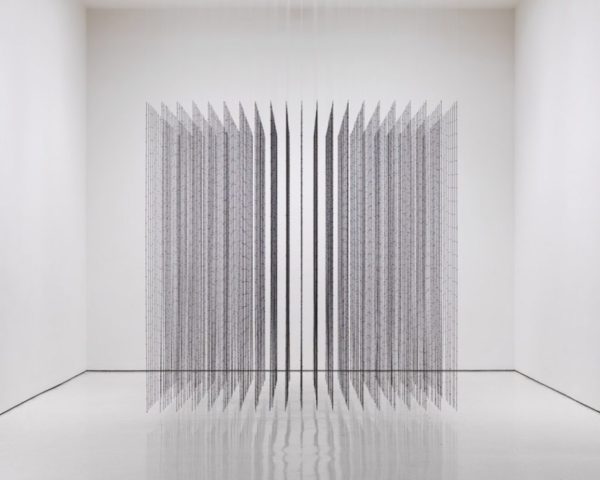

The stillness of an abortion, the vacuity of a stillbirth: Mona Hatoum’s Silence stands resolutely in dissolution, as if its translucent test-tube structure were a bottomless, palimpsest ghost of what could have been. It’s no wonder that curator Michelle White — in Hatoum’s survey up now at the Menil Collection in Houston — installed Silence directly opposite Impenetrable, a gridded rain of barbed wire.

Hatoum’s work, spanning decades, is vast. A Palestinian woman raised in Beirut, her works tackle far-reaching concerns, from war and violence to politics to the entrapment of domesticity. But what I think is so prevalent in most of this work — and so pressing not only decades ago but with each new tumultuous day — is the works’ corporeal relationship to womanhood.

Silence — like a slap — reminds us what it is for a woman to bury and hold stress and shame deep within her body. Its echo renders Impenetrable as not only some kind of fortress, but also a battle cry. As we traverse the grid, the barbs read as swarming flies, migrating birds, the photographic negative of stars in the galaxy. Our eyes fall into a void, and we picture our bodies falling within it, the barbs digging and ripping into our flesh.

A perverse desire to imagine self-inflicted damage is the crux of much of Hatoum’s work, and she effectively elicits this desire by scaling up overlooked domestic objects or — almost like an errant punctuation mark — employing disconcerting materials in an otherwise hypnotic piece.

La Grande Broyeuse (Mouli-Julienne x 17), 1999. Mild steel, main sculpture 135 x 226 1/2 x 103 1/2 inches. Each disc 2 x 67 x 67 inches.

La grande broyeuse (Mouli-Julienne x 17) is one such example. Here Hatoum has blown up a rotary food mill to 17 times its original size. Its spindly tripod legs and upturned tail make it loom like a giant scorpion or a mutated grand piano. But as we peek into the vegetable chamber, we imagine ourselves crawling into it like a womb, or a tomb, resigning ourselves into the fetal position, the handle methodically pressing onto and crushing our bodies.

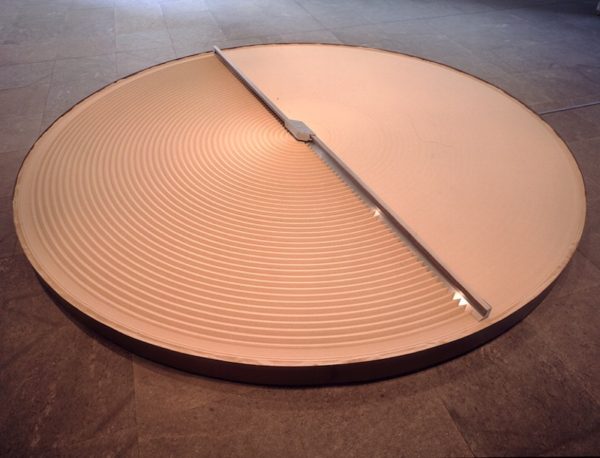

The piece + and – spins as a continuously redrawn zen garden. But as we’re quietly seduced by the raking and flattening and raking and flattening again of sand, we become aware of the eerily violent apparatus making it happen. It’s a sickening kind of mechanization, yanking us out of our hypnotized state and reminding us of those infinite circular irrigation fields we look down on while flying over farmland. The metal teeth demarcating those perfect lines in the sand evoke the industrial accident. What if our hand got trapped in it? Would it mangle, would it sever?

Hatoum’s work can be violent and quiet and tepid and gross. It makes us confront desires within ourselves we’d rather not. But within the context of an oppressed body (and the context of identity politics roiling within the art world), a fair question to ask is: is her work doing something besides being eerie? The answer is yes. It manifests a profound and uncomfortable thing we already know, which is that we’re stuck within a system that uses our bodies as parts to be touched, exploited, manipulated, and dismissed.

Is this work’s psychological weight self-indulgent? You could try asking this of the countless women (and some men) in recent weeks who have excavated and laid bare deeply personal and painful memories, dismantling powerful sexual abusers, one after the other. What makes Hatoum’s work feel so urgent, this very second, is its unlikely optimism and vision for mobilization, and its invocation of new power dynamic.

That’s because — and to be clear, I’m not referring to actual self-harm but rather to the ideation of one’s own physical suffering — the acceptance of pain (strangely and counter-intuitively) entails a kind of reclamation of power within the context of an oppressed body. In order for the abused to speak truth to power, they must revisit the pain a predator thrust upon them, sit with that pain and even galvanize it in order to weaponize it against the predator. This model of power opposes the traditional patriarchal myth of the singular, ambitious male climbing his way up the ladder (under the selectively generous eye of the patriarchy itself). Hatoum’s work seeks the cumulative voice and a non-hierarchical structure. It’s amoebic, and, as we’ve already seen with the fall of Harvey Weinstein and company, it’s potent.

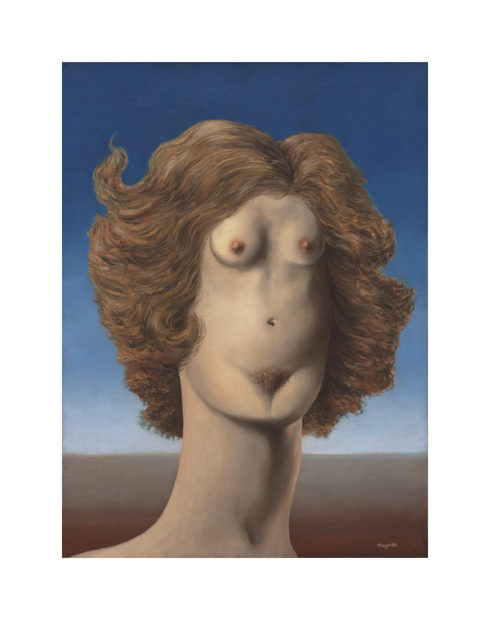

But Terra Infirma also confronts a longer history by intermingling with the Surrealist gallery in a curatorial decision by White that is smart, angry, and brave. We see this most poignantly with Hatoum’s Jardin public, from 1993. Jardin public, a wrought-iron chair with a fuzzy pubic triangle attached to the seat, defiantly faces René Magritte’s The Rape, from 1934. In this, Hatoum and White are asking us to grapple with a history of men whose “subconscious” so often consisted of painting perky tits on sensuously shaped women. Jardin public is truly surrealist because Hatoum understands the power — and the wild juxtapostional potential — of hair: its ability to simultaneously attract and to cause severe unease, to be erotic and disgusting, to harbor memories as well as actual DNA, and fall unceremoniously away into oblivion.

‘Mona Hatoum: Terra Infirma’ is on view at the Menil Collection in Houston until February 25, 2018.