I’ve always associated Fair Park in Dallas with art. I remember going to the Ramses II exhibition there in 1989, and in my child mind the large statues of Anubis and the art deco architecture of Fair Park fit together perfectly. They both monumentalize the cultures that produced them, and like the reign of the pharaohs, it seems Fair Park is doomed unless something changes. There’s a troubled history of the Park centering around classism and racism, which feeds its current troubled state. But as a non-Dallasite, I’ve not lost the sense of wonder that came from my original Egyptian experience. This leads me to believe that art could potentially save Fair Park.

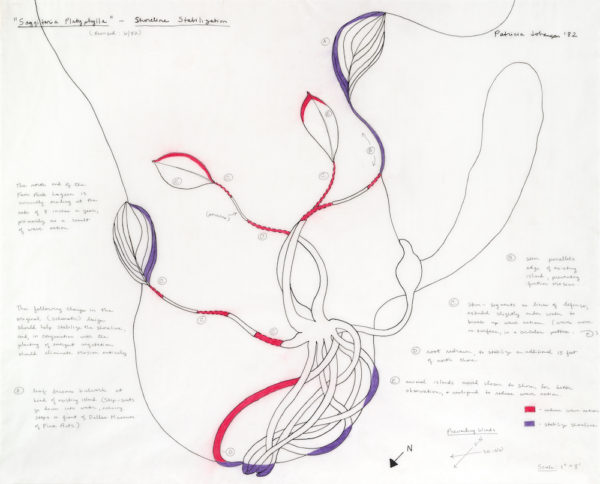

This belief is stronger due to my exposure to another work of art at Fair Park — one that seems to be virtually unknown, but is conceptually one of the most important artworks in Dallas. Fair Park Lagoon by Patricia Johanson is composed of two monumental sculptures, Pteris Multifada and Saggitaria Platyphylla, that flank the Leonhardt Lagoon in front of the old Dallas museum complex. In the early 1980s, Johanson was asked by Harry Parker, then the director of the Dallas Museum of Art (then called the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts), to restore the lagoon which was plagued by pollution, the loss of its natural ecosystem, and the occasional drowning.

Johanson worked with both the Museum of Fine Arts and the Museum of Natural History to import native species of plants and animals, and export the invasive ones. She then constructed two large terra-cotta colored sculptures undulating on the lagoon’s shoreline. Their form stems from drawings of two plants, the Delta Duck Potato and a Texas fern. The sculptures also function as walkways for the public and as a thriving environment for the lagoon’s flora and fauna. The project effectively reestablished the ecosystem of the lagoon, literally resurrecting it. Understanding this process and its history provides some hints to a possible solution to the Fair Park dilemma.

The Fair Park Lagoon is internationally known as a seminal piece in the movement of Eco-Art, and it’s one of the many impressive lines in Patricia Johanson’s resumé. She is a protégé of Tony Smith and Ad Reinhardt, and came on the scene at the height of Minimalism. She palled around with the old guard as well, including Kenneth Noland, Helen Frankenthaler, and Clement Greenberg. During this time, she became known for her extra-large works, culminating with her sculpture William Rush, which was 200 feet of painted steel beams, and Stephen Long, which measures 1,600 feet by 24 inches, installed on a defunct railroad bed in New York state. She became thrilled with the ways the works interacted with nature, and her work shifted.

Johanson began to make earthworks that intentionally integrate with the natural environment, which allows the original form and concept to evolve. She’s done projects all over the world. Her Endangered Garden in San Francisco borrows the aesthetic of the local garter snake and applies it as a walkway that camouflages a functional pump station and sewage holding tank, while incorporating habitats to nourish endangered species in the region. At a talk at Texas Tech last year, she explained that another project in Petaluma was so successful in its cultivation of natural phenomena that it has to close a trail part of the year so one of the endangered species can mate. Johanson has worked in Brazil, Korea and China, and is currently working on The Draw at Sugar House in Salt Lake City, Utah and Mary’s Garden in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Both projects employ the core themes of ecosystem creation and survival, and are still in process over ten years later.

Early on, Johanson was an assistant to Georgia O’Keeffe, who taught her to stand her ground in the male-dominant art world. To challenge the machismo rampant among some of her contemporaries, Johanson began to allow entropy into her work; she likens the limitations of the role of the creator to motherhood, and has said in the past “…the important thing is not my sculpture, but what happens to it.” Her resolve and her humble approach to art taught me that for projects that operate on a grand scale, in both time and space, the role of the artist is the anchor. We artists are the lynchpins that holds together the architects, engineers, scientists, lawyers, and accountants required for producing this type of work.

Dallas is very lucky to have Patricia Johanson’s first major earthwork. But in all the articles I’ve read on the eventual fate of Fair Park, and even the FCE report on the Park, there’s no mention of Johanson’s Lagoon piece, and its current physical state is concerning. People familiar with the fairground associate the Leonhardt Lagoon with rentable swan boats and a foot bridge that now bisects it. Most of the sculptures are fenced off and inaccessible to the public, which goes against the intention of the work. According to Johanson, “Fair park Lagoon is really a swamp — a raw functioning ecology that people are normally afraid of. …the art project affords people access to this environment, so they can find out how wonderful a swamp really is.”

Maybe this fear is behind the lack of attention of the Fair Park Lagoon, but I suspect the neglect is more financial in nature. The value of this sculpture should be included in any kind of budget for preservation of Fair Park, but what is this work worth? Johanson doesn’t have an answer for this. Because how does one determine the value of a work of art that grows and changes — one that represents an idea so broad that it can’t be quantified? (The natural response would be that it’s priceless, but this isn’t what appraisers want to hear.) The lagoon piece seems too complex for Texas capitalism. It’s easier to sweep it under the rug.

Perhaps one reason the piece is regionally unknown is Johanson’s consistently humble approach to art. She doesn’t raise hell or demand attention, and once she finishes a piece, she releases control over it. Returning to the motherhood analogy, at some point the child becomes responsible for its own existence, and this separation is part of Johanson’s process for the work. It creates an independent sustainability of the artwork, and this idea is where the true value of Fair Park Lagoon is.

The Lagoon is even more sidelined by the problematic nature of Fair Park’s history, and its current controversy. While the Park contributes to the regional economy once a year during the State Fair, it usually sits vacant. It requires a huge amount of money to maintain and operate, and this price tag goes way up if or when real restoration begins. Fair Park appears to have damaged the neighborhoods around it, and degraded their populations. In most minds, these issues outweigh a challenging work of art. But again, in the Lagoon I see a solution. The Egyptians can help illustrate the point.

That Ramses II exhibit I saw years ago contained works of art that have lasted through great spans of time. They also took great amounts of time to make. Although the true motivations of the Egyptian craftsmen who made the objects may never be known, the objects themselves represent an idea: faith in a leader — be it the pharaoh, Ra, or any of the litany of gods in Egyptian mythology. Each new ruler used this faith to take down the symbols of the old, and replace it with his (or her; what up, Hatshepsut?) own statues and temples. This creates a cycle of work, which means job creation. The pharaohs understood the cyclical economics of art, and like many rulers around the globe, they used monumental works of art as cultural engines.

The city of Dallas has a real-deal monumental work of art in the Fair Park Lagoon. The Fair Park Lagoon needs to be recognized and maintained (and please get rid of the fences, the bridge, and swan boats). It’s important because it’s a functioning synthesis of art and science, while simultaneously educating the public who enjoy it: it illustrates the natural logic of growth and change, while drawing attention to the importance of ecology to a community. Johanson’s work deserves preservation because it emphasizes the role of art in the context of urban and cultural sustainability. If Dallas highlighted this project, then it could set in motion a positive precedent for the future treatment of Fair Park as a whole.

Dallas has been coming online as a major art center in recent years, and if the city really wants to wear the art crown, it needs to recognize the Fair Park Lagoon as a jewel in that crown. Dallas deserves a monument that symbolizes the growth and change in the city.

1 comment

Very informative piece. City government has pretty much screwed it up. There’s a lot of empty buildings (science and history) and the antique train complex moved to Frisco.