The art world has been abuzz over the new large-scale drawings Kara Walker is showing at Sikkema Jenkins in New York. While I won’t see them until early October, I have been consuming all the press including a popular Facebook live analysis by Roberta Smith. Walker’s mix of savage humor, American history, sadistic sexuality and an artistically unique visual language gets audiences to look squarely at the black experience of systemic racism and the seeming intractability of white supremacism. This talent makes her current exhibition of giant drawing-based artworks the must-see revelation of the fall season.

Walker’s exhibition came to mind when seeing the excellent exhibition by New Mexico-based Michael Meads at Redbud Gallery in Houston. Meads, the subject of a major, brilliant 2016 retrospective at New Orleans’ Ogden Museum, does for the queer experience what Walker has been both celebrated and reviled for doing with the politics of race in America. Both are masters of politically charged depiction, but neither presents a pretty picture or offers a happy ending. Meads was based in New Orleans for many years and along with NOLA artists like the late George Dureau made the erotic pleasure-playground that is New Orleans their subject. The Southern Decadence celebration, a weekend-long orgy, is a favorite quick trip with a large Houston contingent who should rush to this show to see their transient joys made into the stuff of history.

Before the retrospective, Meads was best known for his photographic works: conspicuously southern shit-kickers — most not gay-identified — showing off sexually for Meads’ lens. These images were mainly harsh – guys in front of confederate flags, pointing guns, and copulating with watermelons – but there were moments of tenderness: two brothers who were previously shown in naughtier acts of boy-world affectionately hug each other. The Ogden show had a rotating slide show on a large flat screen that fixated many of us, while children were summarily kept out of the room.

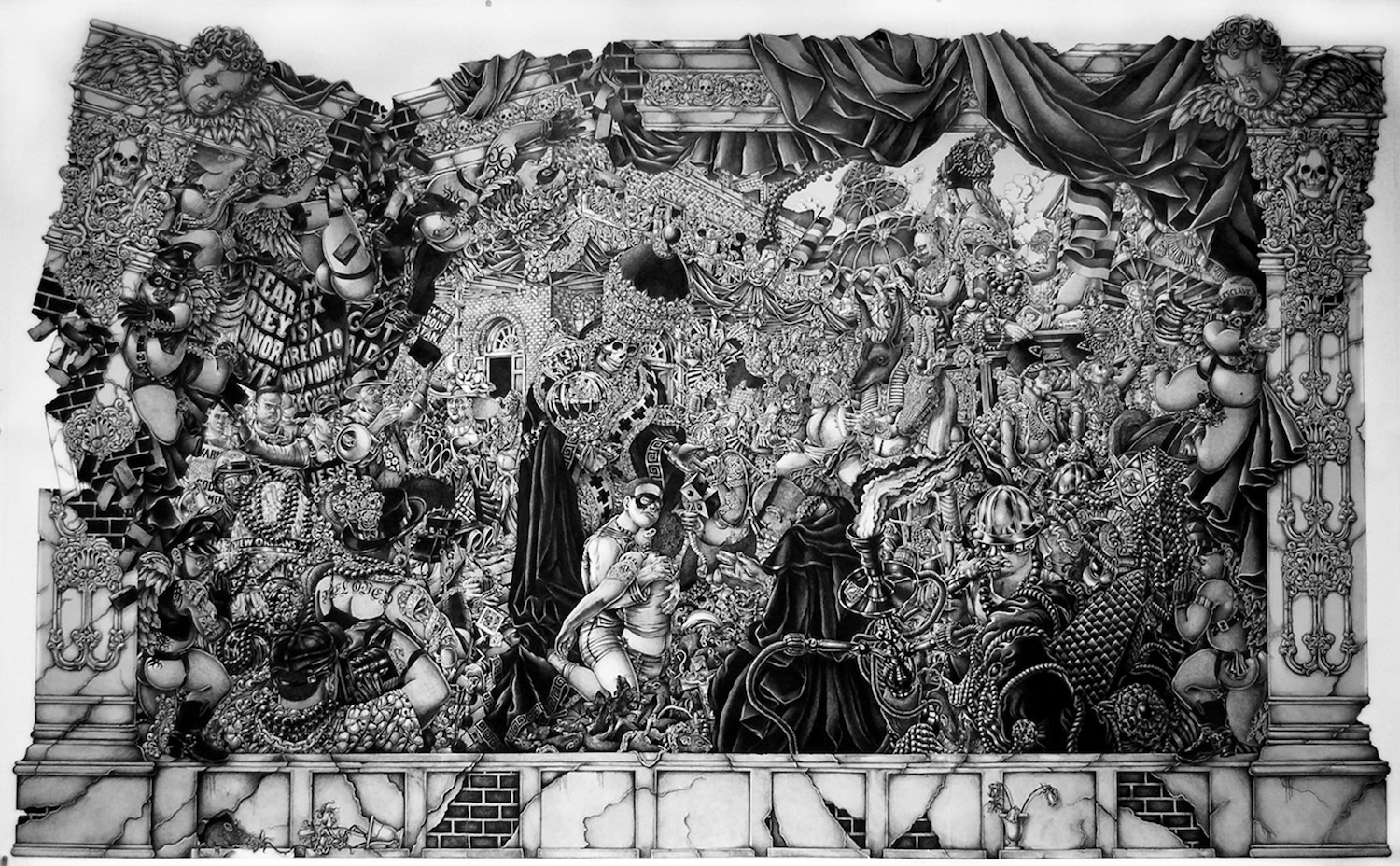

The Ogden show introduced an art form that might be the least practical for an artist hoping to sell art to make a living: massively scaled, detailed drawings. These behemoth artworks are all but unframable and hence perpetually fragile. Fingerprints, a frisky cat or a spilled coke would be enough to spell their end, but nonetheless Meads’ chosen media is inescapably beautiful. Just as Walker has chosen to use James Ensor’s Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1899 from the Getty Collection as her model for depicting the horrors of Trump’s America, Meads also conjures the spirit of the Belgian political surrealist master. As with Ensor’s great paintings, Meads recognizes no limits on how many images can be pushed into the surface. As if to prove a point, most expanses of human flesh are covered in tattoos to add a few more evocative pictures in what could have just shown a beauty mark.

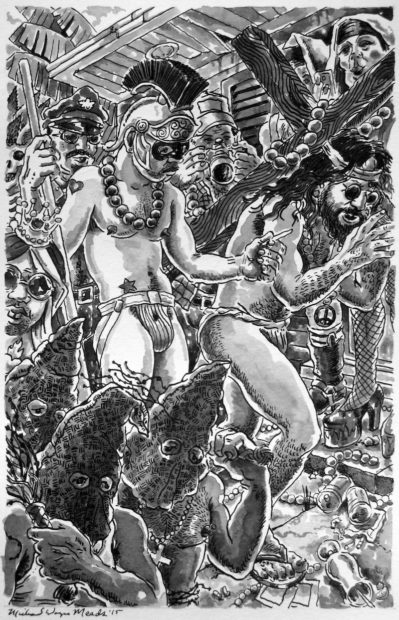

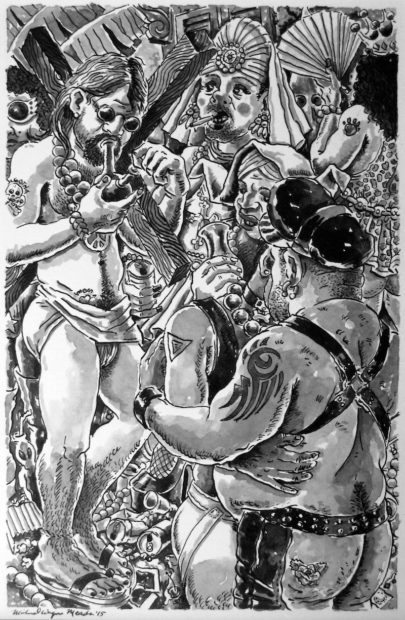

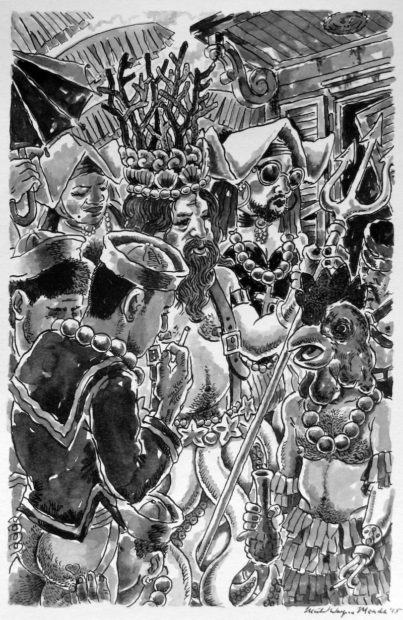

The current show at Redbud features only one of Meads’ monumental histories (no more could fit) entitled Der Liebestod, after the aria of erotic climax in Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde – a melody that has been used to indicate how music, lust, and bodily pleasures can create a divine, exquisite delirium. In this masterwork, a celebration of Southern Decadence and drawn as if by Honoré Daumier or Ensor as a mad throng of men — some clad in leather and others nude — co-mingle with Greek and Roman gods, devils, angels, and drag queens. Like Wagner’s lovers, the death drive is everywhere and each orgasm that occurs in Southern Decadence is a little blow against the puritan empire of repression. In its complete worldview, in which sex is resistance, its massive blocks of black, white, and gray feel like a Guernica for the era of AIDS.

But the specter of death doesn’t make transitory pleasures less sweet, and the central masked lover holds his partner tightly against him to keep him from collapsing. We must guess: has he drunk too much, passed out from love or too powerful an orgasm, or expired from AIDS? The difficultly of how to continue experiencing sex, love, and fraternity during an epidemic is already receding into the past. The revolutionary nature of this massive bacchanal is made clear by Meads’ inclusion of anti-gay bigots on the upper left. Like any New Orleans celebration, the only way to combat puritans and homophobes is more sex and more joy.

Young men come out and immediately get Truvada, a daily pill that removes any real risk of contracting HIV. This pre-exposure treatment has decoupled sex and death. For my generation of gay men, who can barely remember life before HIV (I was 22 when my friends started dying), this can be very disquieting — the young men we know won’t have this war-weary feeling that we have known all our adult lives. Meads’ depiction is indeed a form of history painting, and like Kara Walker, Meads must assume that for most of his audience, seeing the street outside Café Lafitte In Exile erupt into a street-filling orgy may be well outside their lived experience.

The undeniability of Meads’ topic is crucial, as you cannot even try to discuss his work without starting with queer life, the death drive, and sex. It is the topic.

There have been a number of curators and cultural critics calling the establishment cultural voices on the “progressive” argument for not discussing queer content: A recent and much-debated, three-page press release on Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ first exhibition at Zwirner that managed never to use the words “gay” or “AIDS”; or the documentary, I Am Not Your Negro, that managed to run 90 minutes without mentioning James Baldwin being a homosexual (except for a homophobic quote from his FBI file). Baldwin’s move to Europe and Istanbul was as much about wanting to lead a gay life as to escape American racism. Well-meaning progressive heterosexuals tend to take the position “We aren’t homophobic; gays have made so much progress that we no longer need to mention the gay stuff!”

Bullshit. With both Baldwin and Gonzalez-Torres, being specific helps rather than hinders our understanding of their work, and there is no risk of them being “reduced” to sexuality any more than Walker’s new masterworks are reducible to race alone. Redbud uses the text from the Ogden’s curator Bradley Sumrall that is both specific and poetic, ending with the heartbreaking phrase: “The viewer is left with the knowledge that, like Tristan and Isolde, these lovers may only be united through death.”

Michael Meads, while quite surreal in his sensibility, tells real stories that feel as much like literature as visual art. The small episodes depicted in the small drawings that surround Der Liebestod at Redbud are in many ways more legible, limited to only a few memorable figures each. But it is the courage of an artist practicing such an insane art form and succeeding that will leave you breathless. The lovers’ delirium in the face of death and bigotry is no less crazy than the insanity of this work existing in the first place.

Through Oct.1, 2017 at Redbud Gallery, Houston.

2 comments

Awesome review, Bill. Thanks for sharing your seasoned eye and personal perspective on this important work.

The tribal tattoo next to the black strap outfit thing is a good one.