Among the more impenetrable artistic mysteries percolating in this immense land mass masquerading as a mere state are the stories of long-gone songsters who brought the country blues to town. We know that Blind Lemon Jefferson could often be seen performing in Dallas’ Deep Ellum in the 1910s and ‘20s, for instance, and that Lemon sometimes supplemented his income with professional wrestling. But his lonely grave in Wortham bore no marker until 1967, an especially sad legacy for an artist known for the haunting composition “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean.”

Dallas blues researcher Alan Govenar says there are two extant photographs of Jefferson. Only one image has ever been authenticated of gospel shouter and bottleneck guitar wiz Blind Willie Johnson, despite the legions of lone-wolf researchers who stalk the ghost of his moan on the back streets of Marlin and Hearne. Some accounts say that his earthly bed of bones was located in Beaumont a few years back; others believe that the mystery endures.

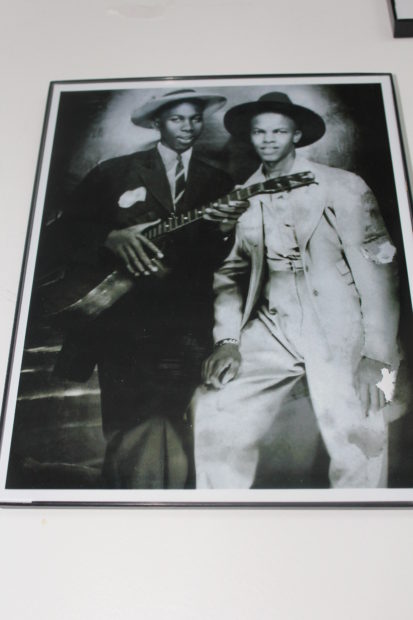

This photograph appeared in Vanity Fair in 2008, where it was identified as Robert Johnson and fellow musician Johnny Shines. Lively debate ensued, and the image has been discredited.

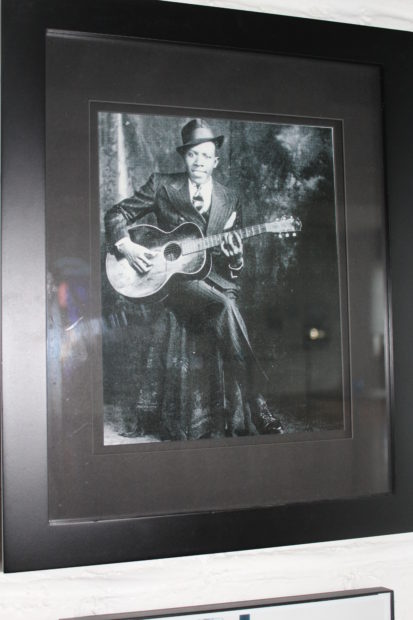

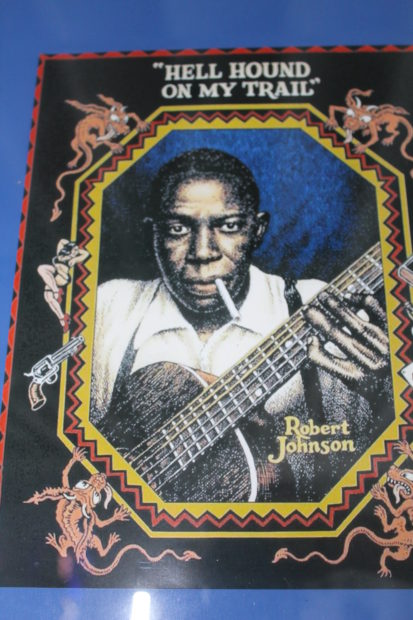

Though images and film footage continue to surface that some feel may be of the seminal bluesman Robert Johnson, only two photographs have been widely accepted. A bewildering total of three gravesites in his Mississippi Delta homeland—where legend holds that Johnson bargained with the devil to gain transcendent artistry—are each presented as his place of burial.

The immortal portion of Robert Johnson, of course, broods and beguiles and enchants in the 29 songs that he recorded in San Antonio in November 1936 and in Dallas in June 1937. And, of course, those sessions were long veiled in mystery and legend. The fact that Johnson was killed in Greenwood, Mississippi the year after the Dallas sessions further obscured his trail. According to the version most historians accept, a jealous husband gave the charismatic bluesman some poisoned whiskey.

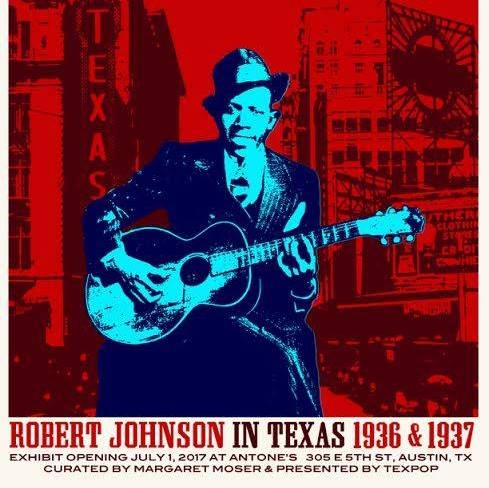

I learned that story in wall text for Robert Johnson In Texas, an exhibition of images and artifacts in the upstairs room at Antone’s, the latest iteration of the august Austin blues club founded by Clifford Antone in a distant century. Curated by longtime music writer Margaret Moser and produced by San Antonio’s South Texas Center for Popular Culture, the exhibit gathers wisps and glimmers of the songster’s fugitive saga and summarizes recent-ish discoveries and near-discoveries, and loving gestures of homage.

Lydia Mendoza at the Bluebonnet. Moser’s exhibition opens a window on 1930s San Antonio, its musical landscape, and its importance as a regional recording center. Lydia Mendoza recorded in the Bluebonnet Hotel.

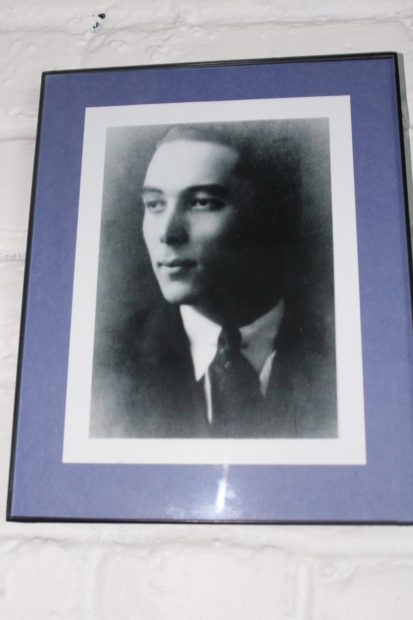

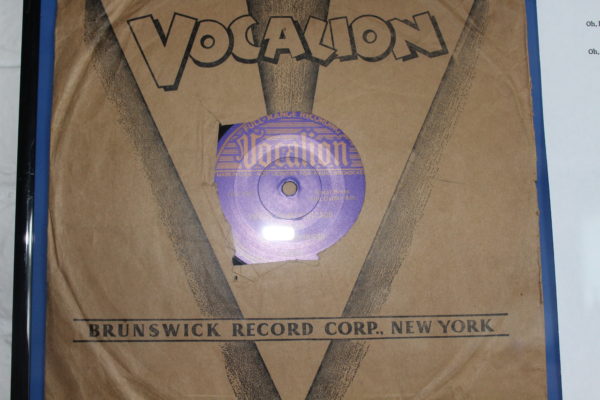

The minor uncertainties about the location of Johnson’s San Antonio sessions are represented by Bluebonnet Hotel memorabilia and a fiery image of Lydia Mendoza recording at the Bluebonnet. Wall text notes that the book Saving San Antonio places Johnson’s Alamo City recordings in the Bluebonnet. (Footnotes in the book cite a 1986 San Antonio Express-News story headlined “Blues Wizard’s San Antonio Legacy.”) Saving is one of my favorite San Antonio history books, but the wizard most likely rambled through the hallways of the Gunter Hotel to room 414, where the young and handsome Vocalion Records producer Don Law recorded Johnson’s performances of “Terraplane Blues” and other songs.

Booklets of Gunter Hotel history from decades past include nothing about the landmark recording session of 1936, but today the Sheraton Gunter Hotel welcomes guests to its Bar 414 with large reproductions of the ubiquitous photograph of Johnson playing guitar and looking snappy in a suit, tie, and fedora. Bar 414 drinks are named for the bluesman’s songs. At the Antone’s show, the Gunter is recalled with a room key, vintage matchbooks, and postcards.

Other graphics and images depict 508 Park, the downtown Dallas building where Johnson recorded “Hell Hound On My Trail” and other tunes in June 1937. It had long been believed to have been the site of the recording sessions, but it wasn’t definitively confirmed until a 1961 letter—a photocopy is included in the exhibition—surfaced in a New York basement in 2006. The letter was written by Columbia Records employee Frank Driggs to Don Law, as Driggs was preparing liner notes for the 1961 Johnson album, “King of the Delta Blues Singers.” Law answered Driggs’ questions in longhand on the typed letter. In addition to confirming both the Gunter and “a makeshift studio” at 508 Park as the recording session sites, the letter reveals that the artist was picked up by San Antonio police his first night in town, “beaten up and thrown in jail on a false vagrancy charge.” Driggs then typed: “He was around 18 years old [sic] at this time. You got him a room in a boarding house in the Negro district and you gave him forty-five cents for breakfast and he called you at dinner with that story [about being lonesome and needing five cents],” asking Law to dictate exactly what was said. Law added in handwriting: “There is a lady here. She wants fifty cents and I lacks a nickel.”

Recalling what Law had previously told him about the session, Driggs typed: “You said he was quite shy, because you wanted him to demonstrate his guitar playing for some Mexican talent you were recording.” Law handwrote: “He reluctantly complied but sat on a chair in a corner facing the wall,” presumably to guard the secret mojo of his technique. The original letter is now preserved in the Library of Congress.

Previously in danger of a date with the wrecking ball, 508 Park—described as Dallas’ prime extant example of the Zigzag Moderne architectural style—has been saved. I’ve long wished that my hometown of Dallas would more proactively and professionally preserve and interpret the rich cultural legacy of its Deep Ellum neighborhood. And though 508 Park is not in Deep Ellum, the plans for the site, when fully realized, will be a tremendous asset for the city.

Encore Park Sculpture Wall. Blues musician Keb Mo gesturing to Robert Johnson in panel. Photo: Jeffrey Liles

Named Encore Park, the 508 Park redevelopment and preservation effort is an outreach project of The Stewpot homeless facility (across the street from 508 Park) and the First Presbyterian Church of Dallas. Two outdoor components of the project have already been completed: the 508 Amphitheater and the Encore Park Sculpture Wall. Created by artists Brad Oldham and Christy Coltrin, the lost-wax bronze sculpture wall includes ten 6-foot by 4-foot bas relief panels—some based on a lost Depression-era mural by Jerry Bywaters and Alexandre Hogue—that depict the story of Dallas into the 1930s. Robert Johnson appears in two panels, and in one he is joined by the Light Crust Doughboys, who also recorded at 508 Park back in the way-back day. Future interior plans include the Museum of Street Culture and a 1930s-style recording studio that will show how Robert Johnson and other artists cut their sides.

When the Johnson exhibit opened in San Antonio last year, curator Margaret Moser described his Texas recordings as one of “the most essential chapters of American history.” Moser herself, as a chronicler of late 20th- and early 21st-century American music, has had a front row seat to head-spinning volumes of more recent essential chapters. After ending cancer treatment and entering home hospice care several weeks ago, she has been schooling friends and fans on how one prepares to travel on with bravery and grace. As musician and writer Jesse Sublett described her presence at the Antone’s opening, “Everybody was there for Margaret Moser. And I mean everybody.”

But Margaret, I’m sure, would say it’s the music. And Robert Johnson’s astonishing recordings in Texas in 1936 and 1937, documented in this exhibit, laid much of the groundwork for the blues-fueled rock’n’roll that was discovered by my teenage musician friends in the Big D ‘burbs of the 1960s. At the time, we pretty much accepted that it came from the so-called British Invasion – it would be many years before we even imagined that much of it was recorded right downtown, three decades earlier, by an amazing black guitarist from Mississippi.

****

“Robert Johnson was like an orchestra all by himself,” testified Keith Richards. “Some of his best stuff is almost Bach-like in construction….a brilliant burst of inspiration.”

“When Johnson started singing,” added Bob Dylan, “he seemed like a guy who could have sprung from the head of Zeus in full armor”

****

Read the 1961 letter: https://www.scribd.com/doc/11129232/20090122125042109

**

‘Robert Johnson in Texas’ is at Antone’s, Austin through July 24 by appointment, or ask the Antone’s staff to open up the second floor to see the exhibition. Email [email protected].

3 comments

Well done sir!

As always you take me to see things and experience them in a special way that I can’t experience fro way “out here” in west Texas.

Thanks!

An amazing, thoughtful article!

had to listen to some: Spotify ” Cross Road Blues “has nearly 7 million requests