In East Texas this summer, in the cozy space of the Tyler Museum of Art, there’s a small show of works by Texas artist Ed Blackburn. It’s a sampling of drawings, prints, and a few paintings from the early 1980s that source iconic movie stills from Hollywood’s classical age. Double Take, organized by the museum’s curator Caleb Bell, is billed as the first museum retrospective of Blackburn’s “Movie” works. There is an accompanying film series open to the public, and it would seem a lighthearted and accessible show, perfect for summer. But that view may not prepare audiences for the bigness of Blackburn’s work, or his significance as one of Texas’ more important living artists. Born in Amarillo, he has been a significant artist since the 1970s and, luckily for us, has chosen to hunker down in his home state all these years rather than hop on the well-paved roads to one of the coasts.

Blackburn himself is likewise modest and unassuming, and could easily be mistaken for a regular, good-natured person; in fact, he’s a wizard, with deep knowledge of the universe. Most of what I’ve learned about how to sit with a painting and get to know it came from group critiques he led at UNT. He will sit wordless for minute after minute, giving the piece on the wall time to unfold before gently undressing its aesthetic structure.

Blackburn’s mild-mannered demeanor hides other unpredictable moves in his work. He’s dealt with the material and styles of current political events, film noir, comic strips, and Bible stories, none of which end up schlocky or dated. This series based on film stills also transcends the celebrity and iconography of its sources to directly address modes of seeing affected by the moving image. It plugs into conversations around media and narrative, but takes on these subjects from the vantage point of Painting, with all the ontological and phenomenological insights the discipline can offer. In fact, for as complicated and processed as his source material is, he translates it with utter clarity, into the kind of real-time experience with an object that moving images tend to erase.

Painting No. 8, 1986, Oil on canvas, 78” x 100”. Tyler Museum of Art General Acquisition Fund, 1987.

The half-dozen large paintings on view here are loose, unfinicky, and yet accurately portray faces and gestures without any cross purposes. Painting No. 8 is nearly wall-sized and done in grayscale. It’s Gregory Peck in a suit and dark shades hunching over a CB radio. Between his manly knuckles, the steely eye behind dark glass, and the words dangling off his lip, you almost know the whole plot. All of this comes through loud and clear, but the brushwork animates everything. The texture of celluloid is analogized by the swirling wetness of paint. It moves and breathes, and it hides nothing: rather, it expands the image.

Painting No. 2, 1984. Acrylic on canvas, 52 1/2” x 59 ½”. Courtesy of Museum of Texas Tech University.

Painting No. 2, takes up around 4 X 5 feet of wall space, but feels wide open. Frank Sinatra and Debbie Reynolds in a cutesy embrace occupy most of the frame; he a little more centered than she, and his eyes focused forward while she bats hers up at him. Blackburn allows us to “get” all of this while making it fresh. Primary colors are layered up gesturally; bits of white canvas laced throughout. The picture is all built out of the same light, the same color particles. The way it’s put together directs, sequences, materializes our viewing. It hits this sweet spot where it nearly falls apart as a picture, almost unravels, but just holds together.

False Colors, 1982. Graphite on paper, 22 1/2” x 30 1/2”. Collection of Betty Moody, Houston, Texas.

The small works are also nice. They seem to carry more weight than their size would suggest. The basicness of their ingredients is refreshing and clean. And they have that worked-out synchronization of the mark-making with the thrust of choreographed drama.

One of Blackburn’s strategies noted in this show was developed in earlier work, in which he reverse-engineers the three-color printing process and injects his own hand into the space flattened by the camera. Or maybe it’s that he picks up the language of mechanized images, and folds it back into the deliberate and mindful practice of painting.

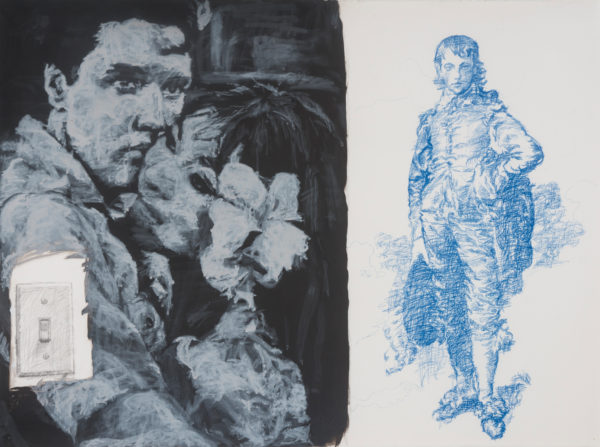

Elvis Movie with Blue Boy Wall Drawing, 198. Acrylic and pencil on paper, 22” x 30”. Collection of Cece and Ford Lacy, Dallas, Texas. Photo credit: Harrison Evans.

There’s something visible in these images not found in their sources. They are more real in these built-out iterations than they are dancing on a big screen. They don’t preach—they win you over optically—but if there is a moral packed into them I think it has something to do with the humanness of media, the spaces opened up by stories and accessed by a joint action of vision and thought. They demand that seeing isn’t easy or passive; it’s an intellectual and physical endeavor. Blackburn doesn’t deconstruct the image to find some truth lost in its transmission. He knows that the truth of an image is in the receiving of it. The title of the show, Double Take, asks us to take a second look. I recommend staying for a third.

Through August 20, 2017 at the Tyler Museum of Art.

2 comments

This is a very accurate and compelling review of Ed’s paintings and practices.

Thank you.

“In fact, for as complicated and processed as his source material is, he translates it with utter clarity, into the kind of real-time experience with an object that moving images tend to erase.”

Great sentence. So relevant. This could easily be a way to explain the importance of much great painting and sculpture.

Michael Frank Blair really nailed it with this clear and insightful review.

Ed Blackburn is the best. An artist with a unique perspective. I’m glad that I had the opportunity to study with him as a graduate student at U.N.T.