The press release for this show benignly states: “This new body of work draws from an extensive visual vocabulary of African diaspora and contemporary American experience.” But Anthony Suber’s work at Cindy Lisica Gallery in Houston is more specific and corporeal than that. Ritual Redux establishes the African diaspora as the ancestral through-line to how a black body is perceived, encountered, and picked apart in America today—a body that is alternately feared and awed, digested and churned into a cultural punchline, admired and discarded. In what way does betrayal, a sense of belonging, oppression, resiliency, connectedness, anger, frustration, dislocation, and joy pulse through a bloodline, and how can we feel that through materials?

This is Anthony Suber’s mission, and it’s important that everything in this show is bodily, and paradoxically, we feel the myriad ways in which history and culture inform and are carried within the body most poignantly when the work is more materially-based and less figural. The major exception here is also the earliest work, the focal point and star of the show, and presumably the birthplace of Ritual Redux: Medium (Shaman) (2014). Eyes shut, an oxidized face emerges from a scorched-earth wooden base, mounted like a hunting trophy. We don’t know if the gold was smeared upon or emanating from the lower half of the face, but we do know that it is guarded by and trapped within a conical structure of metal rods collapsing under the weight of its own confrontational apparatus—like a slumping elderly man or a failing erection.

The essence of materials may be at the crux of this work, yes, but Ritual Redux is at its best when Suber confounds the viewer with the possibilities of the very materials he uses. Utilitarian objects like wood and metal become painterly; echoes of the body meld into infrastructure. No. 30-33 (all 2017) hang along the left wall from the entrance like sculptural shields or stop signs, signed at the bottom as if intended for mass dissemination. In the center of these four works floats an object at once ovarian and tribal—perhaps a mask that could be celebratory or armor. The small choices Suber makes in relation to each centralized object in this series transforms the work from decoration referencing a visual vocabulary of the African diaspora to viscerally linking the structural to the corporeal. A bleed of oxidized pigment here, the decision to polish or not polish the wood there, oil invading the boundaries of white space like a pit stain: this series invokes the silent history of a rusted bridge or a tattered undershirt. Stained wood and oxidized metal play off each other, enriching the deep browns and reds inherent in both, evoking the regenerative and decaying qualities of soil.

No. 29, 2017, Acrylic, oxidized metallic pigment, laquer, gold and copper leaf on Masonite, 12 x 12 inches

No. 28-9 (both 2017) have the same kind of mask-like figure as the focal point of each work. But held up against a stark-black background, they read more like satellites or apparitions. Splotches of gold and copper leaf sparkle like starlight or blood splatter.

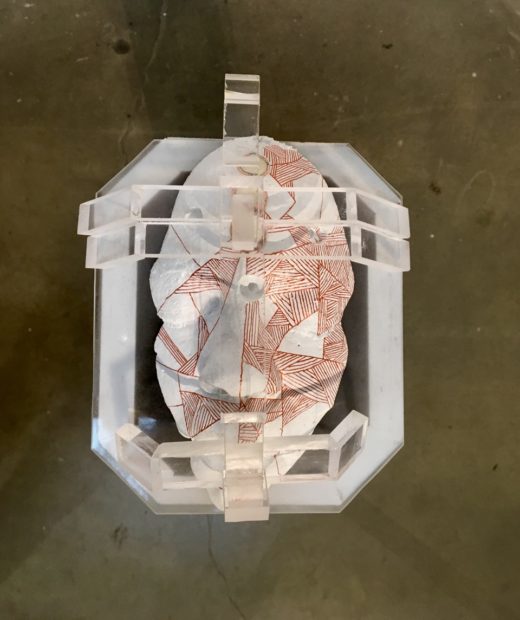

The Refraction Mask (all 2017) series similarly glows, but in a more literal and heavy-handed way. Here, actual masks rest atop custom-made pedestals that glow from within. The white masks are decorated with tribalesque copper lines replete with Plexiglas shields or outgrowths. While these works ask us to consider the body—particularly the African body—as a kind of display or commodity, the fragility of the mask in combination with the hardened glow of the LED lights and the literal hardness of the Plexiglas send us into Robocop sci-fi territory. It’s a narrative that ultimately points to or tells us how to read the story instead of possessing the quiet confidence and deep empathy of the wood and oxidized pigment.

Anthony Suber lays bare the vibrancy of a black body and the deeply rich and layered and complex history that it harbors. As we excavate those layers as viewers, Suber asks us to consider that history and this body as fragile and immovable, resilient and scarred.

At Cindy Lisica Gallery until July 1, 2017.