José Clemente Orozco, The Women Soldiers (Las soldaderas), 1926, oil on canvas (óleo sobre tela), Museo de Arte Moderno, INBA, Mexico City.

The Dallas Museum of Art’s hyped exhibition, México 1900–1950: Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, José Clemente Orozco, and the Avant-Garde is the baby of new DMA director Dr. Agustín Arteaga. It collects the modernist impulses and investigations of the country’s cultural upper-class just after the turn of the last century, and with the backdrop of the Mexican Revolution. The show is a sampler plate of compelling artists, some you know and some you may not, with square footage given to a lot of lesser-known work. Most importantly, the show begins to tell the story of Modernism in a new way, and it’s one we all would benefit from knowing.

The exhibition is divided into two timelines, in two languages, on two floors of the museum. The dates and events map artistic and political upheavals surrounding Mexico’s Revolution, tracing the cracks formed when an Arts apparatus falls out of line with a ruling body. Painting is the focus here, but with scatterings of photography, prints, film, and sculpture, and the picture that begins to emerge is of a country turning its sights on itself and finding reason to fall in love.

My own love affair with Mexico bloomed because of its stark contrast to my white-bread West Texas upbringing. While taking some college courses there and traveling around a bit, the art and literature I drank in seemed to connect more urgently with social and political realities. It felt more direct and dangerous; funnier, and more human. There was more death and more life, and way more color. Through the fresh eyes of a foreigner is how many of the artists in this period began to see their own country.

Organized into consecutive rooms that group works under themes such as: “Mexicans in Paris,” “Archetypes of Indigenous Society,” and “Strong Women,” and by movements such as Surrealism and Magical Realism, the work takes shape in a familiar arc. It reaches back to European-style academic painting as a starting point and then charts the way those cultural conventions were questioned, transgressed, dismantled, and uncoupled from the stink of colonial power. It’s also a story of urbanization and industrial growth; of communist dabblings and of national identity being sought in the soil rather than the palace regalia.

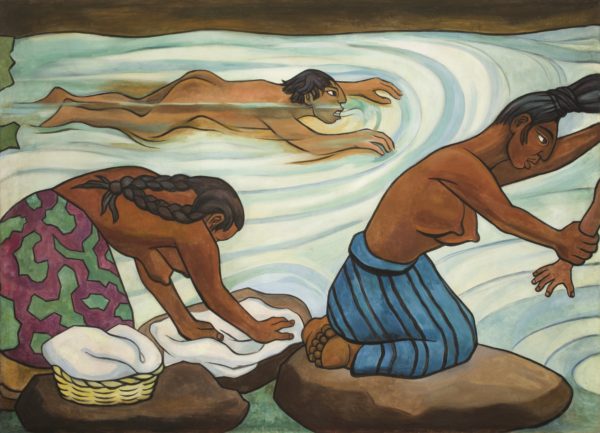

Diego Rivera, left panel detail from Juchitán River (Río Juchitán), 1953–1955, oil on canvas on wood (Óleo sobre tela adherida a madera), Museo Nacional de Arte, INBA, Mexico City.

Spain’s colonial experiment in Mexico carried out domination differently than that of the U.S., and led to different (though no less problematic) notions of identity, race and cultural authority. Mexican artists have long tried to rewrite phenotypic codes, using the aesthetic tools at hand. Saturnino Herrán’s Nuestros Dioses (Our Gods) from 1918, which is easily the flashiest and most breathtaking painting in the show, takes one approach. It’s a long panel (the left panel of an unfinished triptych) crowded with the lean bronze bodies of young Aztec men. They crouch and kneel like Greek gods lugging offerings of fruit, adorned with feathers and gold, all foregrounding a truly epic mountainscape. The connections are clear here: Herrán is proclaiming the majesty of indigenous bodies by funneling them into classical forms. Other artists settle on a less Western stylization, embracing thicker, flatter forms that draw from folk traditions and pre-Columbian sources. Diego Rivera’s Juchitán River is a panorama of this new figurative vocabulary.

For obvious reasons, there’s little to see of the large murals by Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and Davíd Alfaro Siqueiros, aka “The Big Three.” But many of their easel-sized works and small sculptures are threaded throughout. This puts their work on equal footing, scale-wise, and still gets the import of their contributions across: from Orozco’s vocabulary of violence, to Siqueiros’ fixation on the workers’ struggle, to the facility and breadth of Rivera’s vision.

There are examples from the many stylistic movements that sprung up as artists trekked back and forth through Paris, New York, and elsewhere—bringing back aesthetic experiments to play with at home, and no doubt leaving ideas of their own abroad. One of the cultural mechanisms of Modernism has to do with the interfaces between a nation and a larger world: not just trade relations but also the media technologies that literally allow a people to “picture” that larger world, and more importantly, images of themselves through the eyes of that outside consciousness. It involves inverting the self/other dynamic by finding and exoticizing an “other” in some aspect of one’s identity. Picasso looked for it in Africa, Klee in the child, and Dubuffet in the asylums. The Mexican artists performed a sort of self-archeology. Rivera and co.’s program was to forge a “national soul” celebrating Mestizo identity. Cacti and magueys become wonderful stand-ins for the “land” as a mute being. They’re strange, lunar, alien. But most often it is women’s bodies bearing the symbolic burden. They’re often made to personify La Patria: its beauty, its innocence, its origins.

Olga Costa, Fruit-seller (La vendedora de frutas), 1951, oil on canvas (óleo sobre tela), Museo de Arte Moderno, INBA, Mexico City.

The room of “Strong Women” makes a case for the work of women who are usually overshadowed by male counterparts: husbands, colleagues, lovers, etc… . We all enjoy a turbulent love-affair, and the bohemian soap operas of Frida and Diego, Edward Weston and Tina Modotti, or Dr. Atl and Nahui Ollín (born Gerardo Murillo Coronado and Carmen Mondragon) ooze with intrigue. But the practices these women artists carved out for themselves, while also having to play the part of model and muse, can’t be understated. They seem to bring to their role as depicters a sensitivity to their subjects’ interiority. Contrast Rivera’s iconic Flower Seller with Olga Costa’s Fruit Seller. Rivera’s woman sits object-like, dignified in her posture but faceless. Costa’s woman is a full-fledged personality, meeting our gaze from behind piles of impeccably arranged fruit. Frida Kahlo doesn’t disappoint. Her eccentricities are grounded in a real purposefulness. She’s awkward and intense in all the right places. And Ollín, who’s haunting eyes are the subject of many paintings and photos in the show, also paints things from her powerful point of view. Her self-taught style recalls Marc Chagall, but is both stranger and sexier.

Frida Kahlo, Itzcuintli Dog with Me (Perro Itzcuintli conmigo), c. 1938, oil on canvas (óleo sobre tela), Private Collection, Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico.

There is a lot to see here, and the story presented is one we don’t often encounter. This is a Modernist drama. The work couldn’t be more important. We need to dive in, flinch and squirm, detangle and deal with the complicated and achingly beautiful country of Mexico as part of our own story. As walls are set to go up, we’ve got to continue sewing together our histories and humanities with needle and thread, knowledge and humility, and even some romance. We need to practice new forms of defining our collective selves. We need to find new ways of falling in love.

‘México 1900–1950: Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, José Clemente Orozco, and the Avant-Garde’ through July 16 at the Dallas Museum of Art.