With International Discoveries VI, FotoFest in Houston draws together thirteen emerging artists, many exhibiting in the U.S. for the first time, who grapple with the conceptual and material particularities of photography. Each artist represents a “discovery” made by FotoFest’s curatorial team—Steven Evans, Jennifer Ward, and Wendy Watriss—at portfolio reviews, studio visits, and photography festivals across the globe. International Discoveries IV represents the most recent iteration of an exhibition series conceived as an international platform specifically for emerging artists within the field of photography, and it’s presented during alternate years to FotoFest’s sprawling, city-wide Biennial.

Dai Xiang (China), The New Along the River During the Qingming Festival (detail), 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

It’s an impressive display of new talent. The New Along the River During the Qingming Festival gives a panoramic view of a meandering river along which everyday scenes unfold. Staged by the Chinese artist Dai Xiang, the photograph spans nearly 33 feet and is a contemporary iteration of a famous scroll painted by the artist Zheng Zeduan in the 12th century. Zeduan’s earlier scroll encapsulated the people’s historic daily life along the winding the river. Xing’s newer version, meanwhile, is composed of a mosaic of scenes depicting contemporary life, and points towards a growing discontent with the ascendance of consumerism and modernity in China. In re-imagining a canonic painting from China’s past as a photograph, Xiang brings into focus the medium’s ambiguous relationship to history. Since its invention, photography has shaped our recollection of the past while often influencing a path of progression. This feeling of ambivalence towards technological innovation and society’s seemingly insatiable hunger for progress is a recurring theme within the piece.

In Xiang’s river landscape, we see scenes of protests against rising property prices, state corruption, and, in one case, the public shaming of a butcher for selling tainted meat. The scenes portray the people’s real, everyday struggles while cultivating a kind of staged presentation that contemporary viewers increasingly expect from their entertainment. Xiang invokes an awareness of the constant presence of the camera in our lives—one that erodes the line between being and performing in the world.

This blurring is echoed in the work’s construction. The New Along the River During the Qingming Festival appears as a single photographic print, but is in fact a compilation of more than 1000 images. The artist has inserted himself in a multitude of roles and representations of the population, which Xiang manipulates into a ‘single snapshot’ as one seamless landscape of impossible perspectives. Xiang’s river of images underlines a current condition of the medium; as the ubiquity and interchangeability of images accelerate, photography’s content and meaning grow more slippery.

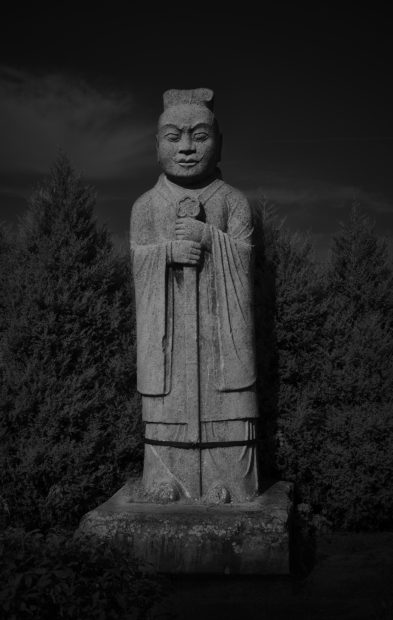

Qian Jin (China), Tang Qianling NO.5, from the series Dynasty In Stone, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

Chinese artist Qian Jin uses photography as a means to expose subjects obscured from our collective consciousness. His series Dynasty of Stone captures ancient stone statues erected during the Chinese imperial dynasties from 221 BC-1917. These statues were once the guardians of the tombs of emperors and the Chinese ruling class, and represented the vast reach and prestige of the empire. They’re now littered throughout the countryside, fading into the landscape and seemingly lost in time, and Jin traveled extensively to locate and photograph them. The artist uses elaborate lighting techniques to emphasize the sculptures’ solemn dignity, and the resulting images capture the sculptures in what seems like a perpetual dusk, guarding a faded history that refuses to completely disappear.

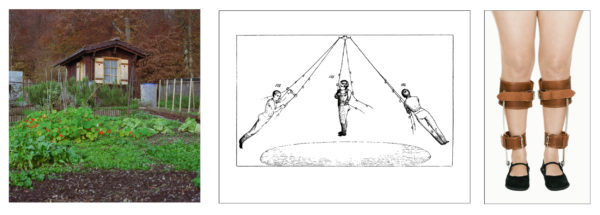

Paola Dávila (Mexico), Chapter II. Second to Seventh Year of Life. Playing Years. Physical Aspects. Movement. From the series Schrebergarten, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Patricia Conde Galería, Mexico City.

Similarly, Mexican artist Paola Dávila’s project delves into the little-known history of the Schrebergärten. Part of a movement that sprung up across Europe in the wake of the industrial revolution, these communal green spaces were conceived as a way for the middle classes to ‘reconnect’ with nature. Moritz Schreber, the spiritual father of the movement, was a 19th-century Swiss doctor who advocated a return to nature as part of his Spartan vision of child rearing. Instead of places of play, Dr. Moritz envisioned these gardens as sites for children to build character and stamina through the hard physical labor of cultivating the earth. Davila’s photographs of small sheds perched in idyllic patches of green offer no clue as to their darker origins, and this ambiguity is reinforced by the artist’s photographs of Dr. Schreber’s’ orthopedic devices. Based on the doctor’s drawings and texts, the artists has recreated various torturous-looking contraptions. Designed to force the children’s bodies into a proper or ‘natural’ shape, as deemed by the doctor, these devices are another example of how Dr. Moritz attempted to control nature. By exploring this history, Dávilla questions our preconceptions what is natural. How can we understand nature, including our own bodies, when the world around us is constructed after an idealized image?

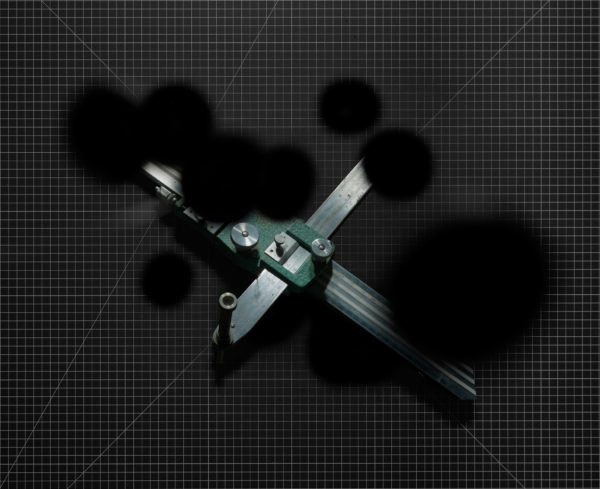

The lingering uncertainty of what is “real” and what isn’t is a reoccurring subject in the work of American artist Tad Beck. In Blind Spot, his series of photographs of photographs, Beck plays with the illusion of photography, as well as the viewers’ expectations of it, by using spray paint, darkroom dodging tools, and photographs of arcane hand tools to manually create the illusion of heavily photoshopped images. The work challenges us to consider the tools that shape our perception while forcing us to recognize our limited knowledge of how certain images get made.

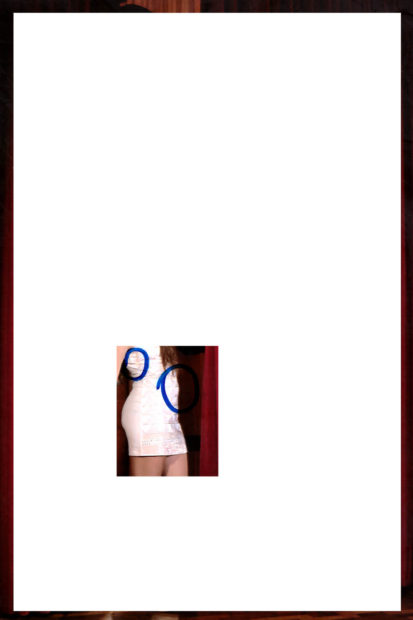

In a more direct way, Brazilian artist Tuany Lima focuses on the consequences of our ability to manipulate images of the world and ourselves. Under the ‘dictatorship of beauty,’ as she calls it, Lima’s series Áurea shows details of photographs taken at a the debutante ball—a tradition in Brazil’s upper class. In fragments redacted from a bigger picture, we see parts of women’s bodies in fancy dresses with details marked or circled with a Sharpie; these marks were made by the young women themselves, to indicate which parts of the their bodies they would improve for photo reproduction. For Lima, the camera is a dictator’s tool, but if we’re experiencing a kind of totalitarian regime of the photographic image, what does it mean that we point the camera increasingly at ourselves?

****

Discoveries IV will be on view at FotoFest International Houston until March 18th.

It includes work by Tad Beck (USA), Ilana Bar (Brazil), Dia Xiang (China), Paol Dávila (Mexico), Favio Del Re (Brazil), Qian Jin (China), Jung A. Kim (Korea), Hyunmoo Lee (Korea), Tuany Lima (Brazil), Eustáquio Neves (Brazil), René Peňa (Cuba) Marcel Ruis (Mexico) and Zhang Kechun (China).