I first encountered Hermann Nitsch’s work at the Slought Foundation in Philadelphia in 2008 when it hosted a retrospective of his work. Nitsch has exhibited and performed prolifically and internationally for the past 50 years, and as a founding member of the Viennese Actionism movement and collective of the 1960s, and founder of the Theater of Orgies and Mysteries, Nitsch’s work is considered some of the most extreme performance and body work ever created, due to the rituals involving blood, sex and violence. The videos are challenging and disturbing to watch. I thought after an eight-year hiatus, I would be able to sit through some of it at the current Dallas Biennial (DB16) at the Box Company, but that wasn’t the case.

I have great respect for Nitsch’s importance to art history and his ability to sustain such a generative practice over five decades. It’s important to understand the cultural context post-WWII in which the Viennese Actionists were responding to the atrocities committed during the war. It’s also important to recognize the influence that Nitsch has had on subsequent generations of contemporary performance artists and art history as a whole. There’s an intensity and immediacy to his work as it relates to religion, the body and historical trauma. His performers and followers dedicate their bodies to participate in sacrificial and hedonistic blood orgies. They trust in the artist and the process.

So while I couldn’t watch a lot of the video on loop at the Box Company, I spent considerable time looking at the installation of paintings and ephemera created during and after the performances. Beautiful abstract canvases and relics painted with blood lined the walls surrounding the video room. Installed as triptych alters, the works reference Middle-Age Christian painting and notably point to the bloody history of Christianity. The large video room is boxed off from the rest of the warehouse gallery. This is not only utilitarian from a visibility and light perspective, but it also doesn’t force visitors to confront the video directly; they’re able to enter and exit on their own volition. Another component to the videos is the sound; haunting organ music reverberates throughout the gallery creating a solemn and sacred mood in the space.

But this is a two-person show. And one of my questions before going to see it was about the relationship between Teresa Margolles’ and Nitsch’s work, beyond the obvious material/process commonality of blood and performance. Learning that Nitsch was a big influence on the younger (and acclaimed) Mexico-based Margolles concretized the relationship between the artists’ work, and while grounded in performance and ritual, Margolles also addresses current socio-political themes, most prominently involving victims of murder. On exhibit are four of her installations, two of which were created specifically in Dallas for the gallery.

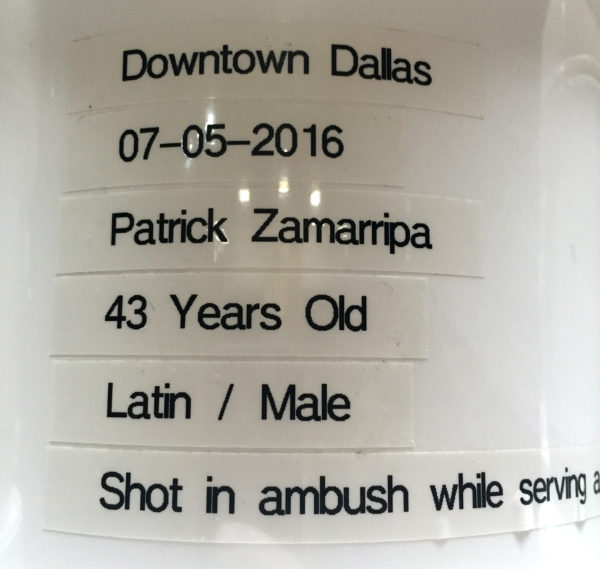

Margolles’ site-specific Dallas works document the exact number of murders committed in Dallas in 2016. Margolles and a team of artists visited each of the murder sites and conducted on-site performative cleansing actions. The ‘wash’ water from each of the performances was collected and put in a generic white plastic bucket labeled with the name of the victim and details about the murder. A majority of the victims were non-white males. The work functions as a documentary and visual archive of the victims, as well as the ephemera from the cleansing action—one that is designed not only to erase any traces, but in my mind to create a eulogistic homily to honor the victims and their families.

Another Margolles work is a subtle intervention of the stairs that lead from the gallery entryway into the main space. These concrete stairs are unexceptional until we learn that we’re stepping on the imprint of cement dust from all the murder sites in Dallas. This act implicates the viewer as an unwitting and unknowing accomplice to the violence.

There are bubble machines that fill the grand recessed entrance with floating suds; it’s audience spectacle and celebration. It reminds me of a dance floor in a NYC circa 1982; the machines churn out thousands of bubbles defining and then popping in the space. Then finding out that the bubble water is from the same wash water from the murder sites is sobering.

In the back of the gallery hangs Margolles’ very long ornate tapestry created by artisans in Bolivia. The fabric is stained and imprinted with the blood of female murder victims and visual references the rampant violence against women. The tapestry is beautifully constructed and embroidered with attention and care, while the bloodstains permeate the fabric.

But one of the most important aspects of the show is the gallery space itself. Located in an industrial area of Dallas south of downtown and I-30, in a former cardboard-box production building, the raw, barren, and unheated warehouse provides an additional layer of contextual meaning to the artists’ work. I arrived on one of the coldest days of the year and the Box Company co-founder Jason Koen, bundled in a parka, gave me a guided tour. Knowing the history of the site and the fact that it was owned by the Koen family for years (Jason worked at the box factory as a teenager, and has witnessed the neighborhood change over time), added an additional element of specificity and relevance to the artists’ work. Koen told me that when he was younger, bodies were sometimes found nearby on the streets. He remembers vividly one case where a presumed prostitute was murdered, mutilated and left on the adjacent railroad tracks. He pointed out areas of the warehouse that had been riddled with bullet holes. As a testament to both regional violence and violence in general, the Box Company site, as a kind of memorial for victims, is much more visceral than a sanitized white-wall art space.

My main criticism with the show is its lack of accessibility by the public. The press release was missing contact information and I had to hunt down the organizers to get access. The show should be made available to more than just the select art crowd in Dallas. When the Slought Foundation showed Nitsch’s work, it knew there would be pushback about its content, and ensured that there was a lot of online and accessible written information to give viewers a chance to better understand and engage with the work, as well as hosting panel discussions, and inviting local university students to participate in the dialogue. Nitsch and Margolles have plenty to show us, however difficult the message, and the more people who experience it, the better.

DB 2016: Teresa Margolles and Hermann Nitsch at the Box Company, Dallas, through February 17th, 2017.