Pablo Picasso, Woman Sitting in a Chair (Dora), April 7, 1938. Ink on paper, 25 5/8 x 19 3/4 in.

Pablo Picasso is an art historian’s dream. His appetite for artistic styles and radical reinterpretations of works by past artists with whom he identified makes him an encyclopedia, not just of Western art history, but also of the history of human civilization.

Picasso’s role, along with Georges Braque, in the development of Cubism is understood as his most enduring claim to art historical permanence. But Cubism is at most only half the story of Picasso’s fame and popularity in our own historical era. Picasso The Line, at the Menil Collection in Houston, is an exhibition of drawings, installed in chronological order, that span most of his career. The show functions as an outline of Picasso’s vision of the past and his insight into the future of art and human life.

For me, the most mysterious and exciting aspect of Picasso’s artistic evolution lies in his decision, once he had travelled to the fragmented edge of the known territory of visual art with Cubism, not to dig in and live there for the rest of his life, but to circle back and explore the more cohesive iconography of the ancient Greeks, Romans and his more immediate 19th-century predecessors. The Line allows us to understand that for Picasso past was indeed prologue.

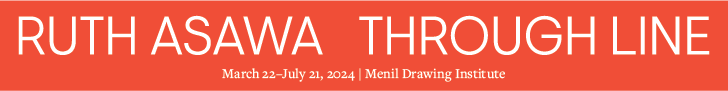

Pablo Picasso, Sketch of Andre Salmon, 1907. Charcoal on paper, 24 3/4 x— 18 3/4 in. 2016 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Both Cubism and Einstein’s Theory of Relativity came into existence at virtually the same moment and ushered in an era of radical subjectivity. Both Einstein’s theory and Picasso’s distorted pictures suggest that what is perceived in the world depends upon the viewer. Einstein gave a famous illustration in which a passenger on a moving train perceives two lightning strikes occurring at two different moments while an onlooker on a platform perceives them as striking simultaneously. Both perceptions are true but depend upon the viewer’s position in space and time.

Pablo Picasso, Violin on a Table (Violon sur une table), 1912. Watercolor, charcoal, and paper on paperboard, 24 1/2 × 18 1/4 in. (62.2 × 46.4 cm). The Menil Collection, Houston. © 2016 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Standing in front of a Cubist picture, the viewer becomes both the motionless figure on the platform and the passenger in the train whose perception is fragmented. Without moving, the viewer imagines himself dropping to his knees and looking at a table leg before he rises up to the ceiling to look down on the surface of the table, just before he veers to the left, catching a glimpse of a vase of flowers only to be jolted back to the right where he barely makes out the neck of a violin before he’s off again.

Picasso (and many others) understood very early that the 20th century would be one of dizzying movement, discovery and innovation. It would also be a century that visited unseen horrors and violence on human beings, often at the hands of those same whiplash technologies. Picasso seemed to understand that the human being was still basically primitive and had evolved over millions of years to adapt to an environment without man-made technology.

This tension between the human’s adaptation to a hunter-gatherer existence and its sudden immersion into a world of fighter planes and theories about black holes can be seen in a small portrait of Dora Maar in the exhibition. Maar seems trapped and distorted inside a horrible device that might be an electric chair or a cockpit in a spaceship being sucked toward an event horizon. The grisliness of many of Picasso’s Cubist portraits suggest to me that his vision of a Cubist future for human beings was not particularly sanguine.

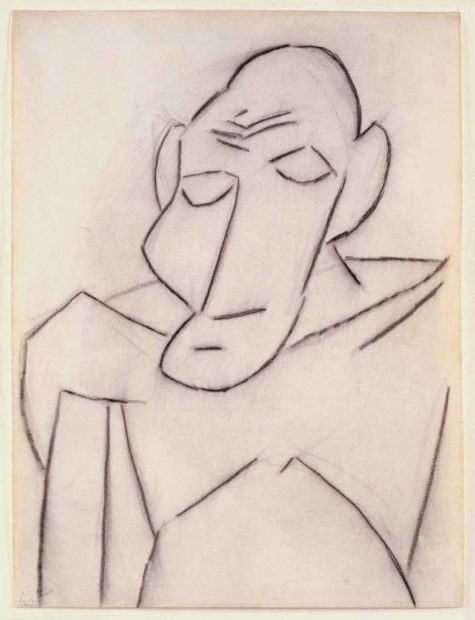

Pablo Picasso, Study for The Interview, winter 1901 – 1902. Graphite on paper, 18 1/8 x 12 3/8 in. 2016 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

I suspect that Picasso even shocked himself with his early Cubist innovations. He spent the rest of his career retracing the steps that had led to his Cubist work and the tear in the fabric of art history it had created. After Cubism (and the fame and wealth it brought him), Picasso began work on the paintings and drawings that comprise his Neoclassical period. These pictures are a fusion of Greek vase imagery, Roman frescos and late Medieval/early Renaissance painting. The single line that connects the forehead to the tip of the nose in much Picasso portraiture is derived from both the ancient Egyptian and Greek depictions of the human face in profile. The heavy, solid depictions of the figures seem drawn almost directly from Giotto and Masaccio.

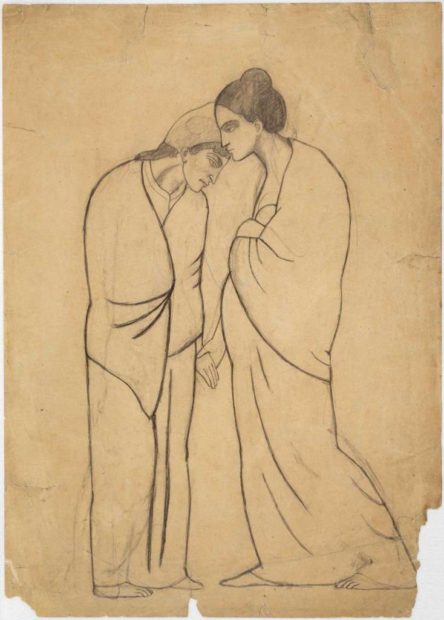

Pablo Picasso, Study for Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (Étude pour Les Demoiselles d’Avignon), May 1907. Charcoal on paper, 18 3/4 × 25 1/8 in. (47.6 × 63.7 cm). Kunstmuseum Basel, Kupferstichkabinett, inv. no. 1984.494, Gift of Douglas Cooper, Paris, 1984. © 2016 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Neoclassical period is also characterized by Picasso’s depiction of women as primarily sexual beings. The female form in much of the work on view (particularly the later works) seem to be drawn from the labia outward, with the face a necessary but secondary feature. The crude and funny sexual exploits in Roman graffiti and private-residence frescos are candidates for sources in many of these pictures. But more than that there seems to be an ancient preoccupation with fertility and reproduction.

In his work, if not in his life, Picasso understands women as symbols of fertility, sexual power, and carnal pleasure. While I think it’s silly to accuse Picasso of outright misogyny (he clearly loved women) it’s not inaccurate to observe that as a voraciously heterosexual male, he admired women more for their ability to reproduce and give pleasure than for their artistic integrity or business acumen.

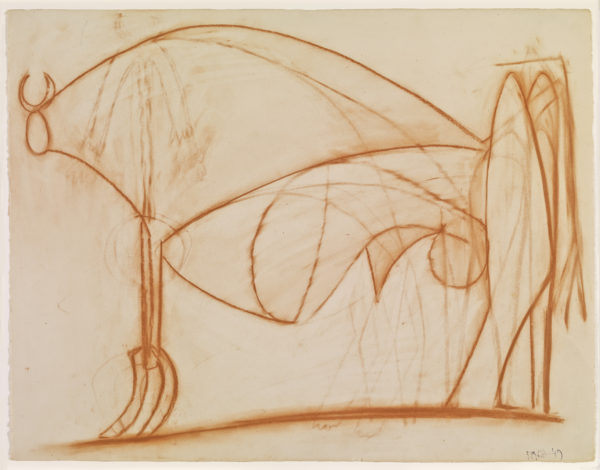

Pablo Picasso, The Bull (Le taureau), August 5, 1949. Red chalk on paper, 20 1/8 × 26 in. (51 × 66 cm). Private Collection. Courtesy Almine and Bernard Ruiz-Picasso Foundation for the Arts. © 2016 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: FABA

And this is the strangeness of Picasso. For all his rightfully earned praise as one of the fathers of Modern art, he appears to me as a uniquely Antiquarian kind of Modernist. His repeated depiction of bulls and cows stretch all the way back to primitive cave paintings while somehow managing to invoke a butcher’s poster illustrating cuts of meat. Matisse, his famous rival and friend, seems entirely Modern, almost frivolous, but Picasso maintains a connection to a darker, more distant human state of mind.

The connection between early agricultural civilization and the yawning uncertainty of our future is most visible to me in a small drawing tucked in a corner that depicts a man with a simple flute leading a bull by the horn. The title is Naked Man Taking a Bull to Slaughter. Dated 1902-3, it was made four or five years before Picasso would be swept up by and begin to steer the Modern upheaval leading to WWI.

I recently finished reading The World Until Yesterday in which Jared Diamond describes the differences between traditional hunter-gatherer formations and our own contemporary mega-societies. As I looked at the simple contour drawing I envisioned, at a stroke, the entire history of domesticated animal slaughter from the simple moment in the Picasso drawing to our present situation in which millions of animals suffer enormous pain for the mass production of meat while contributing to greenhouse gas emissions that along with other factors threaten human existence itself. Like Picasso, human society will need to look not only to the promise of contemporary technology and innovation, but to the practices and mistakes of the ancient past if we hope to grope our way toward a future worth living.

Through Jan. 8 at the Menil Collection, Houston