What does it mean to be a master of fine art? At a moment when tens of thousands of “masters of fine art” are being minted every year it’s a good time to reconsider the question. The work of a master must be autonomous. It must have reached a point in its development over time when its formal integrity can no longer be questioned. Queries beyond this point are either of meaning or preference, but not of coherence. Susie Rosmarin’s geometric, process-based paintings, on view now in a survey of her work at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, are masterful.

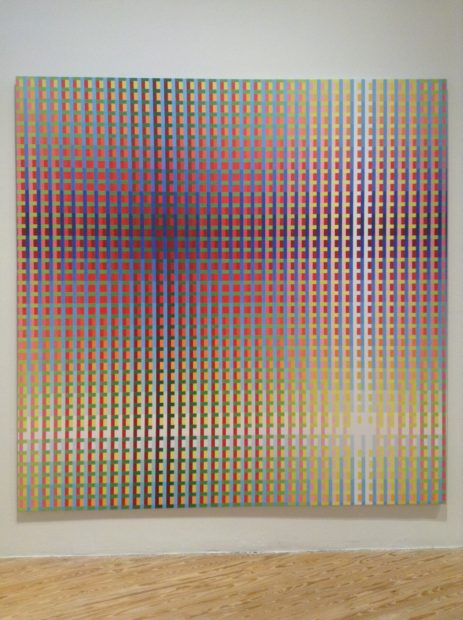

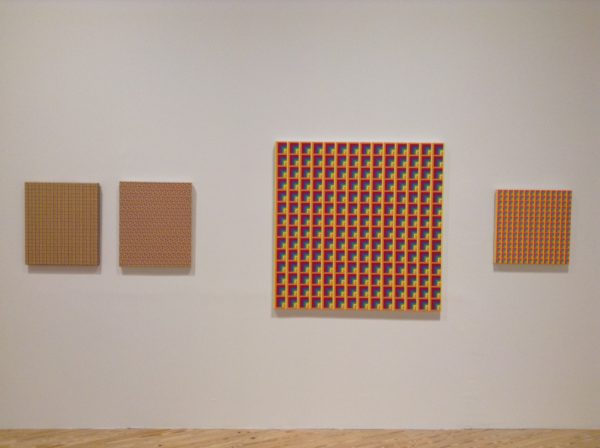

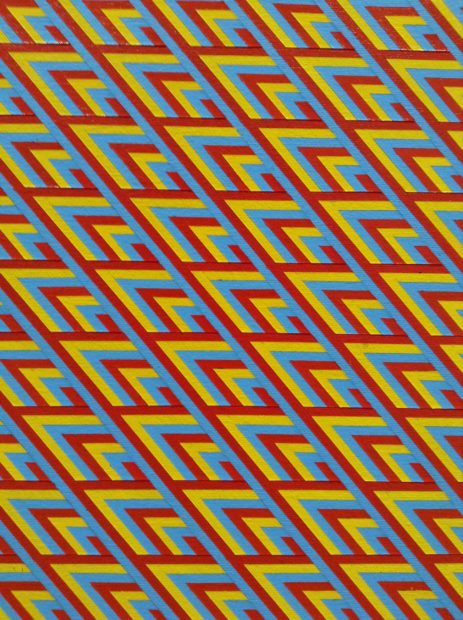

Rosmarin often uses mathematical formulae, algorithms and rigorous taping and masking techniques to generate the formal decisions that lead to the creation of her pictures. Rosmarin’s paintings are executed flawlessly. It would be pointless to try to find fault with her grasp of color theory or her proficiency in applying paint to canvas in a way that renders her hand as invisible as humanly possible this side of a machine. There is some connection to Sol Lewitt and to the larger tradition of Op Art painting here. But for me, there is something else—something darker in this work.

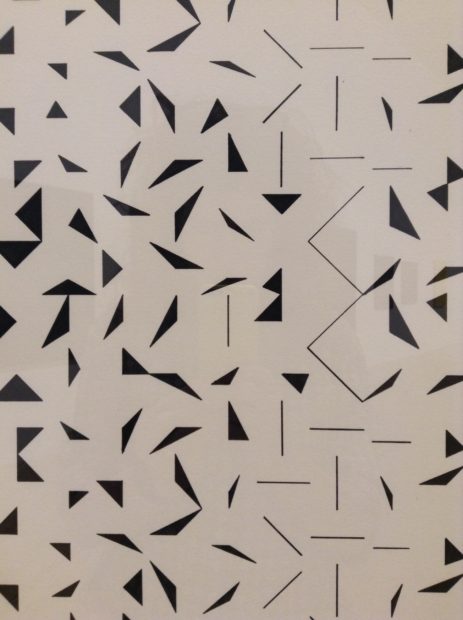

For an artist to master a process, they must overcome, time and time again, the conflicts built into that process. These conflicts—between what can be controlled and what cannot—are at the center of any artist’s practice. The task Rosmarin has set for herself is to be conscious, and make the viewer conscious, of the act of seeing. In a 2002 New York Times profile, Rosmarin said, “I’m interested in the experience of seeing. I’m interested in what we know through our sensory perceptions.” The conscious lack of control in those paintings that are put into motion through a formula and the unpredictable outcomes that can be expected when tape is pulled away from the edge of wet or dry paint are some of the formal conflicts over which Rosmarin successfully asserts her authority.

But in me Rosmarin finds a problematic viewer. My vision is profoundly diminished due to damage to my optic nerves in the wake of a surgery four years ago. My color perception and acuity are normal, but my peripheral vision is extremely constricted. So constricted that in order to fit even a small canvas into my field of vision, I must step back far enough that many of the paintings lose their richest optical effects. To see most of Rosmarin’s medium-sized paintings optimally, the viewer unconsciously places his or her body in a kind of middle distance from the wall, just far enough back to let the colors and lines fill their visual field but not so far back that the wall and the edge of the canvas stabilize them.

But when I stand in this visual sweet spot, my central area of preserved vision forces me always to be inside Rosmarin’s grids and dancing algorithmic lines. I move from section to section, largely untouched by the optical effects for which her paintings are known. I remember seeing her work before my vision loss and their electric vibrations were perceptually disorienting. They no longer have this effect on me. As I approach her work now, I’m inside the grid, exploring a detail, observing the color of a particular line as it crosses another, noting the raised edges where tape kept the wet paint contained.

Standing simultaneously inside Rosmarin’s paintings and outside of their optical illusions is what brought me to think of her work in the explicit terms of artistic mastery. I tell studio students that in order to understand a painting, they must look at it until the illusions, optical or narrative, fall away and it reveals itself for what it is: colored mud smeared on cloth. If they can see the mud and not the picture they can begin to understand how the thing was built. They can see how the mud was smeared.

Stripped of the pleasure of their illusions, Rosmarin’s paintings become an accretion of iron-fisted decisions. Control and dominance—over nature, over vision, over the viewer’s bodily movements, over herself—become the driving themes in her work. Also on view is one of Rosmarin’s notebooks in which page after page are covered in neatly handwritten numbers, sequences in the algorithms used to plan some of the paintings. In this light, the visual effects of her paintings seem to be almost a byproduct of her need to create an orderly universe.

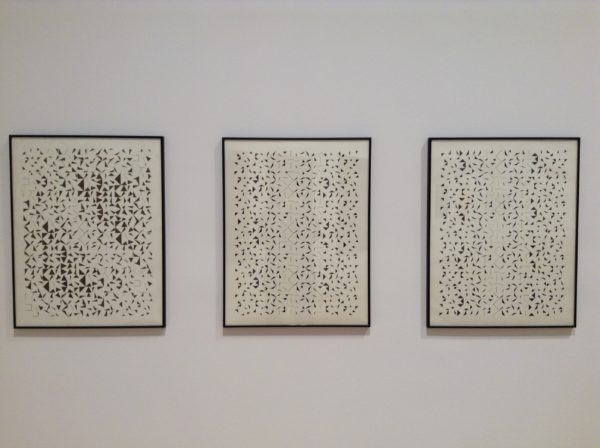

Rosmarin often makes small studies of her paintings, some of which are on view in this show, before making the larger works. She plans ahead, resolves potential roadblocks and surveys the terrain for unforeseen circumstances. Then, when everything that can be accounted for is ordered, she executes her plan, which, in a tyranny of visual stimulation, enlarges pupils and sends signals speeding along optic nerves to activate the visual cortex of her viewers. In this calculated process Susie Rosmarin masterfully orders her universe. Seeing and thinking about Rosmarin’s work has helped me cast my own studio process in sharply different terms.

At night, with the lights out, I am nearly blind. Light perception is at the heart of what we can and cannot see. When I get up from bed to go to the bathroom or refill my glass of water, the moonlight through the sheer curtains in my bedroom is not enough to enlarge my pupils. I put my hands out in front of me to protect my nose from the wall. I feel for the door handle. The process of making my drawings has become like this. I know almost nothing about how my pictures will look when I begin. Beginning in the dark, I drag my pencil along the paper searching for the next line, tilting my head, moving my eyes rapidly, trying to fill in the visual gaps. I think Rosmarin would be interested in this.

“Susie Rosmarin: Lines and Grids: The Lost Decade and Beyond,” organized by Senior Curator Valerie Cassel Oliver, is on view at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston through Nov. 27.

2 comments

At first I thought this was going to be an MFA bashing article. But then I realized that it is a thoughtful, sensitive and deliberate essay examining the work of Susan Rosmarin. Thank you for the great work!!

Thank you, Michael, for sharing your experience of Susie’s works. You have invited us to see her intent and process in a different and very personal way.