Matthew Zefeldt’s work feels right at home in Circuit 12’s newish location in the Design District, in Dallas. His show is bright and slick and ambitiously current. It consists of around 15 medium-sized acrylic paintings, a large wall painting covering the back of the gallery, and a floor piece made of vinyl tiles whose different tones construct a pixelated reflection of the wall piece, stretched to fit the length and width of the gallery floor. These two site-specific accompaniments to the paintings are large-scale riffs on Zefeldt’s methodology, which is to mimic digitally manipulated images by painstakingly gridding off and manually executing their cool surfaces.

I’d seen his work before in a group show, and was wary, as I tend to be, of the sugary digital aesthetic, the rainbow color fades, and most of all, the painted pixels. But something about the lushness and craft of the paintings kept me looking. This solo outing, titled Marble Head From a Herm, convinces me of the commitment and clarity of Zefeldt’s vision by revealing the limitations imposed on his practice. There’s a surprisingly meditative quality to the work. Straightforward, meticulous depictions of the same marble head provide the refrain. Both the variety and rigidity in the works grow from a calibration of process.

Spaced

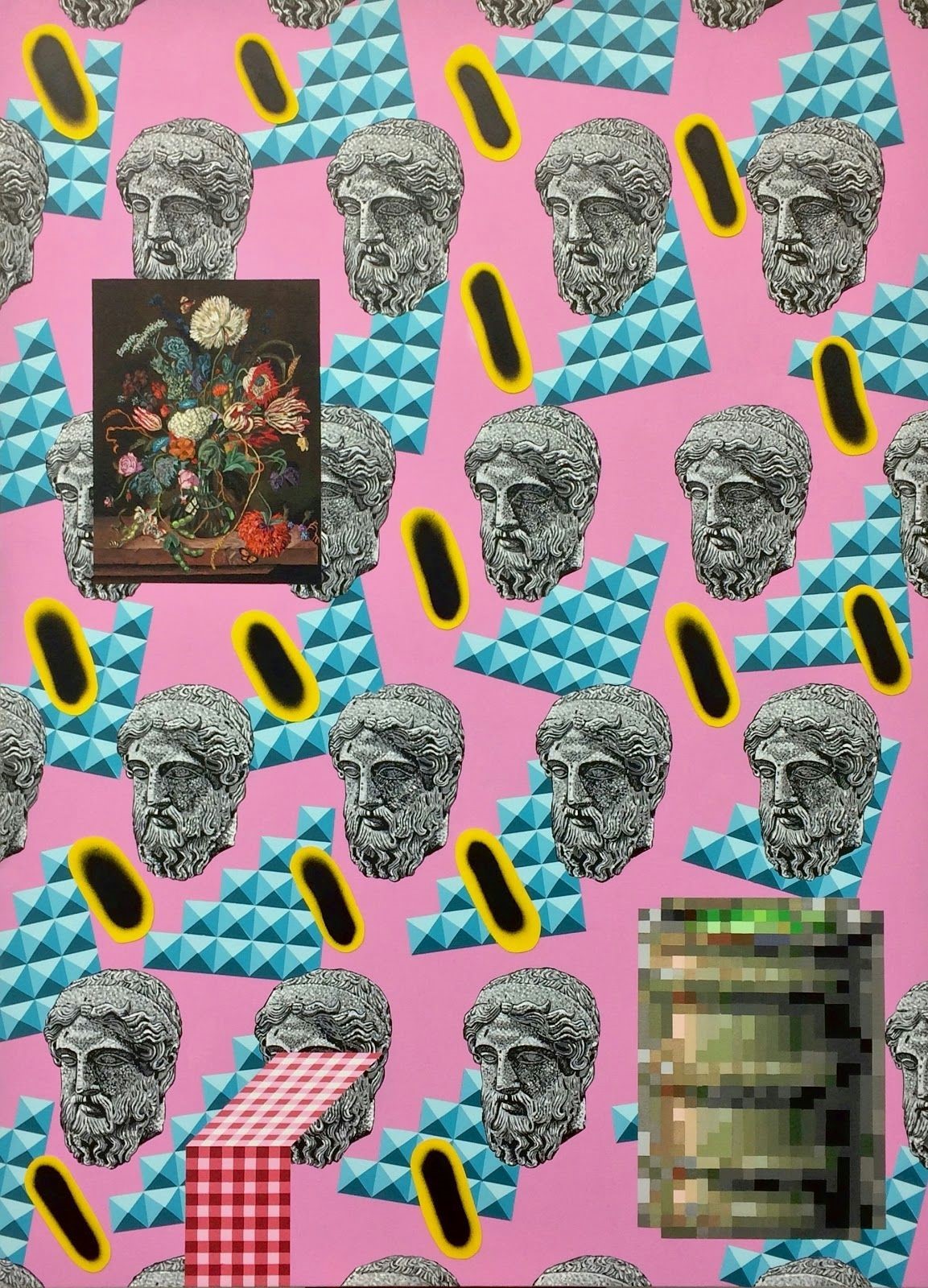

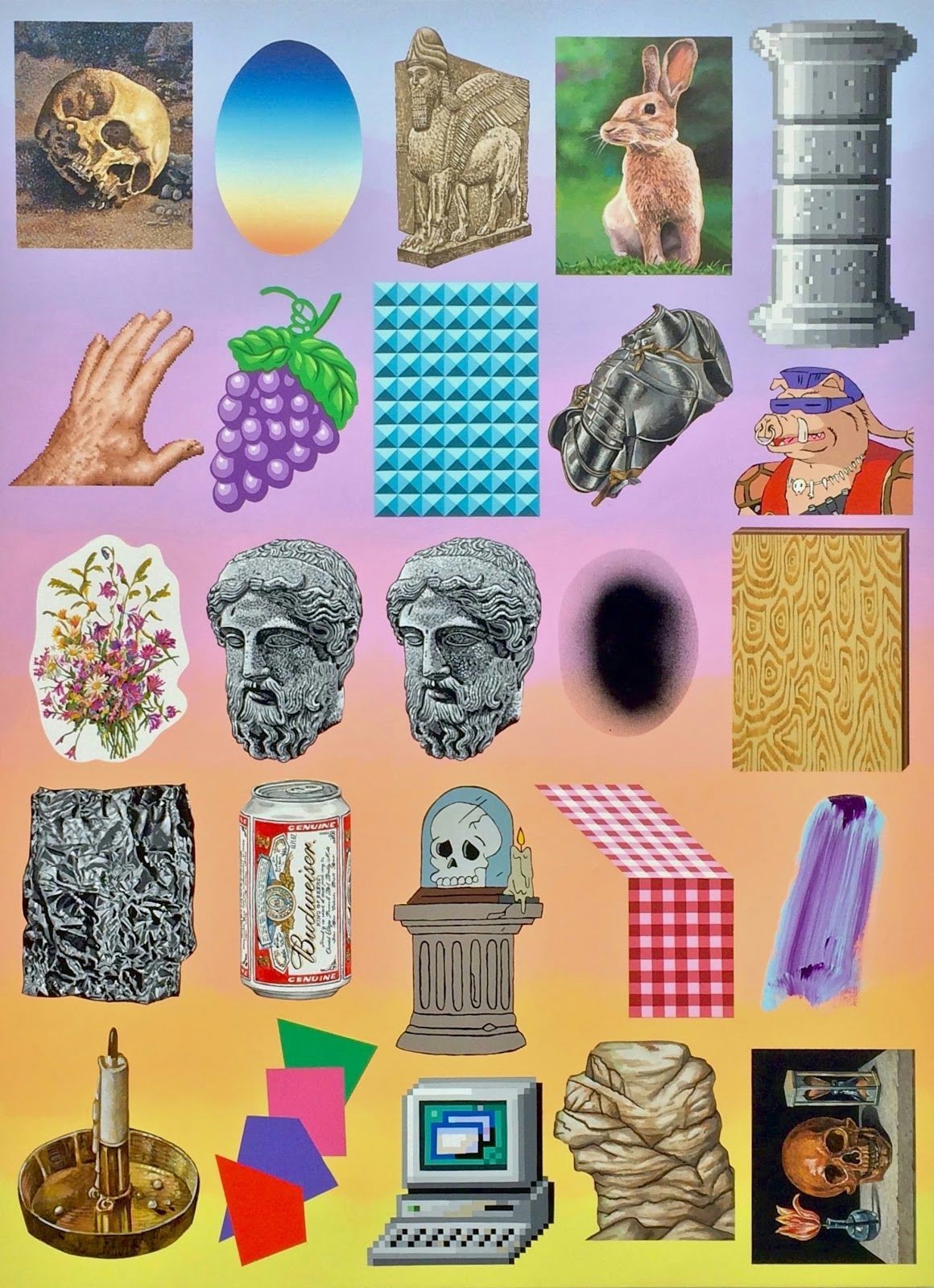

The head in question, supposedly a Roman copy of a Greek bust of Hermes, seems to be an arbitrarily chosen motif—used for its art-historical patina as a base flavor for quirky combinations and arrangements. The head image is painted in the same ¾ pose over and over again: in off-kilter grids, overlapping themselves, repeated like wallpaper, even photo-melded with a rabbit. There are around 200 of them in attendance here, nearly identical but genuinely imperfect. They share space with cans of Mountain Dew, early Nintendo characters, and clip art, among other things.

Two Things at the Same Time

Somewhere in this gesture is the need to gather ancient and modern representations together into a single media, translating all of their disparate styles and finishes into an equally stylized compendium of icons. Zefeldt dredges up unlikely examples of visual languages, culled from fine art, advertising, cartoon animation, video games and sculpture. Some of these objects have been routed through stone, film, paint, imagination, computer software, and back into painting. There is so much distance between the objects and their referents. Zefeldt paints that distance into punchlines.

Some Sum

It’s hard to appreciate how much visual media models not only our perception of space, but also what to make of it. How representations are “touched,” “handled” and consumed provide powerful material metaphors that frame and script our reality. Zefeldt’s work plays with the visual tools of our time, themselves explicit representations of real-world tasks. The world really is flat, after all—the “world” being our collective understanding of our universe. It exists as retinal impressions, filed away with visceral associations and ordered into narrative logic. If narrative is what holds our world together through time, pictorial perception holds things together in space. And as we’ve found ways to build these impressions back out into the world, we’ve effectively created an external “retina” on cave walls, chapel ceilings, scraps of paper, and Instagram. But the making of these external images traditionally involves a physical understanding of their substance through process, an involvement with the witchcraft of making something out of something else. These facts are getting easier and easier to conceal. The immersive speed of technology has caught up to us. Yes, we are going places. But what do we want to bring along?

Overlapping Heads From a Herm

There are theories that locate cognition throughout all of the body, rather than merely in the brain; thinking may happen in our fingers, our tongue, and our muscles. Likewise, our first idea of space is formed through the exploratory movement of our limbs as infants. What I’m working towards here is that there’s an important phenomenological tether to pre-picture matter that highly processed images want to glide past. And this is what painters are continually ravished by—playing and replaying that simple illusionistic trick that grounds the virtual in the material. It seems that some modern fetish for invisible technology (while connecting our will to the tasks we need to complete) pulls us like a magnetic pole away from our bodies as the grounding force of our consciousness in the material world.

Zefeldt may be trying to reclaim the products of our pictorial language by digesting them in his process, funneling them again through body and mind. His effort won’t be lost if we can slow ourselves down enough to see what he’s doing.

Matthew Zefeldt, through July 30 at Circuit 12, Dallas.

(Images courtesy of Circuit 12 and the artist.)