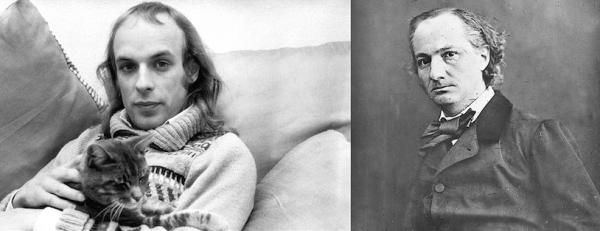

Eno/Baudelaire

I’ve never been a musical person. As a child and a teenager I was insecure in my appreciation of music. My earliest experience with music was listening to the congregation in my family’s Pentecostal church singing hymns. It was a coercive, manipulative church so there was little joy in the singing. But it was there where I realized that my dad could play the guitar. He and his friend Tom would go to the front of the church every now and then and play as a duet. Cynical as I was about the church, I was intrigued by and a little envious of my dad’s ability to play the guitar.

I asked him if he would teach me to play. He said he would and we went to the guitar store where he bought a pitch pipe and a book of guitar exercises. He tuned his acoustic guitar using the pitch pipe, gave me a few pointers and told me to come see him after I had practiced the lessons in the book for a few weeks.

I was disappointed and blamed my thwarted rock star career on what I thought was his lack of interest. It wasn’t until after he died that I understood that I hadn’t been interested in playing the guitar. I had just wanted to hang out with the old man. He took me at my word that I wanted to learn to play. But he also knew, because I had never shown a real interest in music, that I wasn’t a guitar player. I never practiced of course. I had drawings to make. The lesson book disappeared over the years but the pitch pipe followed me all the way to grad school. It’s lost now. Sometimes losing something puts a punctuation mark on a story that’s been unfolding for a lifetime.

Music has often been a central but underestimated part of my life. As soon as I got a Discman and a set of cheap headphones, I checked out of the sounds of the college campus, the street, and the highway. My tastes weren’t sophisticated. But they didn’t need to be. Nirvana and Jane’s Addiction spoke to that part of me and a million other angry suburb kids who knew that the America we inherited was a battered ideal. The popular rock of the early ’90s helped me shake off the fear that religion inculcates in children for life. It was loud, angry music for a loud angry escape. (Fear of damnation after death doesn’t go quietly.) I was one of millions of kids for whom that music performed the same function. God bless it for that.

I didn’t understand the significance of classical Western music until I read about Nietszche’s intellectual romance with and eventual rejection of Richard Wagner. Nietzsche and Wagner looked back through history to locate their ideals of culture in the the ancient Greeks. In his later years Wagner degenerated into a racist whose musical aspiration toward a glorious past didn’t leave much room for non-Germanic people and especially not for Jews. Nietzsche wasn’t anti-semitic, but was guilty of sharing Wagner’s desire to drag the past into the present by force if necessary.

The Frankfurt Marxist Theodor Adorno infamously wrote six essays over thirty years denouncing jazz music as lacking formal integrity. Adorno’s conception of musical formalism was so rigid it blinded him to the obvious Modernist brilliance of jazz. His blindness was the result of an intellectual inflexibility that prevented him from realizing that classical music had lost the revolutionary potential it held for Nietzsche. His sharp critiques of American culture prevented him from seeing that revolutionary potential could live inside capitalist entertainment.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve realized that all forms of music at their best share the ability to transform consciousness. A few years ago I came across the composer Harold Budd who led me to a renewed interest in Brian Eno. At the same time I finally delved all the way into the work of the 19th-century poet Charles Baudelaire. Both artists have floated in and out of my periphery but finally came together forcefully enough to change my work. The opium-den grip of Baudelaire and Brian Eno is a pretty seductive hold. My last exhibition and more than a few articles on these pages dipped deeper into surrealism than I had ever allowed myself to dive before. (Watching a documentary on H.R. Giger recently, I realized that some artists never swim back to the top.)

Moving in and out of different forms of music over the years has crystallized the profound effect that art can have on how I see the world. Baudelaire and Eno actually changed my understanding of reality. With them, I looked at the world through a very long lens. I felt a sense of loss, as if the primeval past evoked in both Baudelaire and Eno contained the answers to the mysteries of the present.

This is a dangerous position to occupy. The human struggles of the past are the same struggles we face in the present. In each epoch, people battle against their own nature. And that nature has not changed. It will never change. Art doesn’t allow us to transform our nature, eliminate our tribalism or bring us closer to some abstract ideal of what we should be. But it does help us shift our perspective and allow more stories to come into view.

A buddy of mine has been trying to pull me into his World of Metal over the last year. I’ve resisted because in my old age loud noises make me nervous. But you never know. If I do and if it sticks you’ll see it here.

\,,/(*_*)\,,/