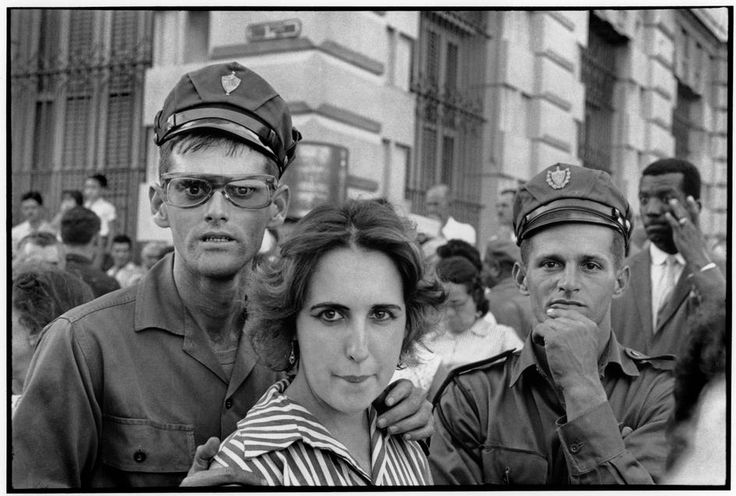

Havana, Cuba, 1963

One of the most annoying habits in politics and art is the tendency to oversimplify history. Politicians and artists, on the left and the right, often force historical figures to represent entire institutions and histories instead of human beings in a time and place. It’s easy to do and sometimes the reduction works. But more often than not, these simplifications result in bad history and dangerous ideology. Human beings and the messy things they do are complicated. Any history that will be of use to the cause of freedom and liberation will necessarily be as nuanced as human beings are complex.

Complicated and nuanced history is exactly what you’ll find on view at the Menil in Life is Once, Forever:Henri Cartier-Bresson Photographs, an exhibition of black and white photographs by the famous humanist photographer and Magnum photo agency co-founder Henri Cartier-Bresson. Cartier-Bresson was notoriously casual about printing his photographs. In fact, he didn’t print his own work. It was sent out for processing. In interviews he said that processing took up valuable time that could be spent taking pictures of the world as it moved around him and he through it. Cartier-Bresson and other street photographers who came of age after World War II took it as their mission not only to record humanity as it tried to rebuild itself after half a century of war, but also to editorialize, to present a particular vision of what humanity was and what it might yet become.

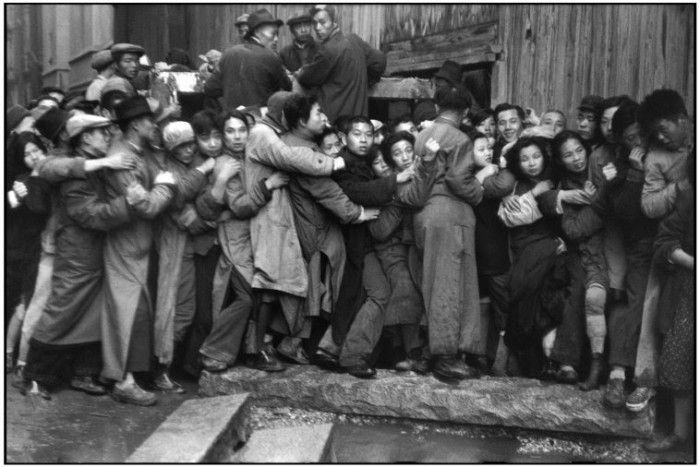

Shanghai, 1949

For Cartier-Bresson, man is never free of his place and time. Every photograph in the exhibition is simply titled by location and date. Cartier-Bresson’s formal law is geometry. His subjects are pictured within the geometric structure of the cities and industries they have constructed. Though he might deny it (his interviews are entirely too cagey, spiritual and esoteric for my taste) Cartier-Bresson is a historical materialist. He shows us again and again, through the bombed-out shells of war-battered places, the crumbling architecture of ancient cities and gleaming monuments to the modern world, that the bulk of human life is determined by its material production. But he rejects an oversimplified version of the argument that art, culture and the human freedom that comes with them are solely determined by the economic base of a society. Cartier-Bresson’s human subjects are full of agency in spite of their positions in historical moments over which they may have little control.

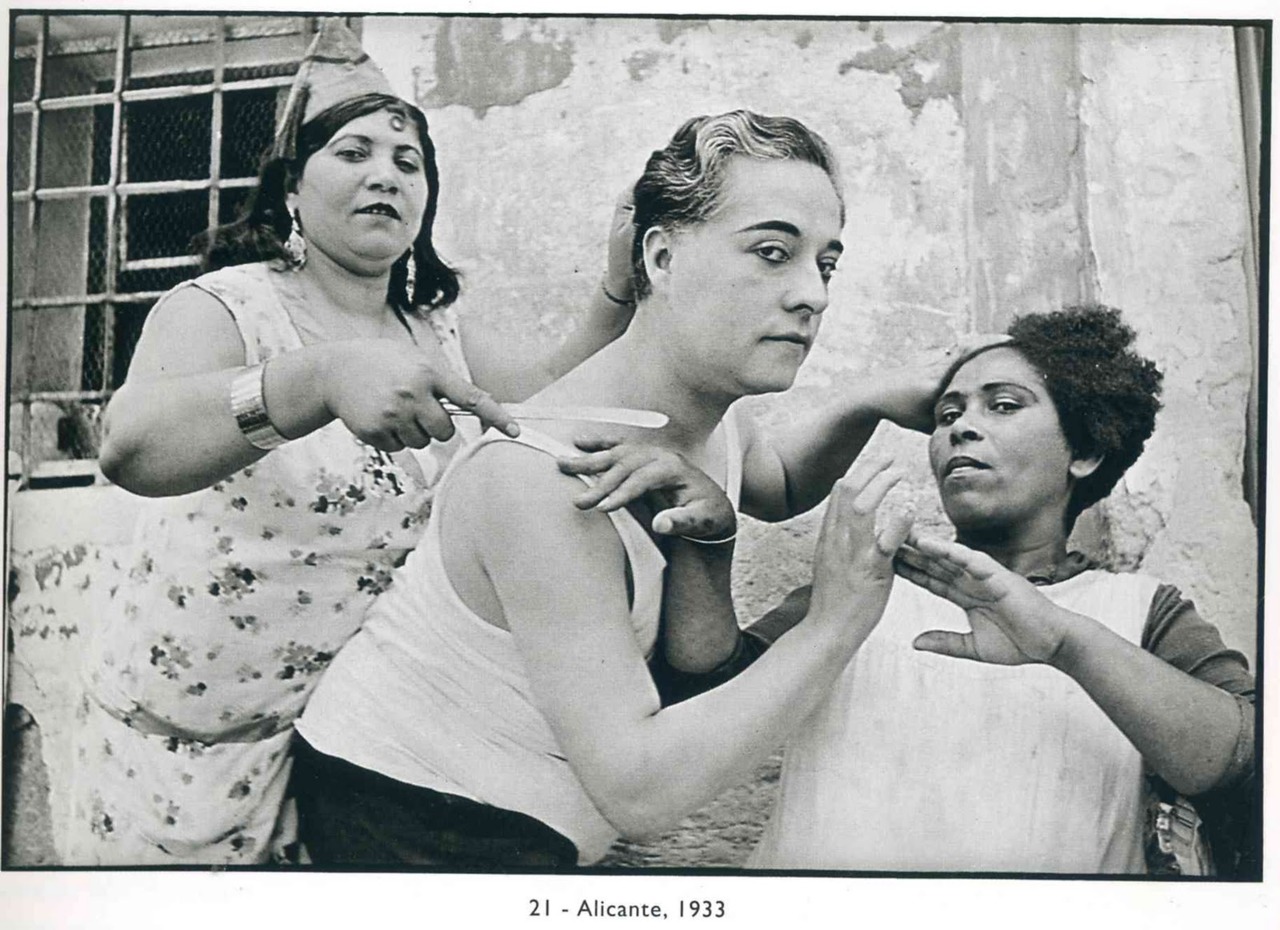

Alicante, 1933

In Shanghai, 1949 a man inexplicably smiles while standing in a crushing line as Mao’s Communist army takes the city, forcing the Republic of China Nationalists to evacuate two million people and much of the Chinese gold reserve to the island of Taiwan, which remained under martial law until the late 1980s. In another picture, three sexually ambiguous and very tough looking young people primp and comb each other’s hair in the ancient Spanish city of Alicante, originally settled in 324 BCE. Their uncompromising glances were captured just three years before Francisco Franco would violently suppress a leftist uprising that resulted in real political gains for parties who claimed to represent workers, students and intellectuals. Many of the cultural tensions between rich and poor, conservative and radical that flavor our current American political landscape boiled over into the Spanish Civil War in 1936. Five years after Cartier-Bresson captured these this image, George Orwell would publish Homage to Catalonia, an account of his participation against Franco’s Nationalists. I see the same hard-edged human empathy in Alicante, 1933 that I value in the Weimar-era German painters like Max Beckmann and George Grosz.

Cartier-Bresson’s subjects are often oppressed by the same weight of geopolitical realpolitik and theocratic extremism that continues to impact every human being on the planet today. But he does not often choose to depict people in their weakest, most broken state, and this choice comes with the risk of being accused of flinching from reality, of turning away from a dark truth about human nature that must be stared in the face in order to legislate greater freedom and civil security. The truth is that we need both conceptions of human nature—the empathetic and the brutal—to understand ourselves. I don’t believe Cartier-Bresson flinches but if he sometimes idealizes more than I like, I am nonetheless sympathetic. I still believe that there is some truth in the idea that the images we make of ourselves have an influence on what we become.

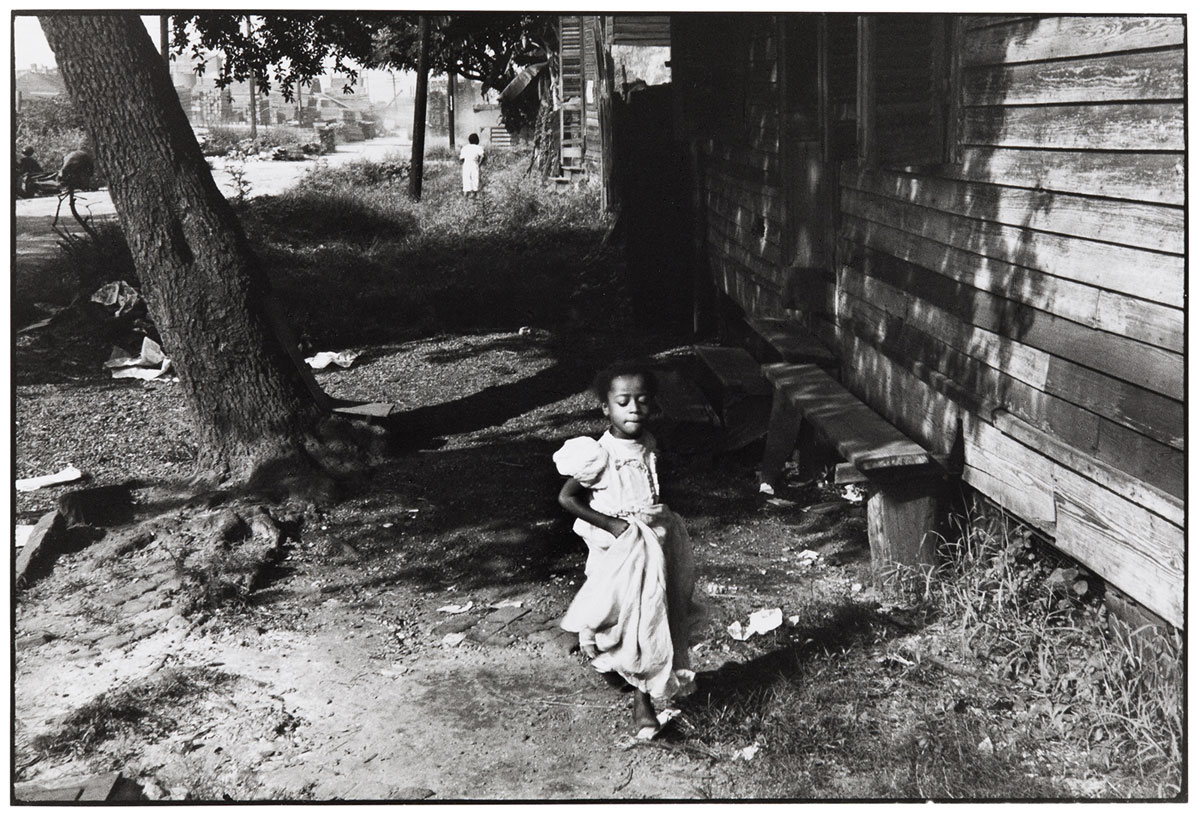

Louisiana, 1947

In Louisiana, 1947, a determined little girl holding the pleats of her long skirt is captured mid-stride. Cartier-Bresson caught her in his frame during the crucial years leading up to the historical moment in which black anti-apartheid resistance in the United States culminated in the mass liberation movement that changed the landscape of America in great and terrible ways. As I looked at the photograph I imagined the little girl walking out of the shot, down the street and out of the dilapidated trash-strewn neighborhood in the segregated South and into a life of meaning and reward.

But I don’t quite believe it. The fight goes on. The struggle continues. It’s complicated.

Through July 24 at the Menil Collection, Houston.

1 comment

What a great piece you wrote. Thank you for the interesting viewpoint — and wonderful insight.