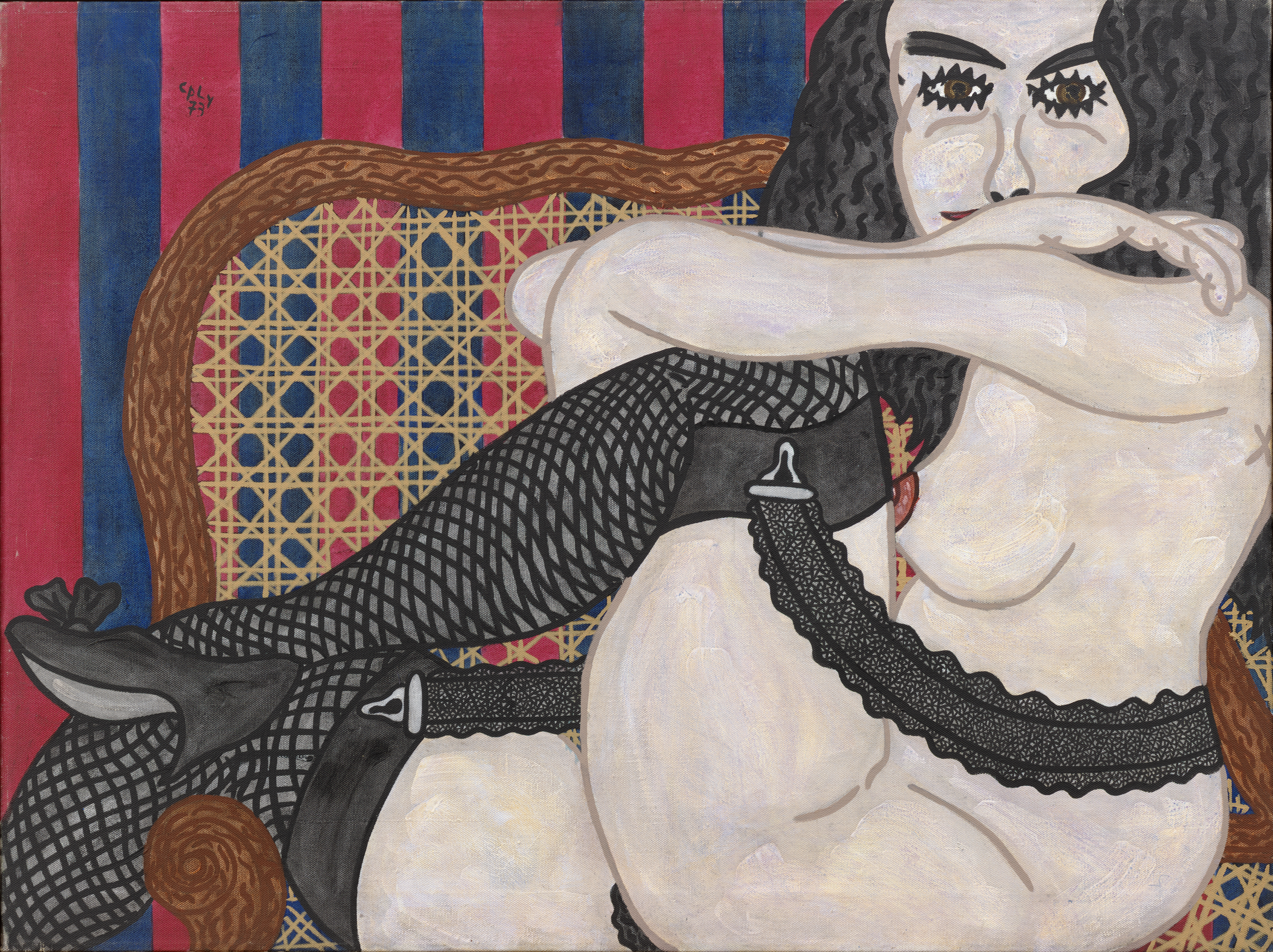

William Copley, Rain, 1973

We need to talk about William. In order to find our way into William Copley: The World According to CPLY, an exhibition of paintings at the Menil Collection curated by Toby Kamps, it’s important to separate Copley the mid-century art-world insider, collector and art philanthropist from the painter known as CPLY.

Copley’s historical significance rests comfortably in the fact that he befriended and helped to further the international legacy of French Surrealism by mounting exhibitions for many of its grand old men including Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp and René Magritte on the West Coast. Along with his then-wife, Copley also established the William and Noma Copley Foundation which awarded grants to artists as diverse as Richard Artschwager and Carolee Schneemann.

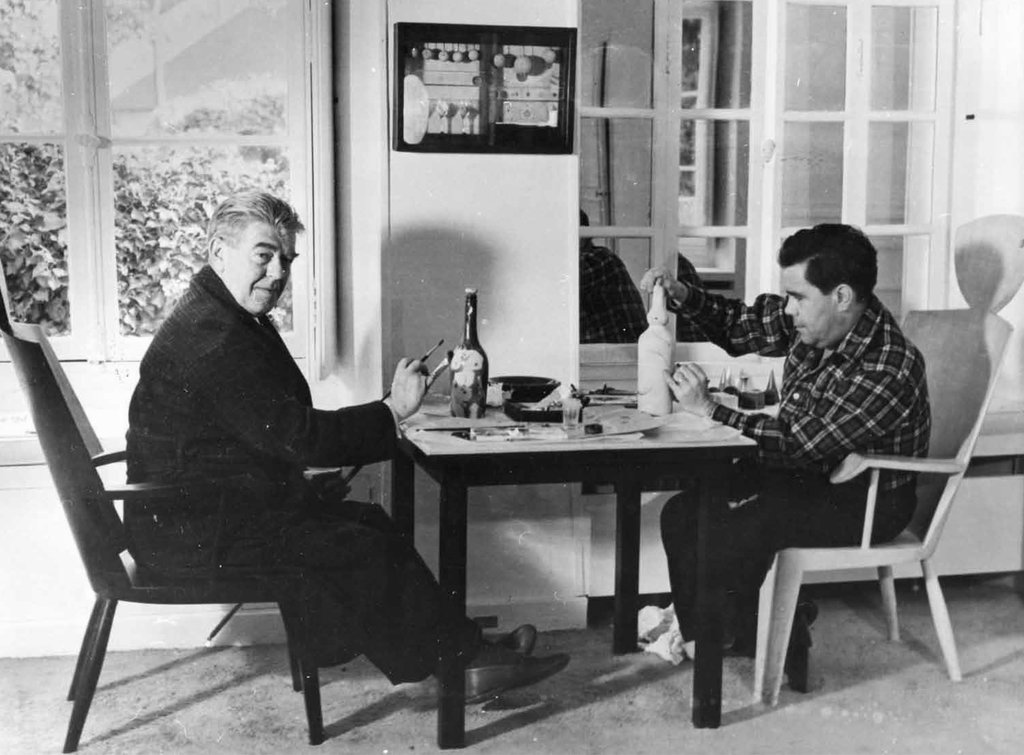

Dominique de Menil with William Copley, Institute of the Arts at Rice University, 1979

It makes institutional sense that Copley’s paintings and some of his collection currently takes up so much real estate in the Menil Collection. He amassed one of the largest collections of Surrealist art and several works in the Menil were acquired from him. In 1979 his collection was auctioned for $6.7 million, then a record for a single-owner collection in the United States. Kamps’ show isn’t the first time the Menil family name has hosted Copley’s actual paintings. Also in 1979, under the direction of Dominique de Menil, the Institute of the Arts at Rice University hosted an exhibition of Copley’s paintings drawn from sixteen Houston collectors, including the de Menils.

René Magritte and William Copley painting in Copley’s house, Longpont-sur-Orge, 1959

But Copley’s résumé as an art patron must be set aside when discussing his work. The undeniable truth is that Copley’s paintings, in spite of their humor and limited formal charms, are not very good. If that seems ungenerous we can trace Copley’s pictures to the well-established tradition of exceptional outsider art made by insiders.

Henri Rousseau, who claimed “nature was his only teacher,” exhibited regularly at the Salon Des Independents and received a favorable review from the artist Félix Vallotton. In Copley’s own era, the troubled artist Ray Johnson, often viewed through an outsider lens, attended Black Mountain College and moved in the neo-Dada circles of Merce Cunnigham, John Cage and Robert Rauschenberg. Johnson’s suicide at 67 is often disingenuously interpreted as his last performance, creating a narrative that combines avant-garde radicality with outsider madness.

Outsider art (whatever it actually means) has become more popular over my lifetime, including among artists. In a cultural establishment so blatantly corrupt, young painters look to naïve art as one of the last refuges of authenticity. But interesting outsider art is as rare as interesting insider art. A very good painter friend of mine boiled Copley down in a work of text-message criticism: “a rich guy with a hobby.” I’m inclined to be more generous. Based on the paintings in The World According to CPLY, I’m willing to believe that Copley was really trying to get something out of his mind and onto his canvases.

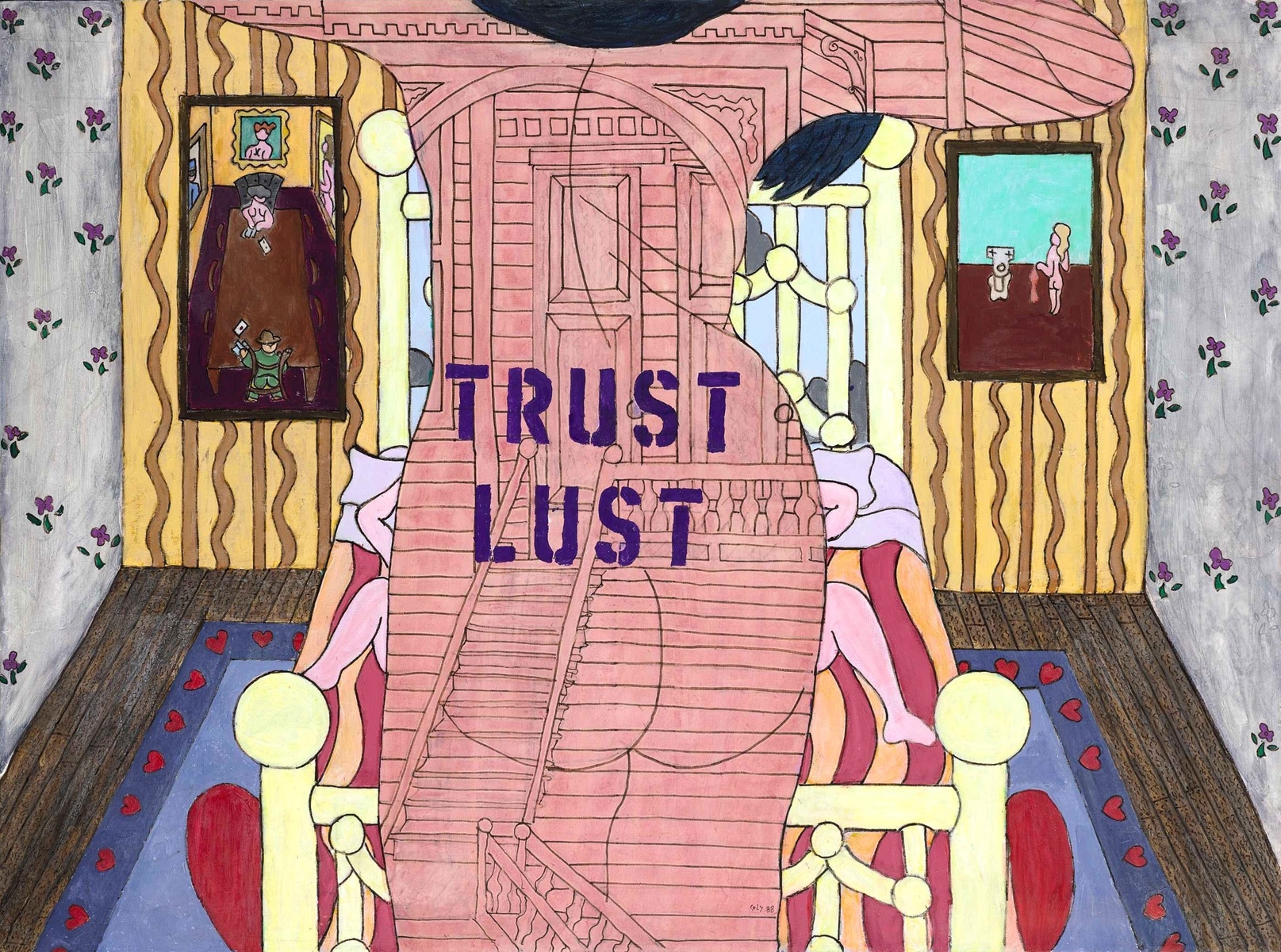

Copley, Trust Lust

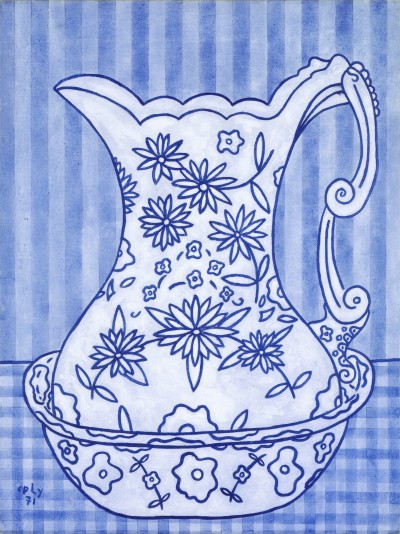

William spent the first two years of his life in a Dickensian foundling house, was adopted by a Gilded Age-era robber-baron politician, suffered six failed marriages, and if my years of self-therapy haven’t failed me, was afflicted with a simultaneously manic and repressed sexuality. Copley’s own description of his central theme of tits and ass as “the battle of the sexes” doesn’t do justice to his obsessive preoccupation with whores. Copley even describes his Nouns series—still life pictures painted from images in mail order ads—as possessing “hidden pornography” claiming “it’s easy to hide pornography in objects.”

William Copley in Paris

None of this disqualifies CPLY from being a good artist. In fact, it provides him with all the ammunition he needs to be a great artist. Well, not all the ammunition. Sincerity, authenticity or mental illness are never enough to create good works of art. For an artist in command of his medium, to reject mastery and make crude work is a powerful political decision. The trouble with real artists is that whatever their intentions, the material and ideas they choose to use are always transformed. Material transformation allows paint, charcoal or a found object not only to represent, but to embody an idea. Copley is not knowingly subverting painterly form. In every picture I found myself envisioning a dozen different formal decisions he might have made to elevate his images into truly evocative paintings while losing none of their anarchic charm.

Copley, En Garde, 1967

Copley’s beloved Surrealists were among the first artists to reject, on political grounds, the idea that art making required skill or innate talent. The traditional European ethos had led to millions of dead men in the trenches of the Western Front. So with admirable punk-rock insolence they declared that art would be toilets and pipe jokes from now on.

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917, reproduction 1964, Tate Modern

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, Pieta, St. Peter’s Basilica, 1498–1499

But the Surrealists were an academic bunch. Nude Descending a Staircase is a sharp example of just-barely-too-late Cubism. Magritte mocked the prototypical Modern art fascist Jacques-Louis David in a style nearly as accomplished as the academic master’s own with his joke painting Madame Récamier by David. The often-misunderstood trick of Surrealism is that mastery of form in art was never abandoned. This is the success of Duchamp’s art coup; the urinal, the wine rack and the bicycle wheel remain strong forms. In its title, Fountain evokes the Renaissance tradition of grand public art and its shape mimics the contour of Michelangelo’s Pieta. Duchamp may be taking a piss but he’s doing it with razor-sharp wit.

Copley, Pitcher and Wash Basin, 1971

If we reject the idea—and I think we should—that William Copley’s paintings are hanging in one of the most prestigious museums in the world simply because he was a rich guy with a connection, we have to ask the hard question: why are they there? Perhaps the greatest desire in radical art is to one day arrive at a historical moment when everyone is an artist. The internet and social media have so fundamentally “democratized” (or degraded) the idea of the artist that any activity can be understood as art. This has allowed curators to create revisionist histories in which any artwork can be given artistic significance which it may or may not possess. The only prerequisite for the creation of art in the 21st century is an idea or an emotion. This is the profound legacy of Surrealism and Dada, aided as revolutions always are, by new technology.

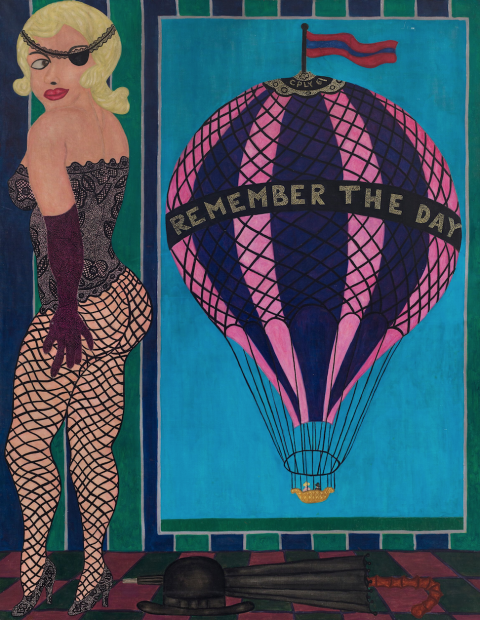

Copley, Remember the Day

I tell my art history students to think carefully about the concept of the avant-garde because art history does not move along a linear timeline. Forms move, change, and circle back but always revolve around the relationship of an individual human being with his society. In The Story of Art, E. H. Gombrich writes “the Egyptians had largely drawn what they knew to exist, the Greeks what they saw; in the Middle Ages the artists also learned to express in his pictures what he felt.” Copley painted what he felt but his medium consistently gets the best of him and gets in our way.

Through July 24 at the Menil Collection, Houston.

5 comments

98% of the best art in America in the 20th century was made by artists who were rich.

Dear Dave Hickey,

Thank you so much for your courage in sharing this very valid point!

Rich artists, like rich members of royalty, are the products of superior breeding by the grace of God. It would be blasphemous to deny them their God-given authority.

However, I think it is important for us to remember that, with privilege, comes great responsibility. These men not only had to PRODUCE 98% of the good work made in the 20th century, they also held the daunting responsibility of creating the templates of style and ideology for forward generations of academic artists. Not only do these men deserve our praise and admiration, but I think a degree of deferential sympathy is called for.

Dear Dave,

I know.

I’m not responsible for the click-bait.

M

I enjoyed the article and found it very interesting. Does the art world (“real artists”) then start standing in the way of those artists with the means to take the limelight, yet don’t possess the technical ability to accomplish what the sincerely feel? The art world may have been democratized but it has evolved into a plutocracy. In my opinion, it increasingly marginalizes the groups of artists who don’t possess the pedigree acceptable to the “gatekeepers”, and those artists who struggle to fraternize with the established art institutions. I don’t get the sense that the merit of artwork is the prevailing factor when choosing which artists to elevate to the stage. I love what Michael said about authenticity and sincerity. To me sincerity is the most powerful weapon to an artist, but it doesn’t hit as hard or as broad as irony and cynicism, which is unfortunate.

When I first stumbled upon Copley’s painting of the Soviet and American babes wrestling each other, I knew he was sex crazed “genius” (whatever the hell that means?) This show is one of the most memorable out of the hundreds of shows I’ve seen in the last several years. I see way too much art. I’m a vulgar person. I was smiling and laughing throughout the whole damn show. I was entertained. I guess that is verboten in a museum these days.