To me and a lot of other art people in North Texas, a new Celia Eberle show is something to look out for. She’s still obscure, in a sense, compared to the shiny young hustling artists on the scene or the veterans who we’ve developed certain expectations about. She lives about an hour south of Dallas, near Ennis, on a windswept chunk of land that hosts her house and studio, and while there are some other artists living out that way, her isolation is becoming inextricable from her image. It fits her and her work (which can come off as almost deceptively folksy) but it also keeps her at an odd distance from the hearts and minds of this region’s art lovers, and increasingly this disturbs me.

Eberle has a show up at Cris Worley’s gallery right now (her second solo show there), and it’s good—some of the work is exceptional, which is no surprise—and when I walked into the opening I felt a familiar rush of being wowed by what she’s made and despairing that it’s not destined for a museum show. She’s a longtime critical favorite who’s had to jump from gallery to gallery over her career, and her cultish fan base is a discriminating hodgepodge of regional curators, mid-tier regional collectors, and—tellingly—other good artists. (Last year she also was awarded a grant from the Joan Mitchell Foundation.)

Her work is complicated and weird, and its unexpected poetry demands a kind of viewer engagement that might scare away those looking for easy gimmicks. This means that her work is built to last, and a lot of the pieces she made ten or more years ago still resonate fully, and even feel a bit creepy in their prescience. Eberle, out there on her scrubby, chigger-laden acrage, knows which why the wind blows. She’s like a seer or a prophet, but I think the best artists are.

She had a quasi-retrospective at the Art Museum of Southeast Texas in Beaumont last year, but it didn’t travel and there’s no indication that she’s up for a show at any of the bigger museums or non-profits here in North Texas. The trick to unlocking Eberle’s appeal would depend on masterful presentation of the work. Because she makes so many different types of things in both two and three dimensions, she needs a very sharp curator to make sense of it for a wider public, but doesn’t every artist deserve this? Unlike Eberle, a majority of professional artists find their niche and stick with it, which eases a curator’s job considerably. In terms of guiding philosophy, Eberle has a solid, centered through-line, but she changes her work (sometimes drastically) for every show. More on that in a minute. In Beaumont, lacking any real input from the organizers, Eberle’s instinct was to pile years of her work into a monolithic, mountainous snake down the center of the gallery. It wasn’t unlike Maurizio Cattelan’s solution to his Guggenheim retrospective, and doubtless for the same practical reason. It was a clever and apropos near-narrative approach for the extremely varied forms her art takes.

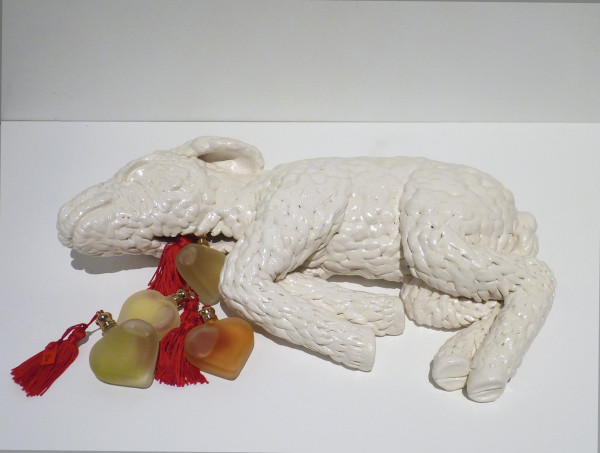

It boils down to this: Eberle is a conceptual artist. She starts with an idea and then teaches herself (from scratch) how to produce the things that communicate that idea. A lot of artists think they’re doing this when they’re not. Most artists know their skill set, and all their ideas, or “ideas,” fall safely within the limits of that skill. Like Cattelan, Eberle recognizes no such limits. The whole world of possible materials is available to her and is in service to her idea, and she masters whatever she needs to. She carves, sews, stacks, gathers, glazes and fires. She paints, renders, borrows, steals, and collects. And the result is that all of it looks perfect (or perfectly imperfect if that’s what’s called for)—undeniable, resolved—like it’s sprung fully formed from the head of Zeus.

On that note, I’ll point out that the underlying theme of Eberle’s work has to do with the mythologies mankind has built for itself in the face of staggering cognitive dissonance. Eberle’s a walking, breathing bullshit detector who knows how to charm the pants off a viewer while pointing out just how corrupt and deluded our species can be, and just how far we’ll go to exploit and twist anything we can. He work doesn’t communicate outright rage, not explicitly, but at the bottom-most layers of her work’s meaning, there is some outrage. The destruction of nature and the willful oppression of women is a running theme of Eberle’s, though her treatment of it is never pedantic. In the end, she makes gorgeous objects that are material symbols of our darker history and future. This is the work that should be worth a fortune, and not just because it often involves precious materials.

Her show at Cris Worley’s is called the Mythology of Love, and it’s about how our collective hard-on for romance has skewed and deformed both the hard and soft reality of love. She’s made giant, grotesque perfume bottles, which are so fresh and surprising (the images here do not begin to capture their presence or the impact of any of the work in the show), and she’s used music boxes within sculptures, and created four distinct perfumes (one for each letter of the word “l-o-v-e”), and made a wall of flying ceramic bats. She’s hooked contemporary mythologies—including ones driven by advertising and consumerism—to the more ancient ones which were driven by superstition and religion, but the tone of the show is never heavy handed. It’s her bid to point out the absurdity of time always bending back on itself, because human nature never changes. It’s a dig at the idea of “the heart wants what it wants,” which Eberle knows is a piss-poor excuse for the self-indulgent, vain way we seek and define our experience of romantic love. In a way, she’s shooting holes in the very foundation of romanticism, while giving viewers a new set of weird and wonderful and very romantic things to look at.

Celia Eberle’s The Mythology of Love is at Cris Worley Fine Arts in Dallas through Feb. 13.