Anthony Romero and Josh Rios, both originally from South Texas, met in Austin and began working together while attending the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (2008-2011). Together, they create works that blur the mediums of the academic lecture and theatre, sculpture and performance to explore the experience of being Mexican American in contemporary society. Their most recent performance at Andrea Meislin Gallery in New York, Please Don’t Bury Me Alive!, teases out the not-so-veiled colonial impulses in Robert Smithson’s writing about his travels in Mexico and rescripts Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot to take place in a detention center along the U.S.-Mexico border. Romero and Rios juxtapose the role of the flaneur enacted by Smithson as he moves freely through Mexico with the figure of migrant or immigrant who is impeded from that kind of movement. Here, Romero and Rios talk to Risa Puleo.

RP: Where does the title Please Don’t Bury Me Alive! come from and what have you put together under this umbrella?

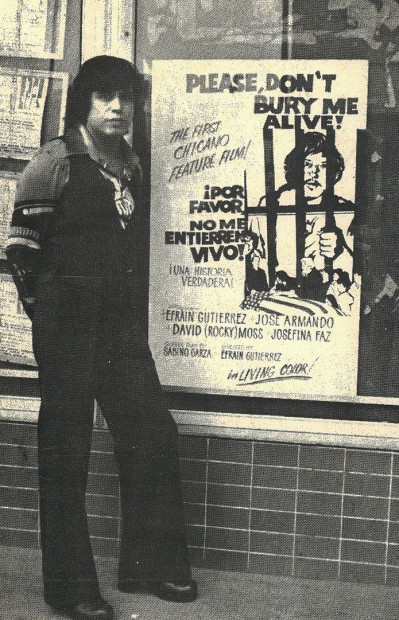

AR/JR: Please Don’t Bury Me Alive! is borrowed. Originally it is the title of a 1976 film by independent director Efraín Gutiérrez. Often considered the first Chicano film, PDBMA! was shot in San Antonio and tells the story of a young Chicano dealing with his brother’s death in Vietnam. We came across the film while doing research last year around Chicana/o moving image works—research that ultimately led us to curate a series of screenings that included performative and pedagogical components.

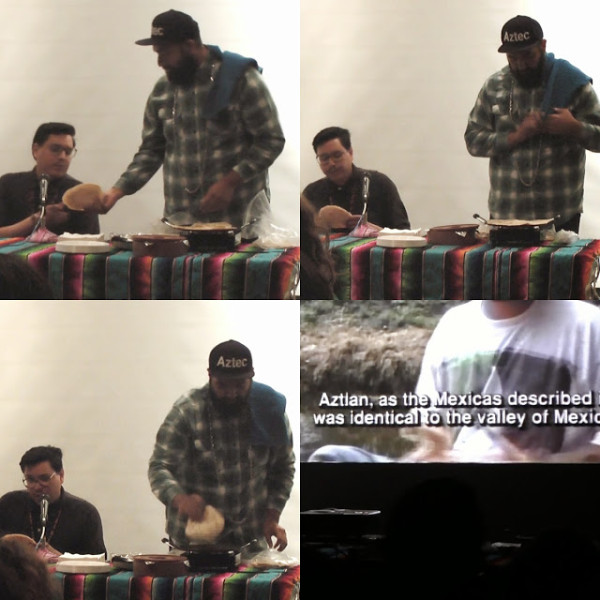

While in residence at Sector 2337 last spring we used the title to frame a two-part project: a performance-lecture and an ensuing installation. The installation featured various reformed sculptural elements from the Smithson lecture-performance, as well as an architectural intervention, some previously made framed works, and a small group of drawings by Chicano cyberpunk sci-fi novelist Ernest Hogan. Please Don’t Bury Me Alive! was really a way to gather all our thoughts at that particular time.

What we performed in New York at Andrea Meislin was the performance-lecture section of this expanded project, but we also mixed in some large print works that combined text from the Smithson lecture with images of the Chicano Moratorium riots. So much of what we do is tied to what we already did and what we plan on doing.

There is a lot of openness in our process and sometimes it’s a bit messy—but we like that. One nice thing about the complexity of the title, its origins, and the various iterations of the work that exist under the name is that when searching online you are likely find our performances and installations alongside Gutiérrez’s film, which incidentally has been remastered by the Chicano Studies Research Center out of UCLA. We deployed a similar title strategy in a previous project called Richard Serra is a very important Latino Artist. When you search these words online our work is likely to come up in proximity to Serra, something that would never happen otherwise. Basically the answer to a seemingly simple question has all these paths it can move down—a direct result of our interest in research as a basic element of production and our interest in process.

RP: Watching your performance of Smithson’s text as a script, rather than reading it in a book, radically shifted my perception of his project and drew out colonial subtexts that are somewhat obscured. How did you approach the text?

We approached the text tentatively, but also with intense interest. It was a surprise to find it and read it, and we knew right away that we would be using it in some way. We continue to struggle with how we feel about Smithson’s words. It’s very offensive in many ways; one passage in particular claims flatly that Mexico is a violent and dangerous place, both historically and contemporaneously. He’s not referring to criminal danger, but something psychic and ontological that supposedly exists preternaturally in the very Mexican soil. His comments are full of a strange anxiety. By choosing to recite passages like these, we are choosing consciously not to turn away from Smithson’s racism but towards it. To move it around in our mouths, to deal with with it on the level of materiality. Our hope is that this tension is visible in the performance, that it goes back and forth between reciting the text and communicating a dislike at the same time. Embodying the text really does help reduce its power as an abstraction, bringing it back into the social fabric, which in turn reveals how it echos certain colonial fantasies. Clearly, a major part of the performance is about embodiment and control.

Your earlier observation on how the performance moves back and forth between Smithson’s colonialist travelogue and the migrant trapped in a state of detention is very prescient. The nuance between the various levels of privilege people have to move about freely has always been a pressing subject in the U.S., but may be even more pressing in today’s political climate. The ability to move signals a host of other privileges and power relations. It matters who is moving and under what conditions, something we make both these texts clarify through our embodiment of them and our rewriting of them.

RP: Your work straddles an interesting mix of performance, re-performance, recitation of texts and scripts and the academic lecture. Can you speak to how you brought these different mediums together and how the speech act functions in your work?

AR/JR: In educational institutions you give a lot of lectures and go to a lot of lectures. Our practice is rooted in the experience of being historians, writers, and scholars, and for that reason we are concerned with the acquisition and production of knowledge. But we are also concerned with the formal qualities of knowledge, how space and architecture function as supplements to expertise, how objects and spatial arrangements communicate expertise. The podium, for example, is a very interesting armature that made perfect sense for us to work with. Our podium is built from cheap materials and copy machine prints, so there is no official archival life for it. Despite being made of very temporary stuff it still supports what it needs to support at any given moment. The research material which makes up the podium surface is comprised of a history of Chicana/o art from the ‘60s to now. One of the reasons we took the invitation to perform in New York was to create a situation in which the history of Chicana/o art-making could be present in a gallery in Chelsea, even if we had to smuggle it in. The podium makes a claim about the way certain marginal histories operate within the U.S.’s larger national narrative. It also gives those neglected and erased histories primacy and claims a space for them to be projected to a public.

Regarding the act of recitation, the speech act allows for simultaneity—an experience of the text and its embellishment by the voice and the body. As artists who are concerned with language, being able to expand the formal and material qualities of text through the voice and the body is very generative. In some ways it’s no different than how the images or performance props function in relationship to the text. They also aid in the expansion of the text into a context. Recitation and reenactment opens up the material, allowing it to grow through our interpretation, its staging, and its reception by the audience. It’s our way of giving life to the archive.

RP: Chicago and Austin have both been historic sites of Chicana/o art production. Do you see your project as existing within this legacy? What can you do in Chicago that you can’t do in Texas, and vice versa? How are they similar and how are they different in your experiences?

AR/JR: This is a difficult question, partially because it’s difficult to think of ourselves as working within a legacy when so much of what we are doing is about making these histories visible to publics who might not otherwise encounter them. It’s also challenging when these legacies are hidden to us as well. We are doing as much discovery as making. Maybe our recent practice falls within the tradition of politicized consciousness raising. We research, talk, and have realizations, often times as we learn new things about our supposed legacies.

One of the main differences between the Midwest and the Southwest or Chicago and Austin is the border. What would Tejanismo be without the particular set of socio-historical circumstances that brought the state of Texas into being, including the chain of events that took the land out of indigenous hands, passed it along to Mexico, and finally to the U.S.? There is a way in which the Southwest is determined by a migration of borders more than a migration of bodies (we didn’t cross the border, the border crossed us); whereas the Midwest, for Chicana/os, is purely about the movement of the body. It’s the history of labor trails that allowed for there to be communities of Chicanos in places like Chicago.

RP: This is an interesting take on a project involving the politics of identity, which historically has tended towards issues of representation. Your project seems to be expanding that notion into issues of visibility.

Representation can mean a lot of things of course, not simply figuration. It is as much a concept or idea as it is an image. If we consider the inheritance of images and cultural activity given to us through the Chicano Civil Rights movement, the work had to have a political overtness that may not be required in the same way today. Those early images of the 1960s and ’70s were about gathering an imaginative community, creating a social consciousness that was not simply given, so the visual and cultural production was directed towards these ends. But it was very conceptual as well. If we consider, for example, the emblematic UFW icon of the black eagle in a white circle on a red background we can immediately see a very sophisticated navigation of history and visual design: there is the call to proletarian revolution across time and continents, there is the call to Mexico and the mythologizing of Aztec society as a refined and complex pre-Columbian culture; there is even the call to consider the role design plays in everyday life. The reflexivity of the image is all concept. It needed to be reproducible by a wide range of activist, protesters, and organizers who may or may not have had art training. Its minimalistic aspects were so purposeful. These are the kinds of nuanced aspects of cultural production that get lost in the loss of the overarching story.

RP: How do you balance approaches that are often positioned as antagonistic? In other words, how do make work about identity without being limited to representation or approach identity politics after David Hammons?

For us it’s more a question of using our cultural heritage as a way to intervene into dominant narratives that surround conceptual and pedagogical practices. We are weaponizing ourselves in a way. This is not to say that there is an antagonism in the work; we, like many artists of color, are certainly susceptible to that kind of communication. But, we hope the work offers up an alternative. We often speak about the privilege of white artists to dismiss critical reflection under a presupposition that their work circulates as a self-evident universalism. Is there any reason that Chicana/o artists can’t also make that kind of assumption? At the same time we have to be very careful about assuming universality. We wouldn’t want to reproduce all the political and social problems such an assumption brings with it. We do a kind of strategic universalism, deployed at certain times to arrive at formal and conceptual decisions, but it always has to find its way back to our experiences.

We are trying to develop culturally-specific formalisms. What does a Chicana/o aesthetic look like now? What is the difference between a Chicana/o aesthetic and a Xican@ aesthetic, a Latinx aesthetic or even a Mexican-origin aesthetic. How do we build a formalism out of an ethnically and culturally specific visual language that is linked to larger imaginary socialities? This kind of tentative and evolving aesthetic is in some ways more available to us than a fully conceptualized Chicana/o identity. The idea of the stable Chicana/o identity is somewhat problematic because it levels all the nuanced expressions that various brown populations have experimented with while living under a variety of circumstances across history. To say ‘Chicana/o’ is in itself a kind of negation as it immediately begins to conjure up its own differences.

In November, Josh Rios and Anthony Romero will be in residence at Harold Washington College, where they will revisit Ernest Hogan’s practice, alongside inquiries about post-colonial science fiction and critical imaginaries of the future. In December they will be participating in Chicago’s Poets Theater Festival. All images courtesy the artists.