On his website and business card, San Antonio native Rolando Briseño lists his profession as “Cultural Adjustor and Public Artist.” He employs the former label (which he appropriated from the late Mel Casas) to refer to his primary objective as an artist. Considering San Antonio to be the most truly Mexican city in the United States, Briseño has committed long-term to raising awareness about San Antonio’s Mexican heritage, and to push the art world to be more inclusive of Latino artists. Although his art is often politically charged, Briseño’s interests lie in the scientific and philosophical realms, as his attacks on social injustice are usually veiled in imagery that explores our relationships to one another and to the cosmos. And his work is often very public: since 1983, Briseño has completed numerous public art commissions, with the most recent being a design for a station at the Houston Metropolitan Transit Authority.

After earning BFA and BA degrees from the University of Texas at Austin in the mid-‘70s, Briseño became the youngest member of the pioneering San Antonio-based Chicano collective, Con Safo, and also exhibited at one of the city’s first alternative spaces, the San Antonio Museum of Modern Art (SAMOMA). In the late ‘70s, he headed to New York City to receive his MFA from Columbia University.

While living in Brooklyn in 1985, Briseño was chosen to represent the tri-state region (New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania) excluding Manhattan in the third “Awards in the Visual Arts,” a national traveling exhibition organized by the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art. During the 1980s, Briseño made brief visits to San Antonio and, following a studio fire in 1985, he spent a year in Italy and Spain. In 1994, the artist returned permanently to San Antonio, where he continues to work.

Powerman at the Table, 1982, enamel on wood and masonite, 84 1/2 x 42 1/2 in; Fighting by the Table, 1983, enamel on wood, 96 x 63 in.

In graduate school, Briseño’s professors had proselytized heavily for minimalism. During the same period, the Whitney Museum of American Art presented the landmark exhibition “New Image Painting,” which reinstated the legitimacy of figurative painting, with the particular brand characterized by cartoonish figures rendered with vigorous paint handling. In his works of the early ‘80s, Briseño responded to both of these developments, while introducing topics of personal relevance that have been central to his art throughout the years. In shaped works made by painting cut-out structures of wood and masonite, his images of tables are rendered in a simple geometric format, while figures are executed in a sketchy style and presented as caricatures. For Briseño, the table holds an important position in cultural life as the locus of community, where people gather to dine, converse, and fully engage with one another. Powerman at the Table and Fighting at the Table function as a staging areas for personal symbolism as well as for the enactment of narratives that investigate archetypes of masculinity. In Powerman, four empty plates imply that the action has yet to occur, while the hybrid figure who is at once businessman and muscleman fuses two different masculine stereotypes, bringing to mind the pop-culture persona of Clark Kent and Superman. In Fighting, Briseño examines the nature of human survival by juxtaposing the food that we eat to stay alive with an aggressive masculinity represented by boxers.

The Annunciation, 1989, acrylic and oil on wood, 96 x 116 in; At the Proton Table, 1991, acrylic and oil on wood, 48 x 83 1/2 in.

By the late 1980s, the table assumed a more prominent position in Briseño’s shaped paintings, which were now executed in the gestural style that was popularized by the Neo-Expressionist painters from the once vibrant East Village scene. In The Annunciation, Briseño depicts the art historical figures of the Virgin Mary and the announcing angel as feminine and masculine archetypes, rendering them in pink and blue respectively. Performing an ironic twist on Old Master annunciation scenes, he cleverly reversed their usual placement in the composition (the angel is traditionally on the left), suggesting that assigned gender roles should be in flux rather than set in stone. He also subversively pokes fun at organized religion (the artist describes himself as a “culturally Catholic atheist”). With works such as At the Proton Table— an overhead view of three people sitting at a table—Briseño began examining relationships between culture and science. Interested in quantum physics and the idea that everything is always in movement at the atomic and subatomic levels, the artist superimposed spirals over the figures’ heads and on oranges on the table to indicate that all matter is composed of energy. Also visible in the table setting are a computer keyboard and monitor featuring an image of a chicken, which Briseño considers an important link within the historical and continuing food chain. At the Proton Table is one of the earliest examples of what Briseño now calls a “tablescape,” a term that recalls Con Safo co-founder Mel Casas’ “humanscape” (which refers to the drive-in movie screen motif that serves as a compositional frame for symbolic imagery in Casas’s paintings).

Gringo Table, 1993, acrylic on tablecloth, 41 x 44 in; San Antonio Fatso-watso Table, 1995, enamel on oilcloth tablecloth, 53 in. diameter, Collection of Susie and Peter Krulevitch, Pleasanton, California; The First Course of an Aztec Banquet, 1998, acrylic on tablecloth, 36 in. x 36 in.

Briseño’s interest in the table led him to undertake a deeper examination of food in the 1990s, during which time he researched the culinary traditions of his Mexican heritage and turned to painting his tablescapes on tablecloths, napkins, and dish towels, at times incorporating food into his materials. Documented in Moctezuma’s Table, the 2010 monograph on the artist which he co-edited with Chicano Studies scholar Norma E. Cantú, this extensive body of work examines 5,000 years of food history, comparing and contrasting a variety of cultural practices. In Gringo Table, the aerial view of At the Proton Table has been repeated, but heads are eliminated and focus is now on the act of eating. In this instance, the arms and hands belong to Caucasian Americans who are shown cutting into steaks and holding their forks American-style with their fists. While two television remote controls on the table link these diners to present-day culture, the underlying spiral configuration bonds them to each other as well as to the space/time continuum. With San Antonio Fatso-watso Table, Briseño calls attention to the multicultural eating customs of his melting pot homeland by organizing compositional sections like the slices of a pie, with variations in tablecloth patterning, skin color, and food type corresponding to the culinary practices of different racial and ethnic backgrounds. By contrast, The First Course of an Aztec Banquet compares the similar practices of two specific time periods and locations, the first being an ancient Aztec pre-meal ritual of presenting one’s guest with flowers and smoking tubes, and the other a contemporary American post-meal offering of a cigar.

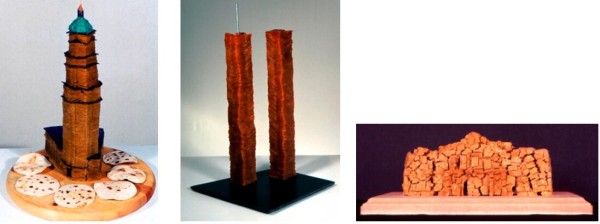

Tower of Life, 1998, corn and flour tortillas, ground chili, oil, 23 x 18 x 18 in; Twin Tortilla Towers, 2002, tortillas, chili, steel, 28 x 16 x 14 in; Masalamo, 2004, masa, 3 x 4 x 6 in.

While working with foods associated with Mexican cuisine, Briseño later began making sculptures from such materials, and went on to produce a number of fragile yet metaphorically powerful sculptural works made of tortillas, chili, and masa (corn dough). Following a path established by Joseph Beuys, who found symbolic value in his use of common lard as a sculpture material, Briseño fulfilled a similar purpose by using corn and flour tortillas to construct Tower of Life, which replicates an iconic 1920s building in downtown San Antonio that was built by mostly Mexican or Mexican-American laborers. In Twin Tortilla Towers, the towers were constructed from tortillas laced with red chili as a poignant tribute to the many Mexican busboys who were killed in the 9/11 collapse of the World Trade Center. Masalamo, a replica of the Alamo made from masa, was created to encourage discussion about the long tradition in American culture of distorting or overlooking the true story of the roles played by Mexicans in the history of the Alamo.

Cosmic Connection, 2007, archival pigment print, 17 x 22 in; Synergetic Scent, 2007, archival pigment print, 15 1/2 x 21 1/2 in.

With the growing ubiquity of digital technology in the early 2000s, Briseño began experimenting with the medium and produced a number of tablescapes by digitally altering photographic imagery. The most thought-provoking of these explorations is his Celestial Tablescapes series, which was exhibited in 2007 at San Antonio’s Galeria Ortiz in conjunction the with city’s annual photography festival, Fotoseptiembre USA. Inspired by an essay from the Swedish Brain Institute on pheromones that linked sexual attraction to the scents of erogenous zones, Briseño expanded his cosmological visions to include references to sexual appetite. In different examples, he compared heterosexual and homosexual attractions by photographing same-sex and opposite-sex naked couples posed on tablecloths on a studio floor. Viewing sexuality as merely one of the many energies making up the cosmos, Briseño floats the tablescape compositions in outer space. Flowers superimposed over the figures’ erogenous zones identify the locations of attracting scents, while phallic or vaginally shaped fruit appears scattered across the tablecloths as symbols of eroticism. To connect the figures to the present day, they are shown holding cell phones, which points to the relatively new cultural practices of using these devices as tools for sexting and hooking up.

Briseño’s recent forays into public art include both live performances and permanent site-specific installations. From 2009-12, the artist presented an annual performance in front of the Alamo on June 13, which is San Antonio’s Feast Day commemorating the arrival of Domingo Terán de los Rios at the Yanaguana River, later renamed the San Antonio River in honor of the saint. Entitled Spinning San Antonio Fiesta, the performance involved a group procession by Briseño and participants, leading to a ceremony in which performers would spin around a sculpture of Saint Anthony with the Alamo attached to the figure’s feet. Metaphorically, the revolving movement refers to the “spinning” of the official Alamo narrative, which for years had excluded the role of Tejanos from its history. In 2013, when the Daughters of the Republic of Texas lost jurisdiction over the narrative and a new land commissioner exhibited letters from Tejano heroes who helped win Texas’ independence, Briseño felt that things were improving, so he ceased presenting the performance. Nevertheless, he continues his advocacy for historical corrections by publishing annual editorials in the San Antonio Express-News on Feast Day.

Gateways: The Four Directions, 2010, San Antonio International Airport Terminal B; Puente de los Encuentros (Bridge of Encounters), 2012, McCullough Avenue Bridge, San Antonio; Puente de Rippling Shadows (Bridge of Rippling Shadows), 2012, Brooklyn Avenue Bridge, San Antonio

As a public artist, Briseño’s track record is extensive, and his commissioned projects are in (among other places) Brooklyn, Austin, Houston, and San Antonio, where three of his most recent efforts reveal a smart and subtle approach to cultural adjustment. An outgrowth of his food sculptures of architecture, the windows designed by Briseño for the San Antonio International Airport depict the facades of historical buildings throughout the city. In reference to San Antonio’s Mexican heritage, the imagery is presented in a style that mimics that of papel picado (cut out paper) and is rendered in the yellow color of masa. Elsewhere in the city, Briseño employed the papel picado style in the design of structures for two prominent pedestrian bridges, using red for one and blue for the other. Through his color use (when considered in combination), Briseño has already indirectly graced San Antonio with the beginnings of a rainbow. While this could be a perfect emblem for the multicultural understanding that his art has always sought to encourage, the rainbow has personal meaning for Briseño as a recognized symbol for LGBTQ equality. In 2014, he and his partner Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz made history by being the first (and as yet only) same-sex couple to have their marriage announcement photo published in the San Antonio Express-News.

1 comment

Great piece about a great artist! Thank you, David Rubin!