“Habsburg Splendor: Masterpieces from Vienna’s Imperial Collections” at the MFAH has everything: armor, a carriage, a sleigh, crucifixes, paintings of naked women, a painting of a hairy kid with werewolf syndrome, tapestries, walrus tusk and rhino horn tchotchkes, Roman statuary, ball gowns… . But then the Habsburgs had pretty much everything including a large chunk of Europe. They were a force on the continent for over 600 years. In addition to present-day Austria, at one time or another, Habsburgs controlled part or the whole of modern-day countries like Belgium, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Switzerland and Ukraine.

The exhibition is drawn from the imperial collections of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. The best way to view the show, which is somewhat awkwardly organized, is as a grand rummage through the Habsburg attics. Otherwise, you’ll end up mentally lurching back and forth through time trying to make connections between a Roman bust and a 17th-century painting, and a 19th-century field marshal uniform. It’s best just to enjoy the ride. There are spectacular things on view, among them works that have never left Vienna before, much less been shown in the states.

The show opens with a tableau of jousting knights on horseback and a lot of ornate armor, as fighting was a tried-and-true way to get and keep power. The helmet of the 1543 suit of armor for Charles V was specially designed to accommodate the prominent “Habsburg Jaw” that ran in the family. A 1553-55 bronze bust of Charles V by Leone Leoni evidences considerable mandibular excess even with probable artist flattery.

Amusingly, all of the suits of armor are placed on vivid red mannequin forms that have extremely pronounced, grapefruit-sized red codpieces. I am sure this is historically accurate in terms of fashion but it is a little distracting. (I kept wondering if there was a Habsburg Dick in addition to the Habsburg Jaw.)

More Habsburg jaws are on view in Jan Thomas’s bizarre 1667 wedding portraits of Emperor Leopold I and Infanta Margaret Theresa. A belated FYI to the Habsburgs, if one were trying to diminish the freakishly large chin of one’s family line: marrying one’s niece would not be the way to do it. The portraits were executed during their weeklong wedding festivities and the couple is clad in the absurd plumed costumes they wore when they appeared together in the musical drama, La Galatea. (The roots of the Viennese opera run deep.)

And speaking of absurd plumage, check out Jan Thomas’s 1667 painting Gundakar, Prince Dietrichstein in which the Prince is costumed for the “equestrian ballet” he led as part of the wedding festivities. He looks like a mardi gras float from a gay Krewe.

In addition to their matching orange, white and gold costumes, the newlyweds have matching jaws. Margaret Theresa was 14. She was not only Leopold’s niece, but also his first cousin. Her parents were uncle and niece as well. Gregor Mendel’s genetic research may have been a couple hundred years in the future but you would think basic animal husbandry should have been enough to clue these people in.

All this intermarriage may have been to consolidate power but inbreeding killed off the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs with King Charles II of Spain (1661-1700). His parents had been niece and uncle as well. Charles was apparently born with a host of disabilities. His jaw was so large he could barely chew, his tongue so thick he could barely speak and he didn’t talk until the age of four or walk until he was eight. He was mentally disabled and sterile. That didn’t stop the French king Louis XIV from marrying his niece Marie Louise off to him, the girl reportedly pleaded with her uncle to spare her.

But the Austria branch of the Habsburgs continued on and thrived, following the maxim, “Let others wage wars: you, fortunate Austria, marry.” Marrying to acquire lands and solidify alliances or familial intermarriage that recombined wealth and assets did allow the Empire more peace, stability and prosperity than more warlike empires. Empress Maria Theresa (1717-1780) was an extreme example. Andreas Möller’s portrait Maria Theresa as a Child shows the future ruler as a very poised ten-year-old. She was allowed to assume the title of Empress when there was no male heir available, and went on to rule for decades and give birth to 16 children, 13 of whom survived infancy. She married them all off advantageously, although things didn’t work out so well for her 15th child, Marie Antoinette.

Emperor Rudolf II (1552-1612) was one of the major collectors and patrons of the Habsburg dynasty, and his tastes ran to the surreal and the erotic. Barthomeus Spranger’s 1596 painting of Jupiter and Antiope is the kind of mythological scene that today would have its own fetish site. The misty paintwork looks like a soft-focus shot, as the nymph Antiope wraps her arm around the hairy goat-leg of randy Jupiter as he makes his move in the form of a faun. Her hand is just below his junk; you can almost hear the ‘70s porn-groove soundtrack in your head. Also in Rudolf’s collection is the misty eroticism of Corregio’s painting of Jupiter disguised as a cloud to seduce the nymph Io.

Rudolf II’s father, Maximillian II, commissioned a series of paintings from Guiseppe Arcimboldo of the four elements. On view at the MFAH is Fire, 1566. The endlessly inventive Arcimboldo is known for crafting portraits from painted objects relating to a theme. Fire includes a coiled match cord for the forehead, a crown of burning sticks with flames for hair. Rifle barrels and cannon barrels comprise the body. This incredibly surreal work has symbols of Habsburg might, like the imperial eagle and Golden Fleece, thrown in for good measure. In scrutinizing the image, Arcimboldo comes across as more of an illustrator than a painter. That isn’t a slight to the work, but you see how important carefully and clearly rendering each component item was to the success of the whole.

The exhibition includes delicate and frivolous objects like the fragile mid-eighteenth century “centerpiece for sorbets,” crafted from gold and shells. It’s quite lovely with cameos carved into pale pink shells. Six images decorate the curved arms of the candelabra-like structure, likely depicting Emperor Charles VI, Empress Elisabeth Christine, their three daughters and a son-in-law. Little carved shell baskets trimmed in gold dangle from each arm and would have held sorbet. It would have been akin to eating out of a Faberge egg. This is one of many works in the show that makes you wonder about the craftsman behind it. Who dreamed up and fabricated this engagingly silly object? What did it take to create it?

Habsburg excess is represented in a mid-eighteenth century carriage so large a window in the upper story of the MFAH’s Law building had to be removed so it could be craned in. It arrived complete with replicas of Lipizzaner horses to pull it. But the red and gold carriage looks restrained in comparison to the entirely gilded wooded sleigh from the same period. A baroque-style fantasy beyond imagining, its froth of ornate arabesques and shell forms completely obscure the form of the sleigh. It looks like a decorative centerpiece rather than a vehicle.

Among the religious artifacts is an early 1600s ivory and walnut crucifix of a gaunt and agonized Christ, by someone known as “Master of the Furies.” His arms are ridiculously long making the figure waver between elegant and grotesque. The Habsburg rulers also held the title of Holy Roman Emperor from 1453-1806 with a five-year interruption from 1740-45. (The Empire’s history includes some ugly periods of expulsion and oppression of Protestants.) Catholicism remains a major part of Austrian culture. In the 1950s almost 90 percent of the country was Catholic; today it’s approximately 60 percent, although single-digit percentages actually attend. The common Austrian greeting of “Gruß Gott,” literally means “may God greet you” but the phrase originally meant, “may God bless you.” Centuries of living under the Holy Roman Emperor leave their mark.

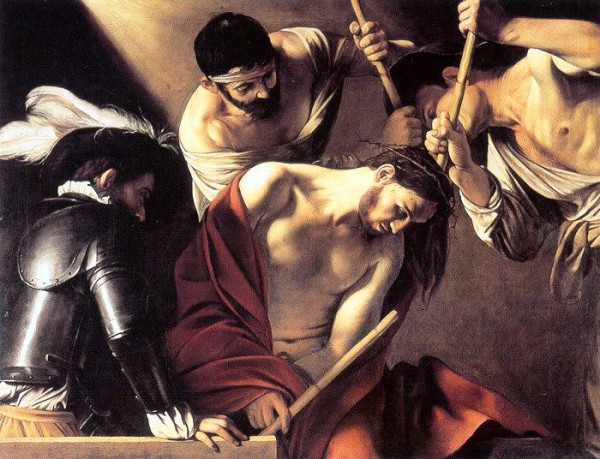

Caravaggio’s c. 1603 work, Christ Crowned with Thorns is on view. It is one of a number of stunning paintings included in the show. With chiaroscuro to spare, a stark ray of light angles across the torso of Christ as he sits surrounded by three male figures. This Christ is not the wracked gaunt stick figure of the “Master of the Furies” crucifix; Caravaggio renders the Son of God with smooth, well-muscled flesh. Christ’s head is turned to the side, a handsome face shadowed, his exposed, muscular neck the focal point of the entire painting. Caravaggio, ever frank and earthy, gives us his highly sensual version of Jesus.

The paintings are the strongest works in the show and the portraits are especially wonderful. Velázquez’ portrait of the Infanta Maria Theresa, 1652/53, will stop you in your tracks. The fourteen-year-old subject stands in a cream dress with spare coral pink accents, the seemingly casual brushwork coalesces in the figure’s softly rendered features and tactilely painted wig. You can almost feel the glossy smoothness of the wig’s ribbons and the hard luster of the pearls that decorate the neckline of her dress. This is one of several portraits painted and shopped around to various potential and politically important suitors (apparently the 17th-century version of Match.com). Maria Theresa wound up marrying the French King Louis XIV, her cousin.

Titian’s 1534/36 image of Isabella d’Este is haunting with the dark velvety green of the sitter’s dress, the delicate flush of her cheeks and the luminous red of her hair. Meanwhile Hans Holbein the Younger’s 1536/37 portrait of Jane Seymour, Henry VII’s ill-fated third wife has a cool, almost carved elegance. The details of her finery are so exquisitely delineated that they almost seem etched.

The exhibition closes with uniforms and gowns from the court of Emperor Franz Joseph who lived from 1830-1916. There are a lot of pompous-looking, gold-braid infested uniforms as well as some heavy-on-the-fur Hungarian ensembles. The showstopper in the gallery is a stunning black velvet evening dress with a tiny, Scarlet O’Hara-worthy waist. Its glamorous simplicity is executed in the style of Frederick Worth, who may have created it. It was worn around 1860 by Empress Elizabeth, known as Sisi, a 19th-century style icon with a fairly tragic life that ended when she was stabbed by an Italian anarchist in 1898.

The 1914 assassination of Archduke Ferdinand and his wife Sophie by a crazed Serbian nationalist would launch the carnage of WWI. Emperor Franz Joseph died in 1916, and a brief film clip projected on the wall shows some of the pomp and ceremony of his funeral.

His successor Emperor Charles would rule only two years. One of the most touching things in the exhibition is the ensemble worn by four-year-old Crown Prince Otto in 1916 for his father’s Hungarian Coronation. It’s a little gold brocade tunic trimmed in ermine with a matching hat. It has tiny white, fur-lined, leather boots embroidered with gold thread. A 1929 painting by Gyula Éder shows the toddler descending from his mother’s carriage in the furry finery.

Otto Von Habsburg was the last crown prince of Austria. He has been described as a fierce anti-Nazi and anti-Communist and worked for a united Europe. He spent most of his life living in exile. He died in 2011. His body was buried in Vienna’s Imperial Crypt. As per his request, his heart was removed and interred in the Basilica of the Benedictine Abbey of Pannonhalma, Hungary.

Hundreds of years of rule (and taxation) gave the Habsburgs the wealth to acquire and commission spectacular works of art. But they also left their mark on the European continent in terms of infrastructure and architecture. Their reputation as rulers varies across their former empire.

An elderly Hungarian woman I know says her father always thought the country’s division from Austria was a mistake. He argued that it was better to be part of an empire than an independent but small country. Meanwhile, a friend of mine from Zagreb observes, “They were tyrants but as tyrants go, they weren’t that bad. They didn’t destroy; they built. Their roads are still being used.”

A Bosnian friend concurs, “If I have to live under somebody’s thumb, between the Ottoman Empire who would impale you with whatever they could find to impale you, and the Austrian Empire, I would pick the Austrian Empire.”

“And,” his wife adds, “the most beautiful buildings in Sarajevo are from the Habsburg Empire.”

Some of the most beautiful art is from the Habsburgs as well.

“Habsburg Splendor: Masterpieces from Vienna’s Imperial Collections” at the MFAH through Sept. 13.

1 comment

Just last week I had a quick tour of this exhibit and was overwhelmed with the grand abundance. After reading your fine words, now I will return to actually see it in way that only your reviews can generate.

Thanks again, Barbara S.