Has your head ever exploded, perhaps in slow motion, from trying to wrap it around the enormous, amorphous idea of performance art? Curator and critic RoseLee Goldberg understands. “By its very nature,” she observed in her 1979 book, Performance: Live Art, 1909 to the Present, performance art “defies precise or easy definition beyond the simple declaration that it is live art by artists. Any stricter definition would negate the possibility of performance itself.”

In a 1980 issue of the Los Angeles art magazine Dumb Ox, artists Allan Kaprow and Paul McCarthy provided an encyclopedic list of the developmental sources of performance art:

futurism, Dada, surrealism, happenings, events, actions, body works, land art, conceptualism, environmental and action music, absurdist and structuralist theatre, concrete and action poetry, the dance of everyday movement, film, video, architecture, arts criticism….as well as outside art proper in radical politics and feminism, spiritual disciplines and rituals, education, spectacles, public demonstrations, sports, and the social sciences.

What hasn’t been perpetrated in the name of performance? Artists have tortured their flesh and had themselves shot as sculptural gesture. They have posed for extended periods of time as the opposite gender, as invented selves in fictive universes and in what we assume to be the real world, as persons living in a previous century. Many have undertaken durational tasks, journeys, and sagas. Some have publicly explored their sexuality in showy actions both beautiful and grotesque. Others have ripped into raw, intimate territory and shared their naked humanity as political statement. A surprising number have felt compelled to inform the world of their fetish for condiments.*

At times, we might view performance as the dry presentation of form and content for the sake of the presentation of form and content. As a laboratory for the study of human behavior. A ritual arena for shamanistic healing and discovery. A playpen for narcissists and exhibitionists—a perspective not entirely negative.

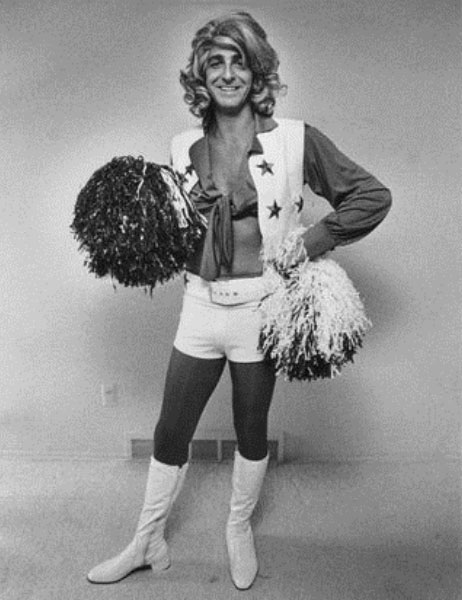

I’ve found it interesting to consider performance enacted in everyday life, outside the frame of an artworld context. Some years ago, for instance, a young insurance salesman named Barry Bremen from the Great Lakes area went to a Dallas Cowboys football game dressed as a Dallas Cowboys cheerleader. The man stole onto the field and managed to join the gals in a little cheerleading before security wrestled him away. Previously, Bremen had donned a professional baseball team uniform and hung out for a while in the dugout during a game. If the man had advanced his unusual hobby as a performance project—perhaps with a component of research on gender roles in sports—it would quite possibly be enthusiastically received and accorded a deserving credibility within the reference of at least some sectors of the contemporary art universe.

Barry Bremen, a.k.a. The Great Impostor, as a Dallas Cowboy Cheerleader (image via New Hampshire Public Radio)

Or take the case of Monsieur Mangetout (Mr. Eat It All), who appeared in Amarillo in 1979 to eat a waterbed as a promotional event for a local merchant. Mangetout was then scheduled to go to Tokyo and eat a helicopter. I was doing clerical work in a Texas art museum when I discovered Mangetout and fantasized that the curators would invite him to come and eat some of the less appealing items in the museum’s permanent collection as a performance event.

With that perspective, we might explore the genre’s wiggly origins in the oeuvres of such outsider pioneers as the fabled Oofty Goofty. I’d long thought Goofty was strictly a West Coast phenomenon, but I recently learned that he also lived for a spell in Texas. This new revelation did not make separating Goofty fact from folklore any easier, but attempting to make such distinctions would probably make the story a lot less fun.

At some point in the 1880s, sideshow promoters in San Francisco convinced a German immigrant named Leonard Borschardt to allow them to coat his naked body with tar and then cover the tar with hair. He was then placed in a cage and carny-barkered as a feral man-beast who ate raw meat and emitted wild grunts that sounded like “Oofty Goofty! Oofty Goofty!”

The tar and fur suppressed Mr. Goofty’s bodily function to the point that he nearly died. The act was short-lived, but the name stuck. According to the somewhat sketchy documentation of his career, Oofty’s next artistic endeavor could be interpreted as an early example of endurance performance art. Some accounts say that he carried a bat around in San Francisco, offering to let anyone slug the sense out of him with it for 25 cents. Other versions have patrons lining up to pound the doo-doo out of Oofty with uppercuts to the gut.

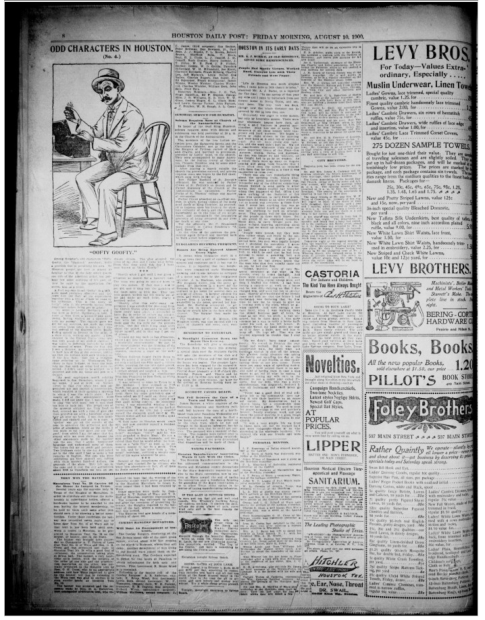

Oofty himself, in a 1900 interview with the Houston Daily Post, allowed that he did at one time have a gig with a San Francisco baseball team. If the team won, they paid Oofty $20. If they lost, they lined up to kick and curse the hapless Goofty. As he told the Post, the team was not very good.

Goofty told the Post that he moved to Houston around 1893, where his performing repertory expanded to the selling of simulated diamonds. (Before finding the Post article, I’d always been puzzled by a reference to “Oofty Goofty diamonds” in Frank Bushick’s 1934 opus, Glamorous Days in Old San Antonio.) And though he asserted that he was indeed a resident of Houston, his most documented Texas endurance performance was presented in the Oriental Hotel in Dallas.

Article on Oofty Goofty from the Houston Daily Post, Friday, August 10, 1900. (Image via University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History)

In 1897, as large crowds looked on, Oofty wolfed down an entire quail in one sitting each night for 30 days, consuming two of the birds on the final day and finishing off each bird by downing eight glasses of beer using a spoon and smoking a cigar in less than six minutes. The quail consumption may not quite sound like a remarkable performance, but for whatever reason, in the late 19th century a month of consecutive daily full-quail consumption was something of a nationwide rage, a feat believed to be all but impossible. A Waco postman at the time opined that the quail breast had a consistency more like wood than flesh.

Though the work of Houston artist Jim Pirtle is clearly more thoughtful, focused and intended for an artworld audience, he may to some degree be seen as a latter-day artist of the Goofty school. Pirtle began his own body performance as a child, pretending daily to suffer from a dramatic stomach virus and losing his breakfast to avoid school. “In hindsight,” he wrote in a 2013 artist’s statement for the Cue Foundation, “I see that my performance art was about that nine year old boy…. My performance ego was used to shocking his body by gorging on mayonnaise or picante sauce and then vomiting it out while singing Close to You. Certainly there were metaphors about living in the most egregiously consumptive society in the history of man and there were statements about masks, disgust and intimacy. But mostly it was about trying to help that nine year old boy to not hurt himself and speak up and become an emotionally mature adult.”

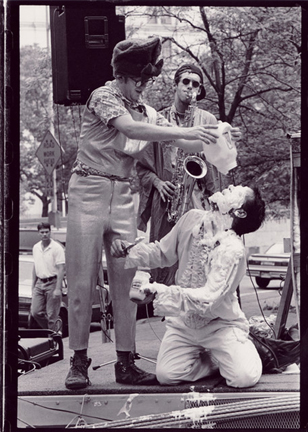

Jim Pirtle performing at Notsuoh. (Image by Michelle Lanter, via Lone Star Explosion)

Though he operates within the boundaries of the artworld, Pirtle’s awareness of the power of art was reaffirmed and galvanized by the art practice of an outsider he met in 1983 while working as an orderly at the Austin State Hospital. Working the night shift, Pirtle noticed that a patient named Ike Morgan would stay up drawing, mostly pictures of women and soul musicians. Establishing a friendship with Morgan, Pirtle began purchasing his art for coffee and cigarettes. After returning to Houston, Pirtle sold some of the work for Morgan, and before long, Morgan’s paintings of U.S. presidents and others were sought by galleries and collectors of outsider art.

In a text for Pirtle’s Cue Foundation exhibition, Museum of Fine Arts Houston curator Margo Handwerker wrote that Pirtle was “inspired by the desperation” he witnessed in hospital residents, incorporating the “voluntary convulsions” of his own childhood “into his body art-masochistic behaviors that ranged from pissing into a pint glass, then drinking from it, to singing lounge music while guzzling hot sauce and mayonnaise….these obscene antics evoke the visceral performances of Paul McCarthy and the violence of Viennese Actionism, while other events recall the chance of Fluxus works and the non-art of Allan Kaprow’s Happenings.”

Still of Jim Pirtle and Mark Flood from “Jim Pirtle is Forrest Gump,” 1995, in which Pirtle and other Houston artists and performers reenacted the Tom Hanks film.

Both Goofty and Pirtle often put their flesh, blood, and bone on the line for art. In 1900, Goofty claimed that in one of his endurance performances, he pushed a wheelbarrow from San Francisco to New York City. Nearly a century later, while Pirtle was rehearsing for a performance in which he jumped from a 12-foot ladder, the artist fractured his back.

Such a leap to flight reminds me of my imaginings of Yves Klein’s 1960 piece Le Saut dans le Vide (Leap into the Void). I’d long assumed Klein was actually leaping and often wondered about his reunion with terra firma, before I realized that the piece is a photomontage. Nonetheless, Klein believed he possessed the power to levitate. Referencing a painting by the Russian Suprematist Kazimir Malevich, Klein wrote, “Malevich was standing before the infinite—I am in it. You don’t represent or produce it. You are it.”

Jim Pirtle as Stu Mulligan in the New York City Buskers Festival, 1993. (Image by George Hixson via the Cue Art Foundation)

* For a more recent assessment of performance, Jens Hoffmann and Joan Jonas proposed in their 2006 book, Art Works Perform, that “culture—in particular the connection between ritual practice, staged situations, and the overall process of civilization—is now viewed as performance.” Underscoring the thin and often-invisible line between art and life, Hoffmann and Jonas cited the work of sociologist Erving Goffman as an influence, most notably his 1959 book, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life.

Gene Fowler is the author of many articles and books, including Mavericks – A Gallery of Texas Characters (2008), portions of which are reproduced in this article.