Best known for his distinguished body of portraits and self-portraits, Ángel Rodríguez-Díaz has also established himself as an accomplished printmaker and public artist. Born in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Rodríguez-Díaz moved to New York City while in his twenties and studied under Robert Morris, Ron Gorchov, and Rosalind Kraus at Hunter College, where he earned his MFA. Since 1995, he has lived and worked in San Antonio, where he was recently featured in the annual On and Off Fredericksburg Road Studio Tour and is currently producing a new print at Hare & Hound Press.

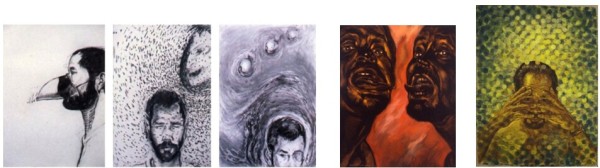

Over the years, Rodríguez-Díaz has produced numerous self-portraits, among the earliest of which is a series of charcoal drawings that he made in the mid-1980s while living the life of an emerging artist in New York. At the time working at a day job and dedicating himself to producing art at night, Rodríguez-Díaz drew a self-portrait daily as a means of coping with the typical frustrations of youth and of understanding his place in the world. In one drawing, he drew a phallic beak over his nose as a self-affirming symbol of his identity as a gay man. In another, he surrounded himself with sound waves to refer to inner voices advising him about a failing relationship. In a third example, he drew himself with one eye missing while a group of other eyes float over his head, a dreamlike scenario meant to remind himself to be astute about what is going on around him. In all of these drawings, the space surrounding the figure is active rather than passive, a feature that has become common to the artist’s overall oeuvre. In his 1991 double self-portrait Lenguas de Fuego (Tongues of Fire), Rodríguez-Díaz established a direct relationship between the figures and the background, which is painted in bold shades of red using abstract expressionist brushwork to echo the intense rage shown in the artist’s body language. Two years later, in Circulos de Confusion (Circles of Confusion), the surrounding space envelops the artist, having become a light-filled atmosphere composed of clustered dots. Here, peering pensively through his fingers in a pose of contemplation, Rodríguez-Díaz questions his position within the cosmos.

Left: Self-Portraits, mid-1980s, charcoal on paper, 26 x 20 in. each. Center: Lenguas de Fuego (Tongues of Fire), 1991, oil on wood, 19 x 16 in. Right: Circulos de Confusion (Circles of Confusion), 1993, acrylic and oil on canvas, 32 x 24 in., San Antonio Museum of Art

In his 1994 self portrait The Butterfly, Rodríguez-Díaz introduced a patterned background, a format that he has favored as a backdrop for his portraits and self-portraits for many years. Predating a similar move by Kehinde Wiley, Rodríguez-Díaz began employing patterning in an effort to bring elegance and splendor to the representation of his subjects, while at times also expanding the iconography. In The Butterfly, the exotic pattern of flowers and butterflies is linked directly to the butterfly headdress worn by the artist. Metaphorically, this adornment refers to Rodríguez-Díaz’s spiritual growth, which the artist views as transformative in the way that a cocoon becomes a butterfly. In The Spirit of the Head (2005), Rodríguez-Díaz shows himself holding a devilish mask, an allusion to his darker side. In The Good Old Days (2005), he portrays himself looking like a Roman emperor, winking and gesturing that all is okay. One of his most complex self-portraits, the painting is actually a commentary on American wealth and greed, with the artist playing the role of the oil mogul, whom he views as the new emperor of America. This idea is represented in the background through the depiction of oil derricks and, at upper right, a woman’s hand bedecked with jewels, shown holding a banner with the patriotic motto, “In God We Trust.” Conspicuously, the portion of the banner with the word ‘God’ is turned around and thus hidden from view.

Left: The Butterfly, 1994, oil on canvas, 50 x 50 in. Center: The Spirit of the Head, 2006, acrylic and oil on canvas, 36 x 24 in. The Good Old Days, 2005, acrylic and oil on canvas, 72 x 60 in.

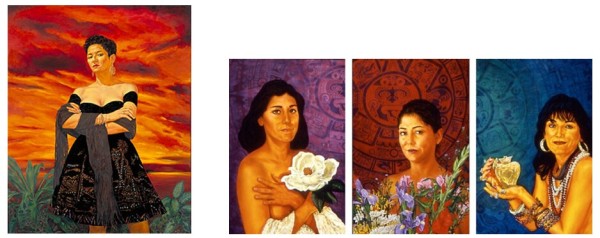

The majority of Rodríguez-Díaz’s portraits are of Latino figures who have been active in San Antonio’s cultural community, including the celebrated author Sandra Cisneros. For his portrait of Cisneros, the artist posed his subject in a heroic stance and placed her in a fiery Southwestern landscape to represent her dynamism, while also referring to Texas. With the composition based on Old Master portrait formats, the artist links Cisneros to a lengthy historical tradition. At the same time, a contemporary story is told in the embroidered sequins of Cisneros’s Mexican skirt, which form narrative imagery relating to her profession as a novelist. When planning a commissioned portrait of three sisters, one of whom is an avid collector of the artist’s work, Rodríguez-Díaz viewed his subjects as personifications of the Three Graces, and grouped the portraits to form a triptych depicting Hope, Faith, and Charity. To connect the women to their Mexican heritage, he chose a Mayan calendar pattern for the backgrounds.

Left: The Protagonist of an Endless Story, 1993, oil on canvas, 72 x 56 in., Smithsonian American Art Museum Right: Hope, Faith, and Charity, 2000, acrylic and oil on canvas, three paintings, 48 x 36 in. each. Collection of Sandra and Dr. Raphael Guerra, San Antonio

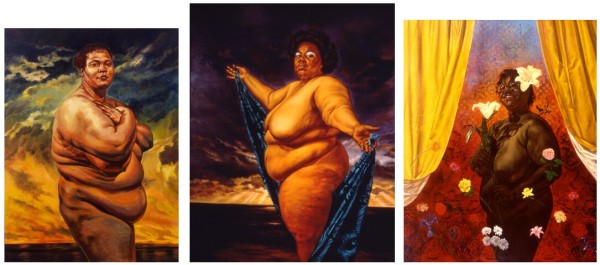

A triptych configuration based on the idea of the Three Graces had in fact been employed earlier by Rodríguez-Díaz for a painting project that he worked on over a three-year period. Painted during the height of the American multicultural movement and at around the same time that the Los Angeles-based Chicana artist Laura Aguilar was exhibiting dignified photographs of nude women of color, Rodríguez-Díaz’s Goddess Triptych (1991-94) offers his own contribution to the dialog celebrating the beauty of the non-Western ‘other.’ For the three paintings that comprise this monumental triptych, Rodríguez-Díaz had his rotund Latina subjects imitate poses from Old Master paintings (a practice that also foreshadows Wiley), and used titles referring to mythological goddesses from both Western and Caribbean traditions. It is also noteworthy that the three canvases are different sizes, an ode to non-conformity.

Goddess Triptych, 1991-94 Left: The Myth of Venus, 1991, 72 x 54 in., San Antonio Museum of Art. Center: Yamaya, oil on canvas, 84 x 68 in., Collection of the artist. Right: La Primavera, oil on canvas, 1994, 77 x 65 in., San Antonio Museum of Art

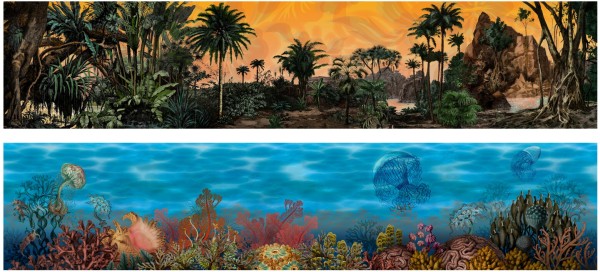

Rodriguez-Diaz’s interest in printmaking dates to his student days at the University of Puerto Rico, where he majored in the subject and learned how to use a traditional printing press. In recent years, he has produced screen prints at The Serie Project in Austin and, in 2013, he began experimenting with digital processes. To construct panoramic digital landscapes such as Tropical Landscape (2014) and Underwater Garden (2014), Rodríguez-Díaz scanned clip art from books, and then collaged and painted these elements digitally. He then had the imagery printed on fine paper using archival pigments. Composing on a computer monitor provided an opportunity to work with a very saturated palette, yielding a lushness that suggests paradise or divine beauty.

Top: Tropical Landscape, 2014, digital mural on 100% cotton rag paper, 13 x 60 in. Bottom: Underwater Garden, 2014, digital mural on 100% cotton rag paper, 13 x 60 in.

The artist’s repertoire of public art includes a mural at San Antonio’s Cliff Morton Business and Development Center and a window installation and several murals at the city’s new University Health System Hospital. While these works are seen mostly by people doing business at their respective locations, two outdoor installations that are viewable to larger audiences are already achieving landmark status. In 2008, Rodríguez-Díaz designed and installed an obelisk in the center of a rotary at the intersection of Blanco Road and Fulton Avenue in San Antonio’s Beacon Hill neighborhood. Entitled Beacon, the sculpture is constructed from steel sheets with ornate cut-out patterns, similar to those in the artist’s painted backgrounds. Organized into sections, the patterns reveal a cosmic scheme that from bottom to top includes vortices referring to organic growth, maguey plants that are indigenous to the Southwest and Mexico, clouds, the sun and its rays, and the moon.

The Crossroads of Enlightenment, 2014, steel, Blanco at Basse Road, San Antonio. The Beacon, 2008, steel, Blanco at Fulton Avenue, San Antonio

In November of last year, Rodriguez-Diaz completed another public monument featuring a similar cut-out steel latticework. Also situated on Blanco but at Basse Road, several blocks to the north of Fulton, The Crossroads of Enlightenment consists of two separate sculptures located at opposite sides of Blanco and shaped like the smokestacks of the nearby Quarry Market, which was once the Alamo Cement Company. In tribute to the Mexican American laborers who worked at the cement factory and were forced to live in a neighborhood known as Cementville to be close to work, Rodríguez-Díaz adorned his sculptural towers with cut-outs of flourishing images of nature. While looking glorious during the day, Beacon and The Crossroads of Enlightenment function as giant luminaria at night. Together, they express a reverence for the power and endurance of the human spirit, while illuminating the San Antonio landscape.