In my mind there are two key takeaways from a recent show of Jesse Morgan Barnett’s installed at the house of art collector, curator and critic Charles Dee Mitchell. One is that the show itself, titled JJIGAE, after a kind of Korean soup, is a solid outing by a young local artist who has been a visible presence on the scene for a handful of years now (though I nearly missed this show, and the general public will miss it, because it isn’t really open to general public). Much of the work is site-specific, conceived on the fly, and wouldn’t have been realized unless Barnett was faced with the possibilities and limitations of that particular domestic space.

In a regular gallery it would have been a completely different show, and likely a less surprising one. Here I see Barnett’s growth around versatility (he works with sculpture, text, painting, video, and photography), intimacy, and narrative, due in part (I believe) to working in this space.

The second idea I’m grappling with is how Barnett dealt with a problem all artists have to face, which is the one about context. Artists don’t always get to choose how or where their art is installed, of course, but they often have an idea of where it might debut, and proceed accordingly. By creating JJIGAE for the Mitchell house, Barnett contextualizes this body of work socially, politically, and situationally. It turns out he’s very clever.

Dee Mitchell is a board member of Glasstire, and a private person. Glasstire didn’t even list JJIGAE in its events section. I wasn’t sure I could or should write about the Barnett show at all, and didn’t even realize it was going on until Barnett himself reminded me. I barely know him.

But this weird situation itself compels me: Barnett’s show is the only case I can think of where a non-galleried artist has asked a very private philanthropist to give him a kind of residency in his house. The idea struck Barnett earlier this year when he was visiting his grandmother and aunt in a rural part of South Korea, a place he’s been to every summer for years. Both the discomfort and acceptance he felt in the gap between the culture of his ancestral home of Korea and his current life here (he was born in Korea but grew up in Kansas) was sharpened on this trip, and he wanted to respond to it.

As a co-founder of the ongoing Dallas Biennial series, Barnett understands how to resource unexpected spaces for showing work, though that usually means storefronts, lobbies, warehouses, etc. Here he wanted a house, and because he had once toured Dee Mitchell’s house as an MFA student (I don’t know if it was to see Mitchell’s art collection or the house itself, which is by architect Ron Wommack), that one came to mind. It is a good show space. He was still in Korea when he emailed a proposal to Mitchell, who he hardly knows, and Mitchell initially said no. Obviously in time Mitchell relented, but he wouldn’t remove his collection to accommodate Barnett. Barnett would have to work around it throughout the house. Burnett didn’t sleep there, but over weeks he built his show.

The corollary here is smart: being a guest in someone’s home means, even if that person’s house is less than an hour from your own, entering another culture. The routines, expectations, sounds, smells, humor—all of it is at least somewhat foreign, and the guest is expending tremendous energy staying conscious and respectful of this new world.

Barnett in Korea is a traveler. The cultural differences between Dallas and rural Korea are vast, as are the differences between Seoul and other Korean cities and the rural parts of Korea. In Barnett’s grandmother’s village, dogs are raised in tight cages and cooked up for dinner; pet cats are kept on short cables lashed to front porches. Both rural and cosmopolitan Korean approaches to aging and death, ritual and absurdity, technology, design, entertainment—all of these are a world away, as it were, from middle-class Texas.

Barnett attempts to take some ownership of the discomfort and nostalgia while understanding the futility of the gesture, and in turn he’s looking to discover a charmed or unexpected truth about the culture he’s known since childhood but never fully claimed. The exhibition is something like a distilled vacation slideshow, but here the narrative unfolds in odd spaces throughout the whole house.

Barnett is, after all, working to coordinate a deep familiarity (and therefore comfort) with some of the daily details of Korean life (the takeout soup, which Barnett replaces regularly; the slippers by the front door; the star-rating system dominating the kitchen) with a serious discomfort or confusion around some of the customs. He also allows you to use your intuition and desire to find patterns and meaning as you move through the spaces. For example: The video playing on the screen downstairs (this is Mitchell’s primary TV) is focused on the ancient feet of Barnett’s sleeping grandmother; they’re folded at the foot of her bed. Upstairs in the bedroom, a smooth white acrylic dome, just barely evoking the traditional Korean burial mound, rises up from surface of a bed.

Barnett is, after all, working to coordinate a deep familiarity (and therefore comfort) with some of the daily details of Korean life (the takeout soup, which Barnett replaces regularly; the slippers by the front door; the star-rating system dominating the kitchen) with a serious discomfort or confusion around some of the customs. He also allows you to use your intuition and desire to find patterns and meaning as you move through the spaces. For example: The video playing on the screen downstairs (this is Mitchell’s primary TV) is focused on the ancient feet of Barnett’s sleeping grandmother; they’re folded at the foot of her bed. Upstairs in the bedroom, a smooth white acrylic dome, just barely evoking the traditional Korean burial mound, rises up from surface of a bed.

The animal issue seems to be an unhappy one for Barnett, or maybe I’m projecting. But in the hallway gallery, Barnett has tethered a stuffed cat to a short galvanized cable and it’s positioned as though looking wistfully out a window (and then Mitchell’s real cat strolls by). It’s silly, but not funny. In the bedroom, a spare, four-foot painting on canvas is propped on a couch. It’s a portrait of a dog with his face washed out and little eyebrows added back in, which is both sad and funny, especially if one knows something about Korean personal grooming trends.

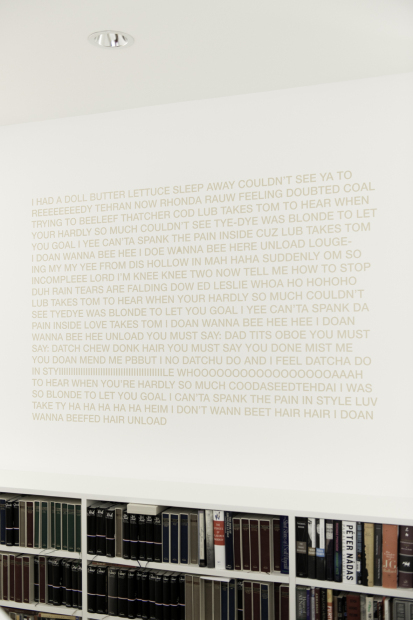

There are about a dozen pieces in all, just quietly doing their thing, and despite a pervasive melancholy, JJIGAE is spiked with a bit of the comic relief that comes with confusion or misinterpretation. One wall of the bedroom is emblazoned with the wildly distorted English interpretation found on a youtube lyric video for a famous Korean karaoke singer: “…CAN’TA SPANK THE PAIN INSIDE CUZ LUB TAKES TOM…” (which is still 100% more actual translating than I could attempt from English to Korean).

Fundamentally, Barnett is very aware that he can’t possibly reconcile how he thinks he should feel about his extended family’s old home and how he really does feel when he goes there, because he feels disturbed and amused and alienated and sentimental all at once. On some level anyone who tries to go “home” again—if by home one means an actual place that can’t compete with a memory forged years ago, or a wisdom that comes with experience—can relate.

But I have to return to the stealth of Barnett’s choice of location for the show. There’s so much going on with it. The hosting by Mitchell, however hands-off he is, is still a kind of sanctioning of the work and the artist by an important insider, which is in some ways even more validating than a commercial show in a local gallery. It’s cooler, so to speak. Also, the exclusivity of the house and getting to tour it adds to the show’s mystique. (A student group and their art professor were filing in as I was leaving.) It’s the opposite of over-exposed in this age of willful overexposure and social media, and it’s possibly therefore a better career move: the slow build as opposed to the risk of a trending burn out.

Plus, Barnett must have understood the various conflict of interests he was risking, due to Mitchell’s culture and media ties, and he must have found it worth the risk. And last but not least, since it takes extra effort to see the show, if it had been a clunker, all the art students and artists and critics, et. al., who had signed up for their appointment to tour it would have walked away unimpressed and Barnett would have come off like a waste of everyone’s (including Mitchell’s) time. This is true of any failed body of work, but Barnett’s not established enough to bounce back easily. But it is a good show, so Barnett just seems that much smarter.

JJIGAE, Jesse Morgan Barnett at the Charles Dee Mitchell residence, Dallas, Oct. 18-Nov. 15, 2014

Email [email protected] to make an appointment.

9 comments

Christina Rees is to be commended for recognizing this outstanding show by Jesse Morgan Barnett, as is Charles Dee Mitchell for hosting it!

I felt fortunate in having the opportunity of attending and the memories of Barnett’s kaleidescopic work as well as the experience keep returning entertainingly to my memory.

True, there is something about this young artist’s work, but I sense something great about the artist himself. There is no question that he is an artist at the very depths of his soul.

Collectors who own some of his early works will be fortunate indeed.

Hosting the Dallas Biennial is evidence of Barnett’s committtment to the artistic community of Dallas and the art world beyond.

There’s something that’s bothering me about this exhibition and I can’t put my finger on it. Perhaps the dregs and trolls of the Glasstire comments section can help me flesh it out? The work looks amazing and well thought out, quality stuff. However, there’s an air of elitism at play here, is there not? On the surface it sounds like your typical apartment gallery, no real posted hours, by appointment only, sort of like SOFA here in Austin, but, probably more on par with TestSite. Still the review implies only a select group will ever experience it. We (the general audience) were made aware of it only via this review. It’s filtered through an exclusive club of insiders. I’ll never see this show, and as Reese states it only works in this space (A strong definition for installation work).

Isn’t that filtering adding an untended something new to this exhibition? I doubt it’s Barnett’s intention, because the exhibition seems specific to identity and belonging. But without visiting or spending time with it, how will I know? I can only work off of what Reese lets me in on. This filtering privatizes dialog and isn’t that troubling? Help me out GlasstireTrolls™ because I’m looking for answers…

I posted the email one can use to make an appointment. So anyone reading this could make an appointment to see this show. The only reason it’s not public is because it’s in someone’s house. The exclusivity is more a matter of perception. Perception counts, yes, but it’s not fact.

House and apartment shows are more common in bigger cities with bigger art scenes, and I suspect every city will see more of this kind of thing in the coming years.

I agree this sort of venue has become prevalent, however it’s not limited to big cities. If anything it’s a platform frequently adopted in small-to-mid size cities. Austin, has/had TestSite, SOFA, Tiny Park & Red Space and numerous others failing to come to mind right now. I know Corpus Christi has The Living Room. Nor is this a new strategy. I am an advocate for alternate spaces like these, as well as others. As an artist they make more sense to me, than the cube.

I did see anyone could sign up for a tour. However, that’s only because, YOU, Christina Rees, posted it. YOU let us in on the secret. There was no opening (it’s a private residence, I get that) or announcement. You even wondered if you should post it. So what if, as you speculated, the show was a waste, would you have written this review? Would we have known about the show then?

RJ: Yes. And I was thinking of how the apartment gallery thing exploded anew in Brooklyn 10-15 years ago, and I did know Austin had examples of it (off and on). It hasn’t been too common in Dallas. Denton was doing it with bands back through the ’90s. The idea is cyclical? It’s punk isn’t it, in the right context. The domestic setting as venue been happening in various forms since the ’60s, and of course much, much earlier in some cities here and abroad.

About me having to post the appointment info for most of these readers to know about it: I think you’re right.

Apt gallery programs have been around 4ever, some effing great ones. My hope it that they will continue to thrive everywhere. This seems different (and fascinating) as an expression of a longish emerging and mildly disturbing trend: Installation as pseudo-intellectual interior decoration. It’s a quaint bourgeois gesture. I see it a lot. It’s also been rampant but recently in decline in the Dallas galleries; here it’s back as a kind of clearer manifesto – in that it effectively bypasses those commodity space(s). It makes perfect sense for it to thrive in D and it’s a decent way to make a living I suspect.

Yes! For Dallas, it feels downright scrappy. I’d like to see more of it.

And it goes both ways: some major galleries make their spaces look more like living rooms, or buy historic townhouses and the like to serve as their commercial exhibition space. It’s gimmicky, yes, but sometimes aesthetically pretty nice.

yes. the nature of the project has a note of exclusivity. the site is not a public space. The work considers being a guest in this space. Sometimes, the limitations of a situation provide interesting adjustments. Christina’s thoughts, placed in a public space, advanced the invitation into a position i could not begin with. Tour points, guest culture, rating systems… all contribute to the process and experience of “going and seeing things”. I would enjoy giving you a tour of JJIGAE at Charles Dee Mitchell’s residence RJ. [email protected]

I liked it