The Kindergarten of the Avant Garde: From Froebel to Legos and Beyond (via Brosterman)

Norman Brosterman’s marvelous 1997 volume, Inventing Kindergarten, long (and scandalously) out of print, has just been rereleased, thanks in part to a Kickstarter campaign funded by its many, many fans, affording the occasion for a fresh look at Brosterman’s beguiling thesis, and a bit of speculative jaunt beyond that.

Because “Inventing” is the precise word, for, as Brosterman elaborates, it’s not as though kindergarten always existed. It had to be invented and it even had an inventor. For most of European history, no one had bothered educating children before the age of seven, as it wasn’t until around that age that one might be confident they would survive into adulthood, so why bother? By the 1830s, however, it was becoming clear that if kids had made it to age four, they’d likely make it altogether; and this realization had a catalyzing effect on one German educator in particular, a charismatic crystallographer, of all things (and how often does one get to use those two words in one phrase?), named Friedrich Froebel.

Over the next several decades (through his death in 1852), Froebel elaborated an ever more specific theory and practice for the deployment of kindergartens (his term), small schools for children starting around age four, in which the kindergartners were the teachers—the gardeners of children—and the gardening took the form of guided free play: no tests, no drills, no grades, not even any reading, ‘riting, or ‘rithmetic. Just patterns and patternings (remember, Froebel started out as a crystallographer): a sequential exposition of and exposure to form and the formful.

Key to Froebel’s method was a succession of “gifts,” twenty of them in all, small boxes containing progressively more challenging materials and activities, which the kindergartner gave her charges, each in his or her own good time, as they became ready for them. The first gift, for example, consisted of colorful hand-crocheted yarn-wrapped balls from which emerged looped strings, perfect for tossing at kittens or spinning about one’s finger and in the process learning about centrifugal force.

The second gift consisted of a trio of little palm-size wooden objects—a sphere, a cylinder, and a cube—through play with which the child might gradually come to realize, for example, that the cylinder was sort of like a sphere and sort of like a cube. The third, fourth, fifth, and sixth gifts consisted of different sets of wooden blocks (cubes, rectangles, triangles sliced along their vertices, and so forth).

Then it was on to colorful paper parquetry tiles, and sticks, rings, jointed and interlacing slats, and eventually drawing exercises, and pricking exercises, and sewing (threads through sheets of stiff paper with gridded pinprick holes), and cutting and weaving and folding papers, and peas work (dried peas and toothpicks), and finally modeling clay—each gift elaborating on discoveries afforded by the one before, and all pitched to a spirit of adventure and self-expression.

And the thing of it is that, though Froebel didn’t really live to see it, during the decades following his death the kindergarten movement spread, initially throughout Switzerland and Austria and the German states, then throughout Europe, and presently (initially by way of German enclaves in the Midwest: the brewery towns of St Louis and Milwaukee) throughout the United States as well, where an entrepreneur-enthusiast named Milton Bradley took to mass-producing the various boxed gifts. By the 1880s, indeed, this sort of kindergarten was the predominant form of pre-school in the Western World.

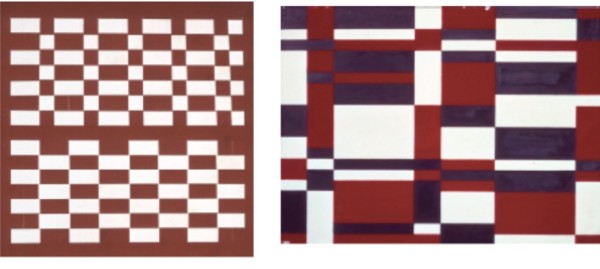

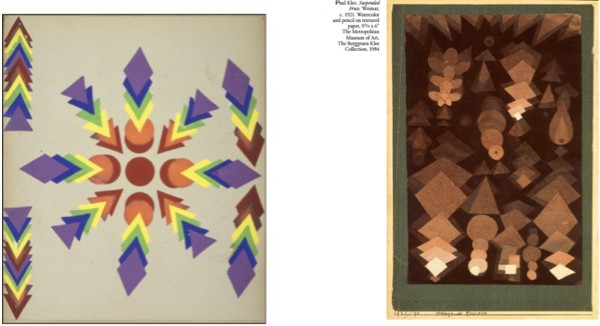

But it’s only now, in the last half of Brosterman’s book, that things really start to take off. Because that’s where he starts placing images of constructions or parquet work or sewing pages by unknown five-year-olds of the 1880s side by side with avant-garde masterpieces from the 1910s and 1920s—works by Albers and Mondrian and Kandinsky and Klee and Frank Lloyd Wright and Gropius and Le Corbusier and Buckminster Fuller—and you can hardly tell the difference.

US Kindergarten teacher Irma Crawford, 1909 (left) made with seventh gift (paper parquetry), Paul Klee, 1921 (right)

And indeed, as Brosterman mines the biographies and memoirs and late-career interviews of all of these twentieth-century masters, it turns out that, in case after case, they had a hugely influential mother or uncle or neighbor who taught kindergarten, that they’d all attended kindergarten, and each one in his own way testified that the germ of his entire vocation had been planted in those kindergarten experiences (Buckminster Fuller attributing the idea for the geodesic dome to his early games with dried peas and toothpicks; Piet Mondrian not only likely attending kindergarten—his father ran a primary school—but then training as a primary school teacher himself, during which time he’d have imbibed the sort of Froebelian rhetoric that would come to form the basis for his entire neoplasticist project; Le Corbusier, before his enrollment in art school, spending “ten years in programs based solidly on Froebel’s techniques, and during the very period when Froebelianism in his hometown” of La Chaux de Fonds, Switzerland, “was the purest and most rigorous it would ever be”).

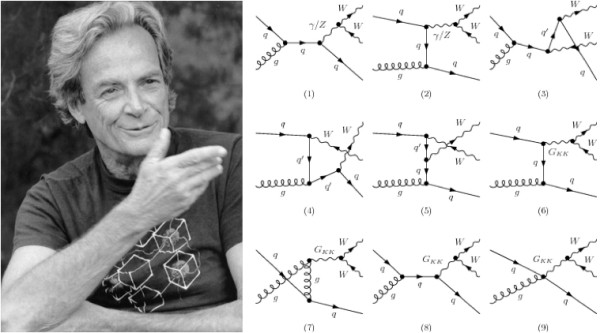

More recently, the physicist and science writer Margaret Wertheim, cofounder of the LA-based Institute for Figuring and an early champion of Brosterman’s work, has taken to probing further, into the backgrounds of the physicists and other scientists who took part in the great revolutions of the early and mid-twentieth century (people like Caltech’s legendary Richard Feynman), and here too she’s been uncovering countless references to the seminal importance of kindergarten (Feynman’s mother Lucille, for example, had trained as a kindergartner), a cascade of references that Wertheim had herself been turned on to by a marvelous post on UMass Lowell professor Sarah Kuhn’s “Thinking With Things” blog.

What we are given to understand across Brosterman’s and now Wertheim’s and Kuhn’s work is nothing less than the way many of the greatest avant-garde breakthroughs of the twentieth century were being incubated in the kindergarten classrooms of the nineteenth.

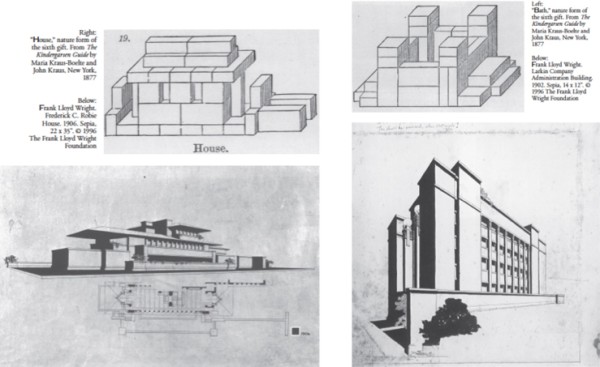

Take the case of Frank Lloyd Wright (born in 1867, fifteen years after Froebel’s death), in whose case kindergarten came by way of his mother, who’d happened to grow up a carriage ride away from the very first kindergarten in America, in Spring Green, Wisconsin, and who, early in her own married life, after the young family had moved to Boston, studied to become a kindergarten teacher herself. Frank’s 1932 autobiography is chock-full of references to the veritably life-defining lessons he derived from his own kindergarten experiences, and Brosterman’s book affords startling juxtapositions of the paper-folding and parquetry efforts of unidentified nineteenth century five-year-olds alongside early twentieth century Wright floorplans, the same with exemplary Froebel block deployments from an 1877 kindergarten manual and both the 1906 Robie House and the 1902 Larkin Company Administration building.

Indeed even the dimensions and proportions of the soaring cantilevered volumes of Wright’s iconic 1935-39 Falling Water residence can be seen to derive straight out of the wooden blocks from Gifts Three through Six that the young Wright would have handled as a boy.

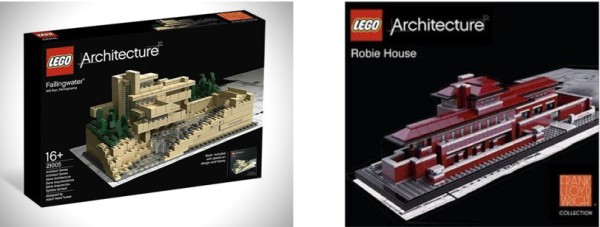

One amusing aspect of all of this is the way we’ve now come full circle, thanks to the Lego company, which has issued an architectural series of its own, inviting young enthusiasts to build their own versions of the Robie House and Falling Water and such other equally Froebel-besotted masterpieces as Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye and Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House.

Though, actually, that Lego series contains an implicit critique of the modernist project, or rather what happened to the kindergarten ideal when it morphed into modernist orthodoxy—all those stories of modernist architects, for example, who demanded that everything be just so, with not a single plane or vista altered, with every little instance of freeform decorative or ornamental play leached out; the rigid manifestos of the cubists and futurists and color theorists, with their insistence on specific methodologies, the very sorts of demands and insistences, that is, from which the next generations felt the need to wrest themselves free. To liberate themselves, that is, into all that authority-questioning free play that is the very essence of post-modernism, and as such, oddly, much more in keeping with the original spirit of Froebel’s project.

Such, curiously, was the theme of last year’s unexpectedly wonderful Lego Movie, a product-placement extravaganza if ever there was one, though one veritably pickled in the spirit of playful self-undercutting and cross-reference.

For the whole plot of Chris Miller and Phil Lord’s slyly subversive contrivance was that children, precisely, should steer clear of all the pre-programmed, rigidly model-based, instruction-enforcing prescriptions of the whole range of Lego Corporation offerings, such as those crazy Wright and Le Corbusier sets and all their formulaic brethren (represented in spirit in the film in the person of the dread corporate villain Lord Business and his legion of Master Builder drones), that instead, kids (like our hero Emmet the resolutely winsome Everyman) should instead launch themselves into a veritable Froebelian debauch. In short, they need to learn to kick free and play.

Lawrence Weschler is director emeritus of the New York Institute for the Humanities at NYU. His most recent book was Uncanny Valley: Adventures in the Narrative. A portion of this piece originally appeared as part of utopian fantasy on the Public Books blog, under the title “Back to Kindergarten: A Modest Proposal for a College of the Future,” which can be found, along with much else, in the Archive section of lawrenceweschler.com.

Speaking of Lord Bezosness, for those who might like to steer clear of Amazon these sorry days, the Brosterman book is also available here.