Guest-curated by Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro, The Nearest Air: A Survey of Works by Waltercio Caldas at the Blanton Museum of Art defies a chronological reading of Caldas’ work in favor of an atemporal presentation that champions his “unique position on art and its ethos.” This first solo retrospective of Caldas in the United States, which spans over forty years of his career, obscures more than it reveals. Its organization stems from a presupposition that an artist does not change, but instead relentlessly pursues just one cohesive goal, which for critics, curators, and historians defines his/her uniqueness. Caldas’ survey, a heterogeneous assembly of supposedly timeless artworks, erases crucial differences between individual works. It also effectively eliminates questions of context. Where and when the works were created are not issues under consideration, so the possibility of speculating on the reasons of their emergence is limited, too.

![Aquário completamente cheio [Completely Full Aquarium], 1981](https://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/fishbowl-600x420.jpg?x88956)

Aquário completamente cheio [Completely Full Aquarium], 1981

![O louco [The Madman], 1971 (detail)](https://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/louco-600x278.jpg?x88956)

O louco [The Madman], 1971 (detail)

While it is hard to determine whether the objects that Caldas deploys are ready made, found, or fabricated, they consistently read as of everyday life. As sete estrelas do silêncio [The Seven Stars of Silence] from 1970 contains seven large silver needles of various shapes, longer and shorter, straight and curved. In light of the infamous Institutional Act #5 (commonly known under the acronym AI-5) instituted by the Brazilian military regime in 1968, I cannot resist interpreting The Seven Stars of Silence as a covert political metaphor. Among many repressive measures, AI-5 sanctioned censorship of the press, media, and cultural production. The box of needles reads as a box of elaborate instruments, possibly surgical, as tools to be used to silence the opposition, to literally sew the mouths shut.

![Tubo de ferro, copo de leite [Iron Tube, Glass of Milk], 1978](https://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/milk-600x568.jpg?x88956)

Tubo de ferro, copo de leite [Iron Tube, Glass of Milk], 1978

Whispering Giotto

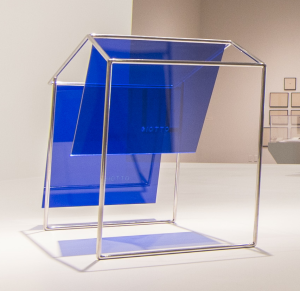

Finally, a large number of Caldas’ abstract sculptures and installations feature titles that refer to the so-called “great” painters, musicians, scientists and philosophers. Often the titles are also incorporated into the pieces in form of text. Such references—for example, his multiple evocations of Velázquez between 1994 and 2000—dominate the last twenty years of Caldas’ career. More often than not, these references seem to be arbitrary additions to elegant geometric objects. Why stamp the names of Picasso and Braque onto chunks of raw cotton? Why title the piece that consists of two highly reflective stainless steel circles mounted on a circular chrome frame Plato? Is the use of ultramarine-blue Plexiglas a sufficient reason to title a geometric sculpture Whispering Giotto?

What does a chrome cube lined with white rabbit fur on a black granite base have to do with Thelonious Monk, aside from three acrylic flags incorporated into the structure that spell out his name? These referential titles are illegible both in relation to the constitution and forms of the objects themselves and to the biographies and works of historical figures they cite. Limited to the icons of the Western canon that are ubiquitous in mass culture, they seem to be conscious attempts to inscribe the work into a specific, familiar historical lineage, much like the soundtrack of the greatest hits of twentieth-century music that accompanies the exhibition.

These three distinct aspects of Caldas’ oeuvre bring me back to the issue of context, or lack thereof. Born in Rio de Janeiro in 1946, Caldas emerged on the artistic scene of Brazil in the late 1960s, coinciding with the Brazilian military dictatorship (1968–85) that severely limited freedom of expression and political mobilization in the country. I do not intend to discuss the complex question of art’s political efficacy here, or delve into contentious debates on the subject regarding Brazilian art of the 1960s and 1970s. Yet, it seems to me that, in his early career, Caldas acknowledged the external non-artistic world around him, be it in existential or political terms. With time, his production shifted toward historical modernist idiom centered on the exploration of medium and perception, which The Nearest Air unabashedly privileges.

![Escultura para todos os materiais não transparentes [Sculpture for All Nontransparent Materials], 1985](https://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/nontransparent-600x342.jpg?x88956)

Escultura para todos os materiais não transparentes [Sculpture for All

Nontransparent Materials], 1985

The Nearest Air: A Survey of Works by Waltercio Caldas is on view at the Blanton Museum of Art, 200 E. Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd., Austin, TX, through January 12, 2014.

All photos are by Mary Myers.