When I walked out of Toby Kamp’s exhaustively researched exhibition Wols at the Menil, I felt as if I’d just walked out of a church. The anarchic Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze – like a priest given an unearthly sign – renounced his birth name and became Wols after a garbled telegram mangled his name.

Wols’ early drawings and watercolors bear the unmistakable stamp of Surrealists like Klee, Tanguy, and Masson, but his later oil paintings occupy an enigmatic space that opened up in European art after the trauma of two world wars, but before the hegemony of the United States made itself felt, and mid-century styles began to be catalogued by the art industry.

What was it about Wols and this brief, vague period in art history that gave me the impression I was looking at religious icons—an impression I never have after looking at Ernst, Magritte, Pollock or even Rothko? An important aspect of this misreading has to do with the fact that Wols is not exactly canonical. Virtually unrecognized in his lifetime and not very visible in ours, Wols is a blank page on which its easy to write our own stories, free from the limiting effect of canonization.

Drilled from the first survey course on the legacy and meaning of a Pollock it becomes nearly impossible to find in him anything other than the portrait created by Greenberg and LIFE magazine or the iconoclastic shattering of that image achieved by contemporary post-colonial readings. Walking into Wols with only a hesitant outline of who he is supposed to be, we project our own interests onto his work. The religious feeling was strongest in his oil paintings; the drawings and watercolors are too indebted to the stylistic conventions of early Surrealism to achieve the same blankness.

In the spirit of misreading and misinterpretation, articulated by Harold Bloom in The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry, I am going to ignore the Wols of the drawings and watercolors and focus on the Wols of the paintings and photographs—the Wols that burrowed into my own preoccupations and fixations, giving me a picture of an artist who would likely reject my interpretation of his works.

What is the greatest Western legacy of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries? Is it the steam engine and the industrial revolution? The automobile? The information and communication systems of the internet? I still think the greatest Western legacy of the past two hundred years is the deconstruction of the Christian concept of god and the assumption of an existentialist identity given utterance in Nietszche’s claim that “God is dead” and narrative in Sartre’s Nausea and Camus’ The Stranger.

This deep and relatively sudden change in the Western perception of belief in a higher power occurred during some of the most devastating violence the world has ever seen: the American Civil War, World Wars I and II, the Holocaust, Hiroshima and Nagasaki and Churchill’s scorched-earth bombing of Dresden (where Wols was born and spent his early childhood). For many artists, these events belied the concept of a loving God personified in the Christ of the New Testament. For those unable to let the idea of God die, it might have seemed like the Byzantine Christ Pantocrator had returned to slaughter the Jesus of lambs and children.

An entire generation of mid-century artists and writers had experienced the fact that no amount of Enlightenment-age progress could rid people of their tribal fear and bloodlust. And so they began to rebuild their lives in a world without a god or a rational system they could believe in, but with a deep need for ritual and belief. The Surrealists established a church complete with saints and manifestos, Art Informel built a kind of provisional meeting-house, while the American Abstract Expressionists cultivated a utopian belief in art that paralleled American nationalism and economic supremacy.

City of Dresden after bombing

Existentialism created a complicated portrait of what life might mean in the modern age of nuclear weapons, chemical warfare and little hope of salvation. Without ritual and significance, the corporeality of life becomes the shockingly meaningless kind of existence portrayed in Nausea. It is no coincidence that Sartre had some knowledge of Wols and wrote about him, although his perception of him and his work as the dark product of a life without significance seems skewed.

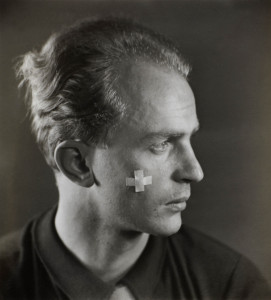

Unlike Sartre, I see Wols as a classically religious figure. In his photographic self portraits I see the holy fool—images that would be perfectly at home on the screen next to the anguished face of Renée Jeanne Falconetti in Carl Theodore Dreyer’s great film on religious conflict, La Passion de Jeanne D’Arc. His photographic still lifes of food that seems to be on the edge of decomposition and depictions of his seemingly dank studio have all the visual hallmarks of deprivation and asceticism that have come to characterize the monk in his cell.

But more than any other works in the exhibition, Wols’s oil paintings seem to me to have distilled the central composition and palette of religious icon paintings into a nearly abstract language.

![]()

Many of the paintings are quite obviously figurative, with eyes, mouths and torsos. The violent gestural painting in others evokes and even seems to represent viscera; blood, veins and flayed skin again evoking the suffering of classic Christian religious figures like John the Baptist, Jesus and any number of saints.

The Apostle St. Bartolomeo, Matteo di Giovanni, circa 1480

Several paintings are clearly representational and depict fish, hearts, a piece of bread or a radish—all objects that reinforce the notion of an ascetic diet and have strong connections to religious narrative and iconography.

Le Poisson (Fish), 1949

Wols died from food poisoning, a death that, to our contemporary minds, seems practically medieval, and adds to a sense of him as a religious artist.

For every association I see, another viewer could offer equally compelling alternatives, but my willingness to publicly offer such a subjective interpretation of Wols’ work has everything to do with the fact that the stakes of this misreading are low—I am able to see what I want to see without the fear of the monolithic but nonetheless fragile scaffolding of art history, criticism, and canonization crashing down on my head.

Wols, Voile de Veronique, 1946/47 or a piece of burnt toast

4 comments

Nice piece, Michael. The single painting by Wols I remember from the Menil always flummoxed me — I think you provide, with the accompanying illustrations, a persuasive entry point into the work of, as you point out, a neglected figure. Kudos to Toby and the Menil for presenting the work — wish I could see it. Now can we get Toby to take a look at Fautrier? Again, Michael, a nice thoughtful piece of work. Bravo.

I’d been meaning to check this out, and I went and saw it today after I read your piece. Really interesting show. I hadn’t realized Wols was a Schulze 🙂

Thanks John. It’s nice to hear from you. We miss you around here.

Thanks for the review Michael. We were planning to make the trip from Dallas to see the show, but then this ice storm hit. Hopefully we’ll get down there this weekend.