Filmmaker Charlie Ahearn brings glimpses of New York in the 80s to the Houston Cinema Arts Festival.

The best film document of the burgeoning hip hop subculture in early-1980s New York is not a documentary, but a low-budget narrative movie starring actual players from the scene as versions of themselves. Shot between 1981 and 82, Wild Style is not only the first hip hop movie, but I would argue it’s the only real hip hop movie.

This year’s Houston Cinema Arts Festival is bringing to town filmmaker Charlie Ahearn to present a special 30th anniversary screening of his classic Wild Style (1983), as well as the Texas premiere of his new documentary Jamel Shabazz: Street Photographer (2013) and a selection of short films he’s made over the past decade.

After being a founding member of the artists’ group, Colab, and making a few ultra-low-budget 16mm and Super-8 films, Ahearn teamed up with charismatic mover-and-shaker Fred Brathwaite (aka Fab Five Freddy) to embark on making a film centered around the art, music, and dance that had been brewing in the South Bronx and was quickly making its way to downtown Manhattan clubs and galleries. Given their goal of authentic portrayal, it may seem strange that they scripted it, but a degree of separation and slight translation proved to be smart and necessary. The film’s story, while minimal, was a skeleton on which to hang the documentation—a reason and a structure. It also gave a couple of backers something tangible to invest in, the non-professional actors just enough direction/distraction to act naturally, and the community something to get excited about. No one involved was thinking of this as a document for future generations to witness the humble beginnings of a global culture or a wasted and dangerous, yet culturally thriving New York City that, for better or worse, would one day be gone. They were just excited to portray the present moment and to see their expressions on screen in the same Times Square theaters that they saw B-movies and Kung Fu flicks. It was a city intervention similar to painting or writing on a subway car—an opportunity to interact, represent, and gain a little community fame.

The result of this slight mix of truth and fiction is unusual, though, and Wild Style should be approached as a unique, homegrown hybrid. The acting by the film’s non-professional cast is, by normal movie standards, pretty bad. But at the same time, it rings true, natural, likeable, and is especially fascinating given that the actors are actually the real-life, young innovators that they’re portraying. Lee Quiñones and Sandra Fabara (aka Lady Pink), who star in the film as Zoro and Rose, were known subway graffiti artists and a real-life couple at the time. In fact, nearly every person in the film—whether featured character, artist, musical performer, or just in the backgrounds of shots—is a notable from either the early hip-hop or downtown art scenes, or both—all basically playing themselves.

in the film—whether featured character, artist, musical performer, or just in the backgrounds of shots—is a notable from either the early hip-hop or downtown art scenes, or both—all basically playing themselves.

A good example of Ahearn’s approach of slight but respectful intervention is in the handling of the film’s music. In those days, DJs were cutting up known soul and funk records behind rappers. But in order to avoid potential copyright issues, Ahearn asked Brathwaite to work with musician friends (including Blondie’s Chris Stein) to record original, similar sounding grooves for use in the film’s live performances. They pressed these proto-breakbeat tracks on vinyl records and gave multiple copies to the DJs in advance to select and manipulate however they wanted. The result was great, authentic live music that was also unique, original material. In so many ways, Ahearn and Braithwaite observed the scene, distilled basic elements, formulated a few things, and then tossed those back into a creative conversation with the people, scene, and environment that was inspiring everything. This organic, back-and-forth approach is what made it possible to capture what no straight documentary could have, and what none of the slicker narrative movie productions that followed would even attempt.

Hip hop heads will explode upon seeing the on-screen world of New York streets, subway cars, trainyards, and clubs populated by a sea of young pioneers. Busy Bee, Cold Crush Brothers, the Fantastic Freaks, Double Trouble, Queen Lisa Lee, and others rock the mic in the small Dixie club and the film’s final outdoor concert. There’s DJ Grandmaster Theodore–didn’t he invent scratching? Crazy Legs from the Rock Steady Crew is on the floor. Graffiti legends Dondi and Zephyr. Is that Futura in the background? There’s Rammellzee. Ooh–DST. What?–Grandmaster Flash rocking turntables in his kitchen? Real rap rivals the Cold Crush Brothers and the Fantastic Freaks in a classic, West Side Story-style basketball court rap showdown?! Art nerds will recognize folks too, including underground film actor, East Village club fixture, and FUN Gallery co-founder Patti Astor, and even the infamous Glenn O’Brien playing a gallery owner. But even for those unfamiliar with the people, legends, contexts, and trajectories bouncing around here, Wild Style’s  authenticity is obvious, its sincerity is contagious, and its existence seems miraculous. In fact, it’s so entertaining and endearing, one almost forgets that these creative activities were radical–experimental, irreverent, and even illegal. That ten years before this, none of hip hop existed, and ten years later, it would be thriving and cross-pollinating across the country and on every continent.

authenticity is obvious, its sincerity is contagious, and its existence seems miraculous. In fact, it’s so entertaining and endearing, one almost forgets that these creative activities were radical–experimental, irreverent, and even illegal. That ten years before this, none of hip hop existed, and ten years later, it would be thriving and cross-pollinating across the country and on every continent.

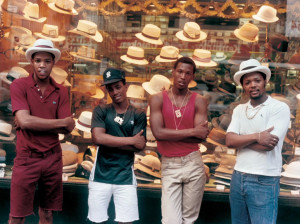

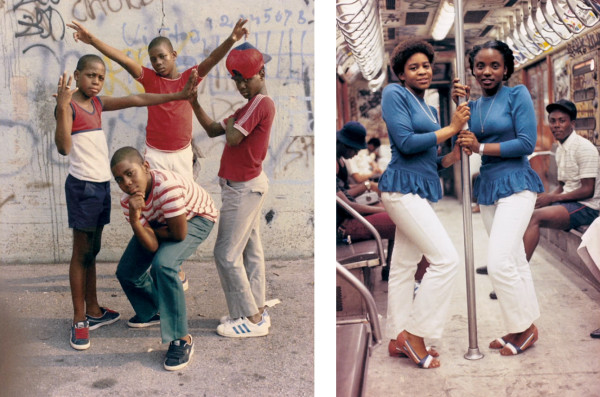

Like Ahearn’s Wild Style, Jamel Shabazz’s extensive photography–impromptu portraits of mostly African-American New Yorkers taken on the streets of Brooklyn, the Bronx, Harlem, and lower Manhattan in the late-1970s and 80s–comprises one of the most natural and authentic visual records of the era, yet were not completely “objective” documentations. Ahearn’s new documentary, Jamel Shabazz: Street Photographer, is a great showcase of a variety of Shabazz’s photos and an exploration of the stories behind the photographer and his subjects.

in the late-1970s and 80s–comprises one of the most natural and authentic visual records of the era, yet were not completely “objective” documentations. Ahearn’s new documentary, Jamel Shabazz: Street Photographer, is a great showcase of a variety of Shabazz’s photos and an exploration of the stories behind the photographer and his subjects.

The life-long street observer and career correctional officer’s work went largely unseen for decades before popping up in a couple of magazines and the eventual publishing of the book, Back In The Days. Initial interest was in their documentation of fantastic vintage clothing styles and a unique perspective on a long-gone, mythologized New York. Those are strong, fascinating elements, but past the fly coats, fresh Adidas, and old-school boom boxes, there are stories told in the faces and stances in these photos. Far from a fly-on-the-wall observer, Shabazz engaged his subjects. He talked with people, encouraged their personalities, and sometimes suggested a nearby wall, fence, or storefront as a good backdrop. This gave folks a level of comfort with his camera, and time enough to straighten their gear and come up with their own positions. This was not how the stranger passing by would see them, but how they saw themselves. People’s pride, strength, and beauty come through and activate their surroundings and fashion flourishes. Shabazz is as active today as ever, connecting and photographing the people around him.

Ahearn will be in attendance for these festival screenings, and I’m sure will have stories. Go! And thank him, and tell him to pass along thanks to Mr. Shabazz, too. Their invaluable documents provide fascinating glimpses of New York in an important time of transition, remind us of the power of rocking fresh styles with pride, and show us that real truth is found through connection and interaction as much as in “objective” observation. And you don’t stop.

Jamel Shabazz: Street Photographer (2013) screens Friday, Nov. 8 (9:15PM) at Sundance Cinemas (A morning screening will be co-presented by Project Row Houses Friday, Nov. 8 (10:30AM) at the Eldorado Ballroom as part of the Festival Field Trip program.) Wild Style (1983) screens Saturday, Nov. 9 (9:45PM) at Sundance Cinemas. Hip-Hop Short Films (2005-12) screens Saturday, Nov. 9 (1PM) at Cinema 16