Squirrel fetus stew anyone? Homemade pipe bombs to destroy the “technical class?” Smashing windows as an initiation into homicidal mania? Pus-filled gums resulting from porcupine meat lodged at the base of a tooth after an especially chewy repast?

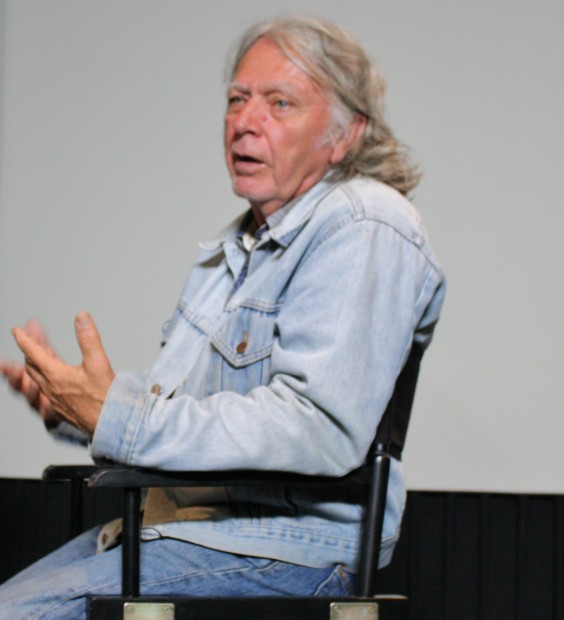

The story presented by James Benning in his film Stemple Pass of the solitary existence, profound and prophetic writings, and sociopathic acts of Theodore J. Kaczynski (the “Unabomber”) is nothing if not engrossing and enlightening. In an invigorating Q&A led by Richard Linklater at a recent Austin Film Society screening, Benning’s film unearthed serious questions about technology, humanity and the natural world, environmentalism, and teaching and tactics disruptive of the rise of machine culture.

Benning, like Kaczynski a mathematician who came of age in a working-class Midwestern family in the late 1950s/early 1960s, was able not only to get hold of Kaczynski’s secret journals but also managed to decipher their code (giving added significance to the filmmaker’s reprise of his subject’s words: “FBI, suck my cock!”).

Four thirty-minute static shots (one per season of the year) of a tiny cabin amidst a vast mountain wilderness comprise Stemple Pass. The non-chronologically ordered scenes are introduced by “ten seconds of black to cleanse the palette,” the given season’s name, and text stating the Kaczynski material—ranging from the early 1970s to 2001 and including journals, encrypted documents, the Unabomber Manifesto published by The New York Times and The Washington Post, and a prison interview—from which Benning reads in voice-over narration. In addition to his voice, we hear synchronously recorded sounds of the habitat: birds, the occasional motor, rainfall—although the director concedes some degree of manipulation such as “adding the helicopter.”

The cabin, situated on Benning’s land in the High Sierras, is a replica of the Unabomber’s hermitage in Montana. In his Austin introduction, Benning reported that he felt compelled to make it as a “counterpoint” to his already-constructed Thoreau’s cabin (Two Cabins, an earlier film, encompasses the set of replicas and another film in the series entitled Walden is forthcoming). The cabin houses a library of 115 books coalescing the collections of Benning and Kaczynski (although note that the existence of such is not foregrounded in the film itself). The artist calls this current cycle of work his “Two Cabins Project” (also referred to as “Cabin Project”), a series “being revealed in a number of different forms”—including the eponymous A.R.T. Press book.

The wild beauty of the opening section, “spring”: infinite textures and hues of foliage, triumph of curves over lines, symphonic rain—creates a ready space for and immediate sense of identification by the viewer with both the filmmaker and his controversial subject. Nature transcends. If Kaczynski’s yarns here of living off the land disturb in their extremity and malice toward others, they bespeak nonetheless a seemingly endless resourcefulness meriting if not respect then at least acknowledgment.

Kaczynski reorients his violence against things/property to homicidal pursuits, observing that one is a necessary step toward the other. In “fall,” Benning reads, “These journals make a small compact package easily concealed…They must be kept from everyone’s eyes..They contain accounts of felonies.” Less stunning overall than the preceding section, the image’s dramatic center is smoke billowing from the cabin’s chimney. Encouraged perhaps by my seat on the screen’s right (cabin side) to simply give in to the smoke’s hypnotic effect, I had to consciously avert my eyes in search of other spots to arouse and rest my gaze. Now recounted is the sugaring of gas tanks, stretching of wire across trails to disable and potentially kill motorcyclists, and dispersing of bombs to scientists and other members of the “technical class.” About one left in a Chicago parking lot, Benning as Kaczynski laments, “I wish I had some assurance that I had succeeded in maiming or killing someone.”

The third part, “winter,” features notebooks “containing a series of numbers” decoded by Benning in 2011. Snow: falling and subsiding—resonates with the earlier rain and, accompanied by intermittent mist pockets, composes a visual rhythm at once internal to the shot and at play with the film proper. A distant dog and a nearby bird form the most memorable parts of the soundtrack other than Benning’s recitation of Kaczynski’s texts. The slippage between filmmaker and subject (two characters) is especially uncanny in how Benning pronounces certain words awkwardly and sometimes stumbles upon phrases, backing up and repeating them. Such flaws remind the viewer of Benning’s presence and directorial purview while simultaneously heightening the reading’s sense of authenticity—not polished as in the representational but raw and visceral as in the experiential. Now the Unabomber is in full form: he details the planning and implementation of countless “experiments,” his “ineffective bombs driving [him] desperate with frustration” while being heartened by news reports that the FBI is “investigating.” In June 1985 he chronicles “success at last” when “experiment 100” results in a confirmed victim at the University of Michigan.

“Summer,” the final season, finds another approach to rhythm (and temporality) in the movement from light to dark of the setting sun. Benning reads from the 1995 manifesto as well as a 2001 prison interview, “Freedom means being in control of the life and death issues of one’s own existence.” The madman is most sage. “It is likely that technology will acquire something approaching complete control over human behavior.” What prescient critique of the post-millennial stage (just imagine all the “smart phones” that audience members will consult at first chance). Impossible to reconcile is Kaczynski’s capacity for life-affirming emotion: “The more intimate you become with nature the more you appreciate its beauty.” (Teachings of a terrorist?) “When you live in the woods the beauty becomes part of your life.” Cities turn subjects inward, woods outward. I am reminded of “Waldeinsamkeit,” the German word used to express “the feeling of being alone in the woods.”

From a life of solitude in which he plotted and enacted murder to carrying forth his writings (including weekly correspondence with a friend of the filmmaker) from a cell in solitary, the reality that Kaczynski can possess such appreciation for the living world and also a lethal sense of entitlement over the lives of others remains by the film’s end beyond grasp. The code is yet to be cracked. Benning preserves his distance from Kaczynski. The three lives claimed by the Unabomber are eulogized in the end credits, and it is made explicit that his texts are “used without permission.”

Stemple Pass (2012, 121 minutes, DCP) by James Benning was presented by Austin Film Society as part of Land and People: Recent Films of James Benning (April 6 – 8, 2013) with the filmmaker in person, curated by Richard Linklater, AFS Artistic Director.