Yinka Shonibare, The Swing (after Fragonard) © 2012 Yinka Shonibare. Courtesy of the artist and Tate Collection, London

The Progress of Love at the Menil Collection is an ambitious group exhibition that takes on the broad topics of love and African contemporary art with simultaneous exhibitions at the Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos and the Pulitzer Foundation for the Arts, St. Louis. In the Houston edition at the Menil, the concept of love that emerges is loose, multi-faceted and mostly removed from the gooey, explicitly romantic depictions that saturate popular culture. In her selection of work by primarily African contemporary artists, co-curator Kristina Van Dyke explores love’s universal, human characteristics without disregarding how these characteristics take on very culture-specific representations and expressions. Refreshingly thematic as opposed to solely geographically- or ethnically-based, the exhibition also includes work by non-African artists. The scope and variety of work is a little overwhelming.

The Progress of Love (installation view), The Menil Collection, December 2, 2012 – March 17, 2013. Photo: Paul Hester

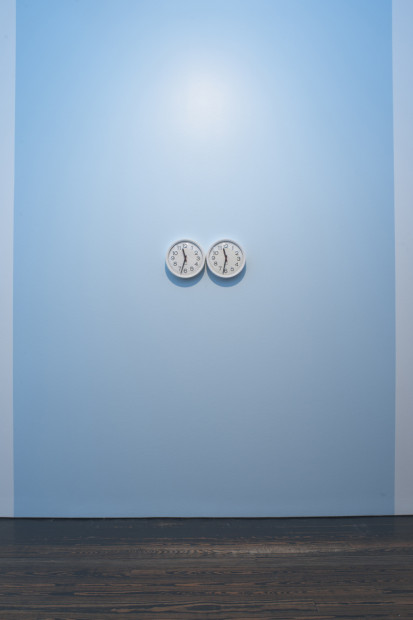

Works throughout make reference to mirroring, doubling, reflection and empathy. The introductory piece is Félix Gonzélez-Torres’ iconic Perfect Lovers, consisting of two nondescript, institutional looking clocks (think hospital or school) hung side-by-side on a wall painted a vertical band of baby blue. The clocks are set to the exact same time at the beginning of the exhibition, and throughout the remainder of the show they slowly fall out of sync. Done when Torres lost his partner to AIDS, Perfect Lovers elegiacally suggests the impossibility of a “perfect” love or union. Lovers, friends and family members may try to become one through shared experience and emotion, but true empathy may be an ability to relate to another individual’s experience without losing sight of the fact that it can never be fully lived or felt.

Odile and Odette (2005), a simple and poignant video by Yinka Shonibare, MBE, appears later in the exhibition. It elaborates on this theme of mirroring and doubling by complicating it with issues of race, cultural history and representation. Two ballerinas (one white, one black) in Dutch wax fabric stand on opposite sides of a golden frame to give the illusion of a mirror. They dance a part from “Swan Lake” normally performed by one dancer and mimic each other’s movements as precisely and synchronized as possible. The camera shifts from different vantage points and perspectives, changing who is a mirror of whom as each dancer takes a turn breaking the mirror’s frame. In the context of the exhibition, the video looks at how race plays into romantic representations (good being white, black being evil). Perfect synchronicity is at once harmonious and undesirable for how it erases individuality.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806), The Happy Accidents of the Swing, 1767-1768

oil on canvas, 81 × 64 cm (31.9 × 25.2 in), Wallace Collection, London

The exhibition’s title, The Progress of Love, alludes to another of Shonibare’s works in the show, The Swing (after Fragonard) (2001). In this sculpture, a headless mannequin is dressed in Dutch wax fabric, kicking off a shoe in a flirtatious act. The scene is recreated from one of the paintings in Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s larger painting cycle, The Progress of Love (1771-72) that depicts the stages of courtship from the chase to attainment in a flowery, Rococo style. How can love “progress” or “advance?” Much of the work in the exhibition does not necessarily imply a linear sense of progression or stages, but instead explores how the expressions and conditions under which love is felt adapt to new technological and political systems. Love can rapidly span distance with the Internet, etc., but it lives under the constant threat of disconnection or dissolution. In much of the work in the exhibition, love is fleeting, fragmentary, fragile, intermingled with violence and problematic as it crosses the dividing boundaries of race and place.

Dineo Seshee Bopape’s three-screen video projection abstractly hints at these realities of distance, fragmentation and disconnection. The video’s meandering title, they act as lovers: microwave cosmic background: so massive- that its decay opened the ultimate hole from which the universe emerged: effect no.55:2, fits the cacophonous visual mixture of disorienting image and sound. Imagine Hallmark card imagery on speed as roses, sunsets, seascapes, cloudy skies and other signifiers of the grandiosity of romantic love are filtered through stock computer image filters and animations. Images spin, scroll, overlap and peel away. Sometimes interrupting, flashing text says, “RENDER!”—a reminder that this is after all just the byproduct of churning hardware, analogous to our own uncontrollable mental hardware as images might pop in and out of our brains. A soundtrack of garbled sounds, like the disconnect signal on a phone, and snippets of soul ballads fade in and out like things heard half-awake. It is a very difficult piece to actually sit through because of its lack of narrative and resolution. Its layers seem to tear apart sublimity and romantic bliss in favor of rough cuts and interruptions.

The Progress of Love (installation view), The Menil Collection, December 2, 2012 – March 17, 2013. Photo: Paul Hester

While Bopape’s video is not a culturally specific statement, other works in the exhibition require more decoding to understand the specific cultural references. Zoulikha Bouabdellah’s Chéri (2007) covers an entire gallery wall with a grid of sheets of paper each with an individual word for love in Arabic written in red lacquer. To me, they simply look like abstract calligraphy, but with the background information in mind they acknowledge the existence of different cultural vocabularies of love. Like the old anecdote about Inuit languages having hundreds of words for snow to explain language and perception, Chéri brings up the question: Could some cultures be more attuned to the nuances of love?

The Progress of Love (installation view), The Menil Collection, December 2, 2012 – March 17, 2013. Photo: Paul Hester

Eaten by the Heart, a commissioned video by Zina Saro-Wiwa, also takes on the topic of the cultural expression or performance of love. According to Saro-Wiwa, kissing divides the East and West because in Africa it is not as common a public act and rarely seen in film or popular visual culture. Saro-Wiwa started her project by interviewing volunteers from Africa or the African diaspora to talk about heartbreak and love. She then asked these interviewees if they would participate in a kissing performance. The willing participants voluntarily paired themselves up with other participants for Saro-Wiwa to film them. The resulting video features these partners kissing against a bright, monochromatic backdrop. Watching the prolonged kissing is uncomfortable, and it made me think about the aesthetics of the manufactured Hollywood kiss. Real people kissing, shown unflinchingly up close, are not so pretty. Appropriate to the Eaten by the Heart title, the sucking and biting mouths take on a sinister look of lovers consuming one another.

The Progress of Love (installation view), The Menil Collection, December 2, 2012 – March 17, 2013. Photo: Paul Hester

Another standout work, commissioned by the Menil, A Lagos State of Mind (2012) by Emeka Ogboh, evocatively plops the viewer into Lagos, Nigeria using sound and a prop. It features a bright yellow VW minibus called a danfo and common to Lagos. Surrounding the van are two speakers piping in recordings of the streets in Lagos, and viewers can sit inside the van to listen on headphones snippets from a call-in radio show where locals describe what they are looking for in a significant other or discuss relationship issues. The audio sounds like it was recorded from an actual van in Lagos as you can hear the sounds of bumps in the road and traffic noise. The descriptions of an ideal partner are similar to what you might find in an online dating profile, and it captures in a very direct way the experience of finding love and maintaining a relationship.

The Progress of Love (installation view), The Menil Collection, December 2, 2012 – March 17, 2013. Photo: Paul Hester

Other works do not explore notions of romantic love, but the love that could be associated with ethnic solidarity. In Romuald Hazoumé’s video ONG SBOP (2012), famous African musicians carry around motor oil cartons with the name of a fake NGO (“NGO SBOP: Beninese Solidarity with Endangered Westerners”). The celebrities approach people in Benin on the street, in cars and vendors in markets to ask for a small donation to help white people. The shocked reactions of the people are often provocative, touching and humorous. Many people who can least afford to give, drop a coin in the container anyway. Whether they simply do not want to disappoint the celebrity and the camera would be tricky to know, but the murkiness of their intentions works in the context of a video that questions the impulse behind charity and how a gesture of “love” can also be a form of condescension. For example, as one man donates, he sarcastically and insightfully says, “because we often need someone smaller than we are.” Other people appear genuinely shocked at the idea that there can be poor westerners, but they all seem to agree with the argument that westerners don’t love their neighbors the way Africans do, conforming to a stereotype of westerners as unscrupulous individualists with little social conscience.

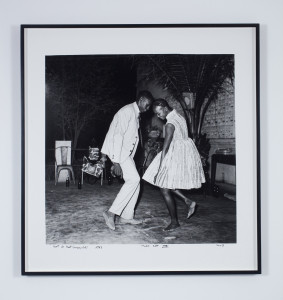

Malick Sidibé, Nuit de Nöel (Happy Club) (1963),

courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, NY

Outside of these major pieces and commissions are a constellation of photographs, paintings, drawings and sculptures. Many of these works effectively fit into the exhibition, but they do not necessarily have the experiential power and presence of some of the work discussed that more directly embodies the exhibition’s major themes. Perhaps just as much could have been said with less, but I admire the ambition of tackling such a slippery subject. Love is a word popping up in more and more exhibition titles with shows on view at ICA Boston and Ackland Art Museum. I wish I could see these shows to compare and contrast, but based on the descriptions online, love is framed as a political force and a sociological category for analysis where different representations and rituals can be studied. With Progress of Love as a kind of general survey, I can imagine a “Progress of Love Part 2” that limits itself to work about one or two facets of the show. I found myself gravitating to work that was more about the experience of love than work that seemed more tangentially related to the malleable theme. Some sculpture was more diagrammatic or illustrative of a concept or statement about love. For example, Kendell Geers’ Ritual Slip (2010) series with words like “love” or “hate” beaded onto traditional aprons required too many layers to sort through to understand the work’s meaning. Joel Andrianomearisoa’s Boys Cake (2010) sculpture referenced homosexuality through pornographic images, but I could not understand why they were in the form of compressed bricks and unsure of the larger statement. Works like these left me wondering: Maybe a show on love should you make you feel before you think?

1 comment

I saw this show at the end of December I believe and just fell in love with the work and layout of the spaces.