These days, signs are not to be trusted. Their meaning, as Derrida argued, is not immediately clear to us. What they refer to is absent, so the meaning they once presented is absent as well. Meaning is moving along a chain of signifiers and one is never sure of its exact location. Long gone are the days when word, object and thought dissolved into the soothing communion wafer of meaning.

Upon entering Robert Hodge’s current show, Living in the Past is My Future at the South Dallas Cultural Center, one is willfully greeted by an “artificial nigger.” Well, in all fairness, what the visitor is greeted by is a signpost of another’s imagination. This wild caricature, dictated from a psyche that necessitated such an apparition, reflected the inventor’s own fears and desires. Forged in slavery, tempered by the 19th century machinery of mass production and popular culture, invested with purposeful cruelty, “this marker of limits” became the penultimate American scapegoat. The civil rights movement, the black empowerment movement, sweeping civil rights legislation and a general inclusive embrace of democracy have all eroded America’s racial hierarchy and the residue left from slavery, through Jim Crow into today’s institutional racism. Yet this bugbear remains. So the declination of the concept, artificial or real, is left up to the individual. One has to know on which side they like their bread buttered.

Not necessary to me.

For Hodge, this totem is only necessary as a disclaimer. The narratives he finds compelling are those that highlight and reaffirm the African’s story in his quest for his very own version of America. Plain and simple, this body of work is about cultural retention and reflection. It is a 21st century “Color Me Brown” that speaks of things long obscured or relegated to February cruises. I grew up with a(n original in a non-stop flash) “Color Me Brown” coloring book, Carter G. Woodson and Lerone Bennett history books, stories told on the porch that augmented the histories I studied in school. But more importantly, with two parents that possessed upper-level degrees. Black American history was every day. I learned early on, the culture is in the language. Not the case for many kids today.

Hodge’s Pop Quiz series, silk screens of both text and portraits, is homage to those great human beings that far too often have been confined to the most misspelled and unstable month on the calendar. There is also an interesting dichotomy going on between the visual and the spoken, between the historian and the griot. I couldn’t help but think how to employ Charles White’s “Cat Cradle” in this exercise, draping string between pieces; speaking of the sticky correspondence between seeing and actually knowing. To a larger extent I think that is one of the points that Hodge is presenting.

Navigation into black art is usually viewed as a tricky endeavor, kind of like really getting to know and dealing with black people. The pop quiz I envisioned dealt with African American masters and defining pieces from their oeuvres. The Alstons, the Catletts, the Overstreets, the Chase-Ribouds, the Chandlers, the Mailou Jones, the Haydens, the Hughie Lees. Then parade art teachers, curators, writers, gallery owners and collectors through “the quiz.” See how many correct answers are rendered, how many first introductions are issued, how many esoteric recalibrations of surprise and wonder bubble up. The “high noon” that Malcolm talked about on Sunday morning still shines brighter than it should during the rest of the week in the art world.

That he stands on the ash heap of ancestors who have inspired and guided is obvious. Hodge implements this by highlighting their relevance, many times, within the scope of his larger pieces. Right under the viewer’s nose one might find an allusion to a Charles Criner or a deconstructed Harvey Johnson, or perhaps remnants of a truncated Bert Long. He understands the machinery that is essential to the telling of artist’s story. He understands that we all will be traveling that way. Nice to have someone from home to tell your stories.

“You take home with you everywhere you go,” James Baldwin said, “you better, or you will be homeless.” Uh-oh, that afro-futurism thing again. How you schlep home with it is as essential as what you carry of it. Do you tote it in a rhyme, map it out in tats or piercings? Sometimes it’s the swag in your roll, the part in your coif or the way the naps in your Tuff Gong fluff up under your chinny chin chin.

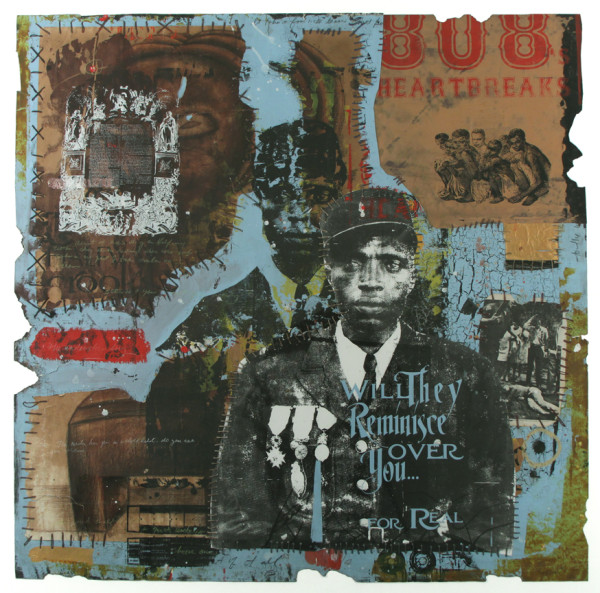

Music has always informed his work. Hodge employs lyrics, hooks and mantras from the hip-hop vocabulary to ground and expand the palette of his collages. In Will They Reminisce Over You, Hodge presents an exercise in hard-edge sentimentality. Little-known histories, forgotten promises, daily mantras, lost rhymes are framed under a classic Pete Rock and CL Smooth tune about loss and vulnerability. To bolster his claim, he stamps “808” and “Heartbreak” throughout the collage, referencing Kanye West’s album of the same name. He parallels the loneliness, heartache and introspection with patchwork stitching that piece the collective unconscious along the frayed edges of the personal.

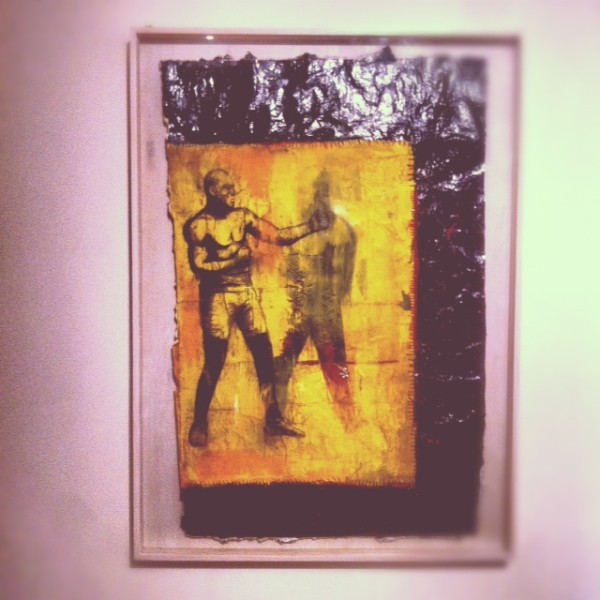

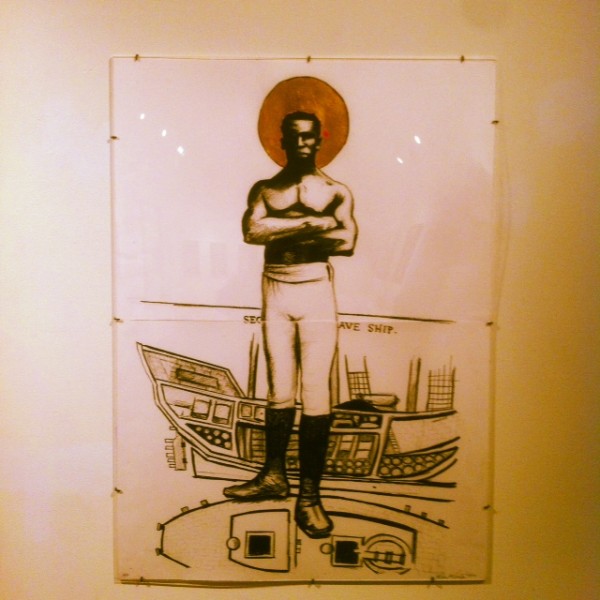

Violence and suffering have been a part of the African’s experience in America since day one. Cribbing the title from Jean-Michel Basquiat’s caveat, in Kings Often Get Their Heads Cut Off Hodge lays out a roll call of fallen princes. They are presented topsy turvy on the textured paper of promotional posters, which speaks of their grassroot beginnings, their fragility, their grit. Some are of the struggle, others of the boogie, many innocent bystanders, but all victims of an attenuated lifespan that causes reflection and countless “what if”s. Erykah’s ‘Twinkle” propels them forward, leaving the living with full responsibility for their memories and principles.

In Whose Country is This, one is witness to the solipsism of the West exuded by these “solid citizens,” feigning entitlement and privilege in the face of growing browning of the landscape. A torn Western Union telegram pasted across the top seems to speak of another time, an exclusive importance. In different times it announced an important event—the birth of a child, the death of a soldier; now it is used for sending money. It is an archaic remnant that whispers the end of a moribund civilization. Are these conquerors to be admired, pitied or despised huddled at the bus stop? The genuflected and benighted first American at the edge of this composition offers a karmic answer.

The slippage of the “artificial nigger” has been in place since its inception. Hodge furthers this erasure by revealing another chain in the link of signifiers. This long forgotten signpost, draped with a green handkerchief, signaled to runaway slaves that this was a “safehouse,” indeed, the direction of freedom. While it is obvious that neither Nelson Head nor his grandfather are confirming this in their assessment of this peculiar totem, the fact that Mr. Head realizes and acknowledges that there are not enough “signposts” to go around is significant. It is a clarion signal that the immobile star that has guided their lives for centuries has moved, forever.

Hodge presents an unflinching concerto to a people on whose shoulders he stands, to those lost and to the changing landscape we face. But more than anything, this exhibition raises its hand in the long twilight struggle of re-appropriation of a signpost, both the signifier and the signified. The realignment of this signpost has ALWAYS gone on, like a Lucille Clifton poem, but in the more recent past it was redefined in Dick Gregory’s promise to his mother, moved through Richard Pryor’s diffusive attempt through humor. The gauntlet has now been taken up by hip-hop culture’s organic, unstable and implacable assertion that this time, we are going to define the depths and parameters of that sign, and no one else. Very much necessary for the healing of America and the planet. Both of which are very much necessary to me.

Feel free to insert your own marginalia.

An African American male is standing in front of a hardware store looking at a group of dancing artificial Santas.

Brother: Nice.

A car pulls up. Horn honks. He turns to find himself face-to-face with the real Santa.

Santa: Get in!

Brother: Santa?!

They speed off, weaving in and out of traffic. Like Willie D, Santa is driftin’ while he drives.

Santa (a bit perturbed): What the ho ho heck were you thinking? Imagine if I bought a mechanical you for my lawn. It’s creepy, right?

Brother (looking rather ManTannish): Creepy? Yeah that would be creepy, that would be real creepy…

Santa: Try buying something that would bring you years of happiness. Okay, you’re back on my nice list.

Car fishtails back to the exact spot where all this began. Brother gets out.

Listen to the voice of reason, the narrator extols. Luxury intelligently priced.

Robert Hodge: Living in the Past is My Future is on view until January 26, 2013.